Person sitting alone at home with a phone on the table

Combating Social Isolation: Strategies, Impacts, and Community Initiatives

Social isolation refers to a state where an individual has minimal contact with others, often leading to prolonged loneliness and lack of social interactions that are fundamental to human well-being. This phenomenon has become increasingly relevant in today's digital age where face-to-face interactions are often substituted with online communications that may lack the depth and emotional resonance of in-person connection. The term describes an objective condition—a measurable deficit in social contact and community participation—rather than merely a feeling, though the subjective experience of loneliness often accompanies and compounds the effects of isolation.

The relevance of social isolation in contemporary society cannot be overstated. Modern life has undergone profound transformations that affect how humans connect with one another. Urbanization has created densely populated cities where neighbors rarely know each other's names. The decline of traditional community institutions—religious congregations, civic organizations, neighborhood associations—has eliminated many of the structures that once brought people together regularly. Work patterns have shifted toward remote employment, gig economy arrangements, and schedules that make coordinating social activities increasingly difficult. Family structures have changed, with more people living alone than at any previous point in history and extended family networks often scattered across great distances.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated this issue, forcing many into physical isolation and highlighting the critical nature of this social issue in ways that touched virtually every person on the planet. Lockdowns, social distancing requirements, and the closure of gathering places brought the experience of isolation to populations who had never previously experienced it, while dramatically worsening conditions for those already isolated. The pandemic served as a massive, unplanned experiment in what happens when human beings are deprived of regular social contact, and the results confirmed what researchers had long suspected: social connection is not a luxury but a fundamental human need, as essential to health as nutrition, sleep, and physical activity. For more insights into the definition and growing importance of addressing social isolation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a detailed overview of the public health dimensions of this phenomenon.

Brief Overview of the Consequences of Social Isolation on Mental and Physical Health

The impact of social isolation extends far beyond mere loneliness, reaching into virtually every dimension of human health and functioning. It significantly affects both mental and physical health in ways that are now well-documented through decades of research across multiple disciplines. The evidence has become so compelling that many public health authorities now consider social isolation a risk factor comparable to smoking, obesity, or physical inactivity in its capacity to shorten lives and diminish quality of life.

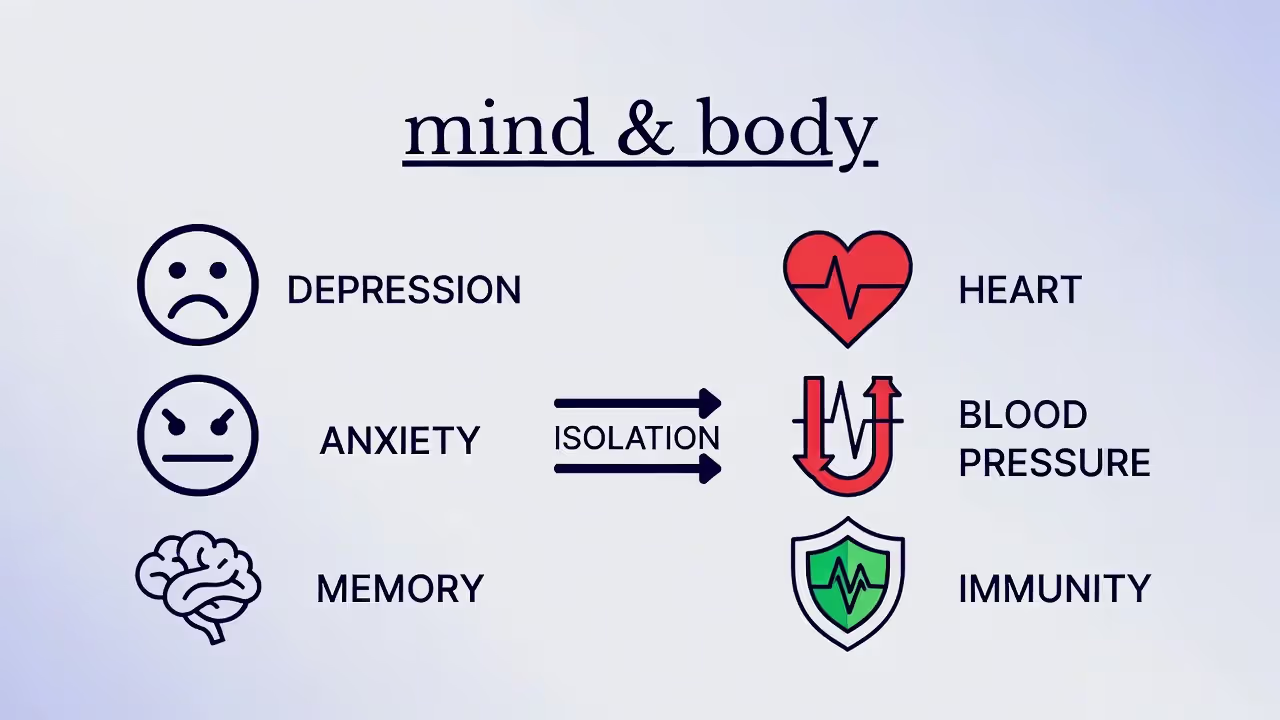

Mentally, social isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. The mechanisms are both psychological and neurobiological. Human brains evolved in the context of social groups, and they require regular social input to function optimally. When deprived of this input, the brain responds with stress hormones, inflammatory processes, and changes in neural functioning that predispose individuals to mental health disorders. Depression in isolated individuals may arise from the absence of positive social reinforcement, the loss of meaning and purpose that relationships provide, and the neurochemical changes associated with chronic stress. Anxiety often develops as isolated individuals lose confidence in their social skills and begin to perceive social situations as threatening rather than rewarding.

Physically, social isolation has been linked to a higher risk of conditions such as heart disease, high blood pressure, and a weakened immune system. The pathways connecting isolation to physical disease involve multiple mechanisms. Chronic loneliness elevates cortisol and other stress hormones, which over time damage cardiovascular tissue, suppress immune function, and promote inflammation throughout the body. Isolated individuals also tend to engage in fewer healthy behaviors—they exercise less, eat less nutritiously, sleep more poorly, and are more likely to use alcohol or other substances to cope with their distress. The cumulative effect of these psychological and behavioral factors produces measurable increases in morbidity and mortality. These health impacts are well-documented in a comprehensive review by Harvard Health Publishing, which synthesizes evidence from epidemiological studies spanning decades and multiple countries.

Introduction of the Purpose of the Article: To Provide Strategies to Prevent Social Isolation

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

This article aims to address the critical and growing issue of social isolation by offering effective strategies to prevent it before it takes hold and to remediate it when it has already developed. Through understanding its causes and consequences, and by implementing community-focused and individual-based interventions, we can mitigate the risks associated with social isolation and create conditions that foster the human connection essential to flourishing. This approach not only enhances individual well-being but also strengthens community bonds, creates more resilient social networks, and ultimately contributes to healthier, more vibrant societies.

The prevention of social isolation requires action at multiple levels—from individual choices about how to spend time and maintain relationships, through community initiatives that create opportunities for connection, to policy decisions that shape the built environment and social infrastructure within which people live. No single strategy is sufficient; rather, a comprehensive approach that addresses the multiple causes and manifestations of isolation offers the best hope for meaningful impact. This article will explore strategies across all these levels, providing both conceptual frameworks for understanding the problem and practical guidance for addressing it. To explore more about the preventive measures, the World Health Organization (WHO) offers resources and guidelines on how social determinants can be managed to foster better health outcomes and more connected communities.

Understanding Social Isolation

Explanation of the Difference Between Social Isolation and Loneliness

Social isolation and loneliness, while often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, are distinct concepts that require different approaches to address effectively. Social isolation is an objective measure referring to the lack of social connections or infrequent social contact with others—it can be quantified by counting relationships, measuring frequency of interactions, or assessing participation in community activities. Loneliness, in contrast, is a subjective feeling of being alone or separated, regardless of the amount of social contact. It reflects the gap between the social connection a person desires and what they actually experience.

This distinction matters enormously for intervention. A person can be socially isolated—have few contacts and rarely interact with others—yet not feel particularly lonely if they are content with solitude and their social needs are modest. Conversely, and perhaps more commonly, a person can be surrounded by others, have extensive social networks, and participate actively in community life yet still experience profound loneliness because their relationships lack the depth, intimacy, or quality they crave. Loneliness can occur in the presence of others if the relationships are not meaningful, if they involve roles rather than genuine connection, or if the person feels misunderstood or unseen despite being physically present with others.

Loneliness is not about being alone—it's about feeling alone. A person surrounded by people but lacking meaningful connection experiences loneliness just as acutely as someone in physical isolation. The cure for each may look quite different.

— Dr. John Cacioppo

Understanding these differences is crucial for addressing each issue effectively. Interventions that simply increase social contact may help the isolated person who is lonely for lack of opportunity to connect but will likely fail for the person whose loneliness stems from relationship quality issues. The latter may need help developing social skills, processing past relational trauma, or finding communities where they feel genuinely accepted and understood. The National Institute on Aging provides further explanations on how these conditions impact health differently and require tailored approaches.

Identification of the Causes of Social Isolation

Social isolation can be caused by a myriad of factors, often interacting in complex ways that compound their individual effects. Understanding these causes is essential for developing targeted interventions that address the specific barriers to connection that different individuals face.

Age: Older adults often face social isolation due to multiple age-related factors that accumulate over time. The loss of friends and family to death reduces social networks naturally, and these losses become more frequent as one ages. Retirement removes the daily social contact that work provided, and many people find that relationships with former colleagues fade quickly when they no longer share the common ground of workplace experience. Declining mobility limits the ability to visit others or participate in activities outside the home. Health conditions may make communication difficult—hearing loss, cognitive decline, or chronic pain can all interfere with social interaction. For many older adults, these factors combine to create a progressive narrowing of social worlds that can be difficult to reverse.

Disability: Physical, sensory, or intellectual disabilities can hinder one's ability to engage in social activities in multiple ways. Physical barriers may prevent access to social venues that lack appropriate accommodations. Communication disabilities may make interaction difficult or exhausting. Cognitive disabilities may affect social comprehension and the ability to maintain relationships. Beyond these direct effects, disability often carries social stigma that leads others to avoid or exclude disabled individuals, and the experience of stigma may cause disabled people themselves to withdraw from social situations where they anticipate rejection or discomfort.

Technology: The relationship between technology and social isolation is complex and paradoxical. While digital communication tools offer unprecedented ability to maintain relationships across distances, over-reliance on digital communication can reduce face-to-face interactions that provide richer emotional connection. Social media may create an illusion of connection while actually fostering comparison, envy, and a sense of inadequacy. The constant availability of digital entertainment and information may crowd out time that might otherwise be spent in social activity. For some populations—particularly older adults who did not grow up with these technologies—digital tools may be inaccessible or intimidating, excluding them from increasingly online social networks.

Geographic Location: Individuals in rural or remote areas may have limited access to social venues, community organizations, and potential social contacts simply due to physical distance and sparse population. Transportation challenges compound this issue—without reliable transportation, even social opportunities that exist may be unreachable. Rural communities also tend to experience greater outmigration of younger people, leaving behind aging populations with shrinking social networks.

Cultural Factors: Language barriers can profoundly isolate immigrants and others who do not share the dominant language of their community. Cultural stigmas around mental health, disability, or certain life circumstances may prevent people from seeking connection or support. Discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or other characteristics can exclude individuals from social opportunities and create hostile environments that discourage participation in community life.

Each of these causes affects individuals differently based on their specific circumstances, resources, and vulnerabilities, making it essential to address them through targeted interventions that recognize this diversity.

Discussion of the Populations Most at Risk of Social Isolation

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Certain populations are more vulnerable to social isolation due to the accumulation of risk factors and the particular challenges they face in maintaining social connection. Recognizing these high-risk groups enables more effective targeting of prevention and intervention efforts.

Senior Citizens: As mentioned, the elderly are particularly susceptible due to various age-related changes and life events. The statistics are sobering: approximately one-quarter of adults aged 65 and older are considered socially isolated, and the proportion increases with advancing age. Among those over 85, isolation becomes the norm rather than the exception. The consequences for this population are particularly severe, as social isolation in older adults is associated with approximately 50% increased risk of dementia, 29% increased risk of heart disease, and 32% increased risk of stroke.

Immigrants and Refugees: These groups may struggle with language barriers and cultural integration, isolating them within their new communities even when they are physically present. The loss of their original social networks—often permanently—compounds the difficulty of building new ones in unfamiliar cultural contexts. Discrimination, legal status concerns, and the psychological burden of displacement further complicate their ability to form new connections.

People with Disabilities: Accessibility issues and societal stigma can limit their opportunities for social interaction. The built environment often excludes people with mobility impairments, while social environments may be unwelcoming to those with cognitive or developmental disabilities. Many disabled individuals report that the social barriers to connection—others' discomfort, assumptions of incompetence, or simple failure to include them—are more isolating than the physical limitations of their conditions.

Rural Residents: Those living in geographically isolated areas might have fewer opportunities to engage with communities simply because there are fewer people nearby and greater distances to travel. The decline of rural institutions—churches, schools, local businesses—has further reduced the gathering places where rural residents once connected.

Social isolation is not distributed randomly through the population—it clusters among those who already face multiple disadvantages. Addressing isolation requires addressing the structural factors that create and maintain inequality in access to social connection.

— Dr. Julianne Holt-Lunstad

Organizations like the World Health Organization emphasize the importance of addressing these risks through inclusive social policies and community planning to reduce the prevalence of social isolation across these groups, recognizing that effective prevention requires systematic attention to the structural factors that create vulnerability.

The Impact of Social Isolation

Review of the Psychological Effects

Social isolation can lead to a range of psychological effects that detrimentally impact an individual's mental health, often in ways that become self-reinforcing and increasingly difficult to reverse over time. The human brain is fundamentally a social organ—it evolved in the context of social groups and requires regular social input to maintain healthy functioning. When deprived of this input, multiple psychological systems begin to malfunction.

Depression: Isolation can contribute to feelings of sadness and hopelessness, exacerbating or leading to clinical depression. The mechanisms are both psychological and neurobiological. Psychologically, social connection provides much of the meaning, purpose, and positive reinforcement that sustains well-being; without it, life can seem empty and pointless. Neurobiologically, isolation alters the functioning of neurotransmitter systems involved in mood regulation, particularly serotonin and dopamine pathways. Isolated individuals show patterns of brain activity similar to those seen in clinical depression, even before depressive symptoms become apparent. Once depression develops, it further reduces motivation and energy for social activity, creating a vicious cycle that deepens both isolation and depression.

Anxiety: The lack of social interaction can cause increased levels of stress and anxiety through multiple pathways. Without regular practice, social skills atrophy, and individuals may lose confidence in their ability to navigate social situations successfully. This loss of confidence leads to anticipatory anxiety about social encounters, which may cause avoidance that further reduces skills and confidence. Isolation also eliminates the social buffering effect that relationships provide against life stressors—isolated individuals must cope with challenges alone, without the practical help, emotional support, or perspective that others can offer. Additionally, the hypervigilance toward social threats that develops in lonely individuals—an evolutionary adaptation designed to protect against exclusion from the group—can manifest as chronic anxiety in modern contexts.

Low Self-Esteem: Being isolated can lead to negative self-perception and low self-worth as social interactions often play a key role in validating self-esteem. Humans rely heavily on reflected appraisals—we understand ourselves partly through how others respond to us. Without this feedback, or with predominantly negative feedback from limited interactions, self-concept suffers. Isolated individuals often begin to believe that their isolation reflects something fundamentally wrong with them, that they are unlikeable or unworthy of connection, and these beliefs further undermine the confidence needed to reach out and form new relationships.

Research from the American Psychological Association provides extensive insights into how social isolation can drive these psychological disorders, documenting both the epidemiological associations between isolation and mental illness and the neurobiological mechanisms that explain these relationships.

Examination of the Physical Health Impacts

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

The physical health impacts of social isolation are significant, well-documented, and increasingly recognized as major public health concerns comparable to traditional risk factors like smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. The evidence has accumulated across hundreds of studies involving millions of participants, and the consistency of findings across different populations, methodologies, and time periods provides strong confidence in the causal relationship between isolation and disease.

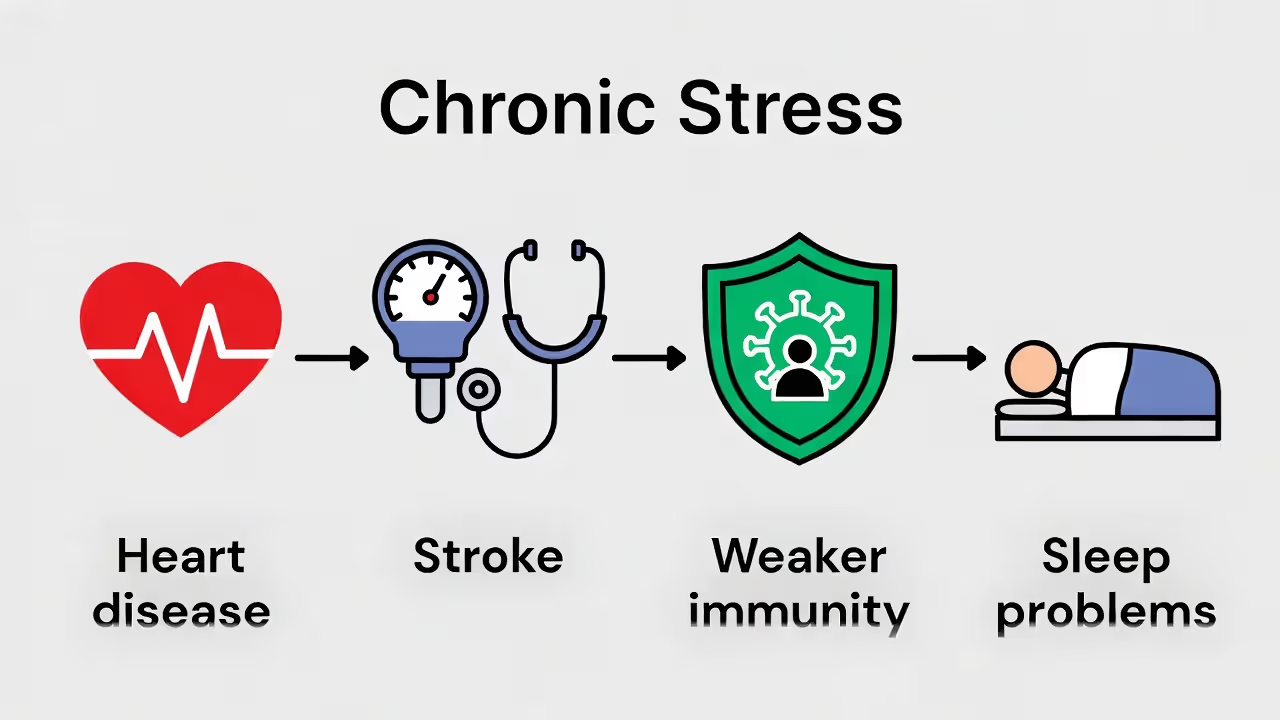

Increased Risk of Heart Disease: Lack of social relationships has been linked to increased risks of cardiovascular diseases through multiple mechanisms. Chronic loneliness activates the body's stress response systems, leading to sustained elevations in cortisol and other stress hormones that damage blood vessel walls, promote arterial plaque formation, and increase blood pressure. Isolation also promotes unhealthy behaviors—isolated individuals are more likely to smoke, less likely to exercise, and more likely to consume unhealthy diets—that independently increase cardiovascular risk. The inflammation associated with chronic stress further contributes to heart disease development.

Stroke: Isolation has been associated with higher rates of stroke due to the same stress-related mechanisms that promote heart disease, combined with reduced physical activity that often accompanies withdrawal from social life. The risk elevation is substantial—socially isolated individuals experience approximately 32% higher stroke risk compared to those with robust social connections, a risk increase comparable to that associated with traditional risk factors.

Other Health Issues: Including sleep disturbances that are nearly universal among lonely individuals and that independently contribute to disease risk; altered immune functions that increase susceptibility to infections and may accelerate cancer progression; and more severe symptoms of existing illnesses, as isolation impairs the body's ability to heal and recover. The mechanisms connecting isolation to immune function are particularly well-documented—lonely individuals show elevated inflammatory markers, reduced response to vaccines, and impaired wound healing compared to their connected peers.

The Harvard Medical School discusses how isolation not only exacerbates existing conditions but also may lead to the development of new health issues, creating a cascade of declining health that can become difficult to interrupt without addressing the underlying social deficits.

Social and Economic Consequences

Social isolation also has broader social and economic impacts that extend beyond the affected individuals to impose costs on communities, employers, and society at large. These collective consequences provide additional rationale for public investment in prevention and intervention efforts.

Reduced Workforce Participation: Individuals who are socially isolated are less likely to participate actively in the workforce due to mental or physical health issues, leading to reduced economic productivity. Depression and anxiety associated with isolation impair cognitive function, reduce motivation, and increase absenteeism. Physical health problems lead to disability and early retirement. The loss of human capital represented by isolated individuals who are unable to work fully represents a significant economic burden—some estimates suggest that loneliness costs employers billions of dollars annually in lost productivity, and economies suffer from the reduced contributions of isolated workers.

Increased Healthcare Costs: The health deteriorations associated with isolation increase healthcare demands and costs substantially. More frequent hospital visits, increased reliance on emergency services, longer hospital stays, and greater need for chronic disease management all strain public health resources. Isolated older adults are more likely to be admitted to nursing homes, at enormous cost to individuals, families, and public programs. Mental health treatment costs escalate as isolation-driven depression and anxiety require professional intervention.

Detailed analysis by The Brookings Institution explores how social isolation affects economic growth and healthcare systems, highlighting the importance of strategic interventions to counteract these impacts and demonstrating that investment in social connection programs often yields positive returns through reduced healthcare costs and increased economic participation.

Recognizing Signs of Social Isolation

How to Identify Someone Suffering from Social Isolation

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Identifying someone who is suffering from social isolation involves noticing changes in their behavior and lifestyle that indicate they are withdrawing from social contact. Early identification enables intervention before isolation becomes entrenched and its consequences become severe. Those who are positioned to observe these changes—family members, friends, neighbors, healthcare providers, and community members—play crucial roles in recognizing and responding to isolation.

Reduced Social Interactions: Noticeable decreases in communication or participation in social activities often provide the first signs that someone is becoming isolated. This might manifest as declining invitations that were previously accepted, withdrawing from regular gatherings or activities, reducing phone or text communication, or spending increasing amounts of time alone. The change is often gradual and may be easy to overlook, particularly if the person provides plausible excuses or if others are absorbed in their own busy lives.

Neglect of Personal Hygiene or Responsibilities: Lack of attention to personal care or household chores might suggest a lack of motivation or interest that often accompanies isolation. Without the anticipated social contact that motivates grooming and home maintenance, isolated individuals may let these standards slip. Declining self-care can also reflect the depression that often develops alongside isolation.

Withdrawal from Usual Activities: Absence from clubs, work, or hobbies that were previously important suggests that something has changed in the person's engagement with life. When someone stops attending their book club, quits their volunteer position, or abandons a lifelong hobby, these changes warrant attention and inquiry.

Organizations like the Mental Health Foundation provide guidelines on identifying these signs in others and offering support in ways that are helpful rather than intrusive or judgmental.

Early Warning Signs and Symptoms to Look Out for in Oneself and Others

Being aware of early warning signs in oneself or others can help prevent the deeper issues associated with prolonged isolation. These signs often precede obvious behavioral changes and may be visible primarily through conversation and emotional expression.

Persistent Feelings of Loneliness or Sadness: Feeling disconnected and lonely even when occasional interactions occur suggests that current social contacts are not meeting the person's needs for connection. This may indicate that relationships lack depth, that the person feels misunderstood or unseen, or that something is preventing genuine connection even when contact occurs.

Expressing Feelings of Worthlessness: Conversations where individuals express that they feel they do not matter or are a burden to others reflect the self-esteem erosion that accompanies isolation. These expressions should be taken seriously as both signs of current distress and risk factors for deepening isolation.

Change in Sleep Patterns: Excessive sleep or insomnia could be a sign of emotional distress related to isolation. Sleep disturbances are nearly universal among lonely individuals and both cause and result from the depression that often accompanies withdrawal from social life.

Loss of Interest in Personal Hobbies: Lack of enthusiasm towards previously enjoyed activities suggests a broader disengagement from life that isolation often produces. Hobbies often have social components—even solitary activities may be discussed with others or shared through communities of interest—and their abandonment may reflect retreating connection.

Early recognition of these signs is crucial for timely intervention, which can mitigate the adverse effects of social isolation before they become severe or self-reinforcing. Resources such as Psychology Today offer further reading on understanding and managing these symptoms effectively, providing guidance for both those experiencing isolation and those seeking to help.

By understanding and recognizing these signs early, individuals and communities can take proactive steps to reach out and reconnect, providing necessary support to those who may be drifting into social isolation before the drift becomes a plunge.

Strategies to Prevent Social Isolation

Community Engagement: Importance of Building Strong Community Networks

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Building strong community networks is essential in combating social isolation, providing the social infrastructure within which individuals can find connection, support, and belonging. These networks provide a supportive social structure that can enhance individual well-being and foster a sense of belonging that protects against isolation even during difficult life transitions or challenging circumstances. When strong community networks exist, individuals who experience life changes that might otherwise lead to isolation—retirement, widowhood, relocation—have existing structures to catch them.

Activities such as local community events, clubs, and volunteer organizations play a crucial role in integrating individuals into the social fabric by providing regular occasions for interaction, shared activities that create common ground, and contexts within which relationships can develop naturally. These structured opportunities for connection are particularly important for individuals who may not naturally seek out social contact or who lack the confidence to initiate relationships independently. A study highlighted by the National Institute on Aging shows that older people who engage in community activities experience lower levels of loneliness and social isolation, with benefits that extend to physical health and cognitive function as well as emotional well-being.

The design of physical spaces also influences community connection. Neighborhoods with walkable streets, common gathering spaces, and mixed-use development that brings together residential, commercial, and recreational functions promote casual encounters and spontaneous social interaction. In contrast, car-dependent sprawl, gated communities, and the absence of public spaces undermine the natural processes through which community networks form and maintain themselves.

The Role of Technology in Connecting People: Pros and Cons

Technology can be a double-edged sword in the fight against social isolation, offering both powerful tools for connection and significant risks of deepening disconnection. Understanding this complexity is essential for harnessing technology's benefits while mitigating its harms.

Pros: Digital platforms and social media can connect people across distances, allowing for maintaining relationships and meeting new friends regardless of geographic separation. For those with mobility limitations, chronic illness, or caregiving responsibilities that make leaving home difficult, technology may provide the only practical means of social connection. Teleconferencing and social apps enable those who are physically unable to attend in-person gatherings to stay connected with communities of interest. Online communities can be particularly valuable for individuals with niche interests or marginalized identities who may struggle to find compatible connections locally. During the COVID-19 pandemic, technology allowed many people to maintain relationships that would otherwise have been severed entirely by physical distancing requirements.

Cons: Overreliance on digital communication can lead to superficial connections that do not replace the depth and emotional support of face-to-face interactions. Something important is lost when communication lacks the physical presence, nonverbal cues, and shared activities that characterize in-person connection. Social media may create an illusion of connection while actually fostering comparison, envy, and a sense of inadequacy as users compare their real lives to others' curated presentations. The constant availability of digital entertainment can crowd out time and motivation for real-world social activity. There's also a significant risk of exacerbating loneliness among those who may feel overwhelmed or excluded by rapidly changing technologies—particularly older adults who did not grow up with these tools and may find them confusing or alienating.

Technology is a tool, not a solution. It can facilitate connection for those who use it intentionally, but it can also substitute the illusion of connection for the real thing. The question is not whether to use technology but how to use it wisely.

— Dr. Sherry Turkle

A comprehensive look at these dynamics is presented in a study available on Pew Research Center, which examines how different demographics use technology for social connection and documents both the benefits and the risks of technology-mediated relationships.

Importance of Accessible Transportation and Mobility Aids

For many individuals, especially older adults and people with disabilities, the lack of accessible transportation is a significant barrier to social participation that no amount of willingness or motivation can overcome. You cannot attend a social gathering, visit a friend, or participate in community life if you cannot get there. Mobility aids and accessible transportation options are therefore crucial infrastructure for social connection, enabling these individuals to attend social gatherings, access community services, and engage in hobbies outside their homes.

The transportation barrier to social connection is particularly acute in suburban and rural areas where public transportation is limited or nonexistent and where distances between homes, services, and gathering places make walking or cycling impractical. In these contexts, losing the ability to drive—whether due to age, disability, or economic circumstances—can mean losing access to social life entirely. Enhancing transportation options through improved public transit, specialized services for seniors and disabled individuals, volunteer driver programs, and ride-sharing arrangements can greatly improve their ability to connect with others and participate in community life.

Research by Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives often focuses on how improving transportation infrastructure can help reduce social isolation among older adults by providing them with the means to be more socially active, documenting the relationship between transportation access and social participation across multiple studies and contexts.

By integrating these strategies—community network building, thoughtful technology use, and transportation access—communities can create environments that foster social connections and significantly reduce the risks associated with social isolation.

Initiatives and Programs

Overview of Existing Community and Government Programs Aimed at Reducing Social Isolation

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Numerous community and government initiatives have been developed to combat social isolation across various populations, particularly among the elderly, disabled, and other vulnerable groups who face the greatest barriers to connection. These programs often focus on creating opportunities for social interaction, providing support services, and enhancing accessibility to community resources. They represent accumulated wisdom about what works to address isolation, drawn from decades of experimentation and evaluation.

Government programs addressing isolation operate at multiple levels. National initiatives may fund research, develop guidelines, or support state and local efforts. State programs may coordinate services, train workers, or fund community organizations. Local governments may support senior centers, recreation programs, or neighborhood initiatives. The Administration for Community Living offers various programs that support older adults and people with disabilities to maintain their independence while staying connected to their communities, representing the federal government's recognition of social connection as a critical component of health and well-being.

Community-based programs complement government efforts and often reach individuals who might not access formal services. Religious congregations, civic organizations, neighborhood associations, and informal mutual aid networks all contribute to the social infrastructure that protects against isolation. These grassroots efforts often succeed in engaging individuals who distrust government programs or prefer community-based support.

Case Studies or Examples of Successful Programs and Initiatives

The Silver Line (UK): This free confidential helpline provides information, friendship, and advice to older people, open 24 hours a day, every day of the year. It's a prime example of how direct communication can alleviate loneliness and isolation. The service recognizes that for many isolated individuals, having someone to talk to—even someone they have never met in person—can provide crucial emotional support and connection. Since its founding, The Silver Line has received millions of calls from lonely older adults, providing evidence of both the enormous need for such services and their value to those who use them.

Men's Sheds (Australia and worldwide): These community-based workshops provide a space where men can come together to work on projects, learn new skills, and develop social connections, addressing isolation particularly in retired men who may struggle with traditional social programming. The genius of the Men's Shed model lies in its recognition that many men find it easier to connect through shared activity than through explicit social interaction. Working side by side on woodworking, repair, or craft projects creates natural opportunities for conversation and relationship development without the pressure of explicitly social contexts.

Village to Village Network (USA): This member-driven organization helps communities establish and manage their own aging-in-place initiatives, promoting social connections and local support in a neighbor-helping-neighbor model. Villages provide members with access to services, transportation, and social activities while fostering the intergenerational connections that strengthen communities. The model empowers older adults to maintain independence while ensuring they have the social connections and practical support needed to thrive.

For more detailed insights and success stories, AARP's Connect2Affect provides a wealth of resources and examples of effective strategies and programs that have demonstrated impact in reducing isolation across diverse populations and contexts.

How These Programs Can Be Accessed and Implemented

Accessing these programs often involves reaching out to local community centers, healthcare providers, or government offices that can provide information on available services. Area Agencies on Aging serve as hubs for information about services for older adults. Community mental health centers may provide resources for those experiencing isolation-related psychological distress. Social workers, primary care providers, and faith communities can also connect individuals with appropriate programs.

Many programs have online portals or contact centers that make it easy to register or get involved. The challenge is often awareness—many people who could benefit from these programs do not know they exist. Healthcare providers, family members, and community organizations all play important roles in spreading awareness and connecting isolated individuals with resources.

Implementation can vary widely but typically involves community collaboration, funding acquisition, and ongoing evaluation to ensure effectiveness. Engaging local stakeholders, from policymakers to residents, is crucial in adapting programs to meet the specific needs of the community. What works in one context may not work in another, and successful programs typically involve significant local input in their design and operation.

For those interested in starting a program, resources like GrantSpace by Candid offer guidance on funding opportunities and project planning to ensure sustainable and impactful implementation. By leveraging these resources, communities can effectively address and prevent social isolation, fostering a more inclusive and supportive environment for all members.

How Individuals Can Help

Practical Tips for Individuals to Help Themselves or Others Around Them to Stay Connected

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

While community programs and policy changes are essential for addressing social isolation at scale, individuals also have tremendous power to prevent and reduce isolation through their own choices and actions. Every person who reaches out to a potentially isolated neighbor, maintains connection with an aging parent, or includes a marginalized colleague in social activities contributes to the social fabric that protects against isolation.

Reach Out Regularly: Make a habit of regularly checking in on friends, family, and neighbors, especially those who may live alone or who are elderly. Simple acts like phone calls, text messages, or even emails can make a significant difference in someone's day and sense of connection. Consistency matters—a weekly call becomes something to look forward to and provides structure to the relationship. For those concerned about a potentially isolated person, regular contact also allows monitoring for changes that might indicate deteriorating circumstances.

Use Technology Wisely: Embrace technology as a tool for connection by using social media, video calls, and other digital communication tools to stay connected with distant loved ones and to meet new people with similar interests. At the same time, be intentional about balancing online and offline interaction, ensuring that digital contact supplements rather than substitutes for in-person connection when possible.

Set Up Regular Meetups: Organize or participate in regular meetups, whether they're social gatherings, book clubs, walking groups, or hobby-based activities, which can help maintain a healthy social life. The regularity is key—scheduled, recurring activities create habits of connection that persist even when motivation wanes or scheduling becomes difficult.

Encouragement of Volunteerism and Participation in Local Events

Volunteer: Giving your time to local charities, hospitals, or community centers can not only help those in need but also connect you with others who share your passion for helping. Volunteering provides structured social contact, a sense of purpose and contribution, and opportunities to develop skills and relationships. For those at risk of isolation—particularly retirees who have lost workplace social networks—volunteering can provide a crucial replacement source of regular social contact and meaningful activity. Websites like VolunteerMatch can connect you with local volunteer opportunities that match your interests and availability.

Attend Local Events: Participate in community events, workshops, and lectures which can provide social interaction and new connections. Showing up is often the hardest part—once present, most people find that social interaction flows more naturally than anticipated. Check local community boards, libraries, or town websites for upcoming activities, and challenge yourself to attend something outside your usual comfort zone.

Ways to Foster Meaningful Connections in One's Daily Life

Be Open and Approachable: Sometimes, simply being open to conversation and making an effort to be more approachable can lead to new friendships and connections. Make eye contact, smile, and be willing to engage in small talk with neighbors, coworkers, and others you encounter regularly. These casual interactions can build over time into meaningful relationships.

Join Local Clubs or Groups: Engaging with a club or group that aligns with your interests can offer a consistent schedule of social interactions and the opportunity to meet like-minded individuals. Shared interests provide natural conversation topics and common ground that facilitates relationship development. Whether it's a gardening club, a hiking group, a chess club, or a religious congregation, regular participation in group activities builds the relationships that protect against isolation.

Practice Active Listening: When you do have social interactions, focus on being a good listener which can deepen your connections and make your interactions more fulfilling. Ask questions, show genuine interest in others' experiences, and resist the urge to redirect conversations to yourself. People remember those who make them feel heard and valued, and being a good listener builds the kind of deep relationships that satisfy social needs and protect against loneliness.

By implementing these strategies, individuals can play a crucial role in reducing social isolation both for themselves and others. Encouraging these behaviors can lead to more connected, supportive, and vibrant communities where isolation is less likely to take root.

Looking Ahead

Future Challenges in Combating Social Isolation

Even as understanding of social isolation grows and interventions improve, significant challenges loom on the horizon that will require continued attention and adaptation. The forces that drive isolation continue to evolve, and strategies must evolve with them.

Demographic Shifts: Aging populations across the globe present challenges in ensuring that older adults remain integrated and active in society. By 2050, the number of people over 65 will more than double globally, and in many developed countries, older adults will represent a quarter or more of the population. This demographic transformation will strain existing services and require new models for supporting social connection among the old.

Technological Advancements: While technology can help reduce isolation, there's also the risk that rapid technological changes might leave behind those who are less tech-savvy, particularly the elderly. As more social interaction, services, and daily activities move online, those who cannot or will not participate digitally may find themselves increasingly excluded. Ensuring that technology serves as a bridge rather than a barrier to connection will require intentional design and ongoing adaptation.

Urbanization and Housing: Increasing urbanization and the prevalence of single-person households can lead to greater disconnection among community members even as physical proximity increases. Urban anonymity, housing designs that prioritize privacy over community, and the decline of neighborhood-based social networks all contribute to isolation in densely populated areas.

The Role of Policy and Innovation in Creating More Inclusive Communities

Addressing the challenge of social isolation at scale requires policy attention and innovative approaches that create conditions favorable to connection while removing barriers that currently impede it.

Policy Initiatives: Governments and local authorities can develop policies that promote social inclusion, such as funding community centers, supporting programs that encourage intergenerational interactions, providing transportation for isolated individuals, and requiring social impact assessments for developments and policies that might affect community cohesion. Recognition of social connection as a social determinant of health could elevate its priority in policy making and resource allocation.

Technological Innovations: Smart technologies and social platforms can be designed to be more accessible to the elderly and disabled, ensuring that no one is left behind due to technological barriers. Age-friendly technology design, digital literacy programs, and ongoing support for technology use can help ensure that technological advances reduce rather than increase isolation.

Community Planning: Urban and community planning can play a crucial role in creating spaces that encourage social interaction, such as parks, community gardens, and pedestrian-friendly streets. Housing policies can support mixed-use development, intergenerational communities, and designs that facilitate neighbor interaction. The built environment shapes social behavior, and planning choices can either support or undermine community connection.

Frequently Asked Questions

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.