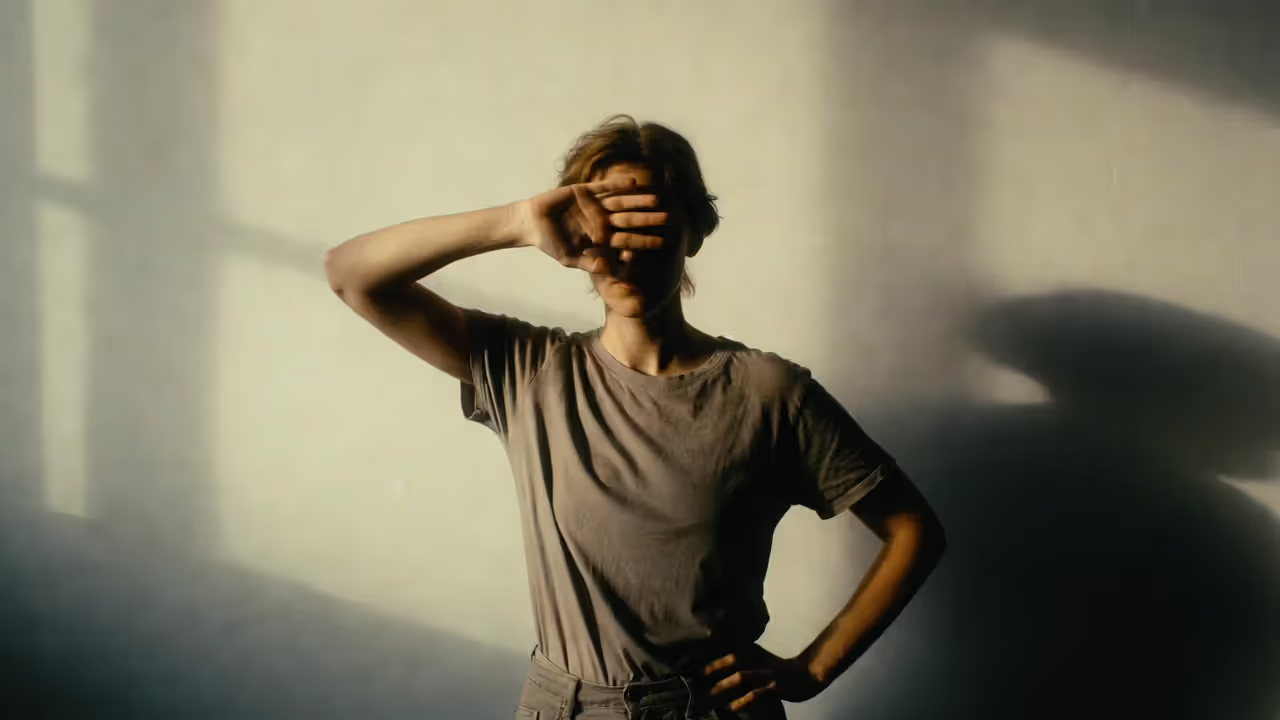

Person experiencing a panic attack

Effective Strategies for Recognizing, Avoiding, and Managing Panic Attack Triggers

Content

Content

A panic attack is a sudden and intense wave of fear that manifests with a complex array of physical symptoms including heart palpitations, chest pain, breathlessness, dizziness, and abdominal distress. These episodes arrive without warning, often reaching peak intensity within minutes, and can feel as though the world is collapsing inward even when the surrounding situation presents no actual danger. The experience is profoundly distressing—many people experiencing their first panic attack genuinely believe they are having a heart attack, dying, or losing their mind, and the terror of the experience can leave lasting psychological imprints that influence behavior long after the physical symptoms have subsided. These episodes can occur unexpectedly and are often not proportionate to the surrounding situation, creating a bewildering disconnect between internal experience and external reality that adds confusion to an already overwhelming situation.

The physiological nature of panic attacks is rooted in the activation of one of our most ancient survival mechanisms—the fight-or-flight response that evolved to protect our ancestors from predators and other life-threatening dangers. When the brain perceives danger, whether real or imagined, it initiates a cascade of neurochemical reactions that mobilize the body for immediate action. The adrenal glands release adrenaline and cortisol into the bloodstream, the heart begins beating faster to deliver more blood to the muscles, breathing quickens to increase oxygen supply, and sweating intensifies to cool the body in anticipation of physical exertion. All of these reactions are entirely adaptive when facing a genuine threat, but they become sources of terror when they occur without apparent cause—in a supermarket, during a work meeting, or in the middle of the night while lying safely in bed.

What distinguishes panic attacks from ordinary anxiety is their sudden onset, their overwhelming intensity, and the constellation of physical symptoms that accompany them. While anxiety typically builds gradually in response to identifiable stressors and manifests primarily as worry or tension, panic attacks erupt abruptly, flooding the body with stress hormones and activating the autonomic nervous system as if genuine mortal danger were present. The physical symptoms are not imagined or exaggerated—they represent real physiological changes as the body mobilizes for emergency action. Heart rate can accelerate from a resting rate of 60-80 beats per minute to 150 or higher, breathing rate increases dramatically, blood pressure rises, and muscles tense in preparation for physical exertion. These responses, so adaptive in the face of actual threats, become sources of additional terror when they occur without cause, creating a feedback loop where the symptoms themselves become frightening and thereby intensify.

The duration of panic attacks typically ranges from five to thirty minutes, with symptoms usually peaking within the first ten minutes of onset. However, the subjective experience of time during panic is dramatically distorted—minutes can feel like hours, and the attack itself can seem endless while it is happening. Some individuals experience multiple waves of panic in succession, or prolonged periods of heightened anxiety following the peak, extending the overall episode significantly beyond the typical timeframe. The aftermath of a panic attack often includes profound exhaustion, mental confusion, and lingering physical symptoms as the body recovers from the intense physiological activation. Many people describe feeling as though they have been through a physical ordeal—drained, weak, and vulnerable—a testament to the genuine physiological demands that panic places on the body.

Importance of Recognizing and Managing Triggers

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Recognizing and managing the triggers of panic attacks is crucial because it can significantly reduce the frequency and intensity of these episodes, transforming what feels like random, unpredictable terror into a more understandable and controllable condition. Understanding what precipitates a panic attack enables individuals to develop strategies to either avoid these triggers or to cope with them more effectively when avoidance is not possible or desirable. This understanding fundamentally shifts the psychological relationship with the disorder—instead of being a helpless victim of unpredictable attacks, the person becomes an informed investigator of their own condition, gathering data, testing hypotheses, and developing increasingly effective management strategies.

The concept of triggers encompasses a wide range of factors—from obvious external circumstances to subtle internal states—that can initiate the cascade of physiological and psychological events culminating in a panic attack. For some individuals, triggers are clearly identifiable: a specific phobic object, a particular location associated with previous attacks, or a recognizable pattern of stress accumulation. For others, triggers may be less apparent, involving internal states like certain thought patterns, physical sensations that get misinterpreted as dangerous, or complex interactions of multiple factors that individually might not provoke panic but together create conditions favorable to an attack. The work of identifying triggers often requires patience, systematic observation, and sometimes professional assistance to uncover patterns that are not immediately obvious.

Panic attacks rarely emerge from nowhere. More often, they represent the culmination of accumulated stress, sleep deprivation, and ignored early warning signs of anxiety. Learning to recognize these precursors gives us the opportunity to intervene before panic reaches its full intensity.

— Dr. David Barlow

Managing triggers is a vital part of therapy and self-care for those dealing with panic disorders, representing one of the most practical and empowering aspects of treatment. While medication can reduce overall anxiety levels and the severity of attacks, and while psychotherapy can address underlying psychological issues, trigger management provides day-to-day tools for navigating a world that contains potential provocations. This management involves not just avoiding problematic situations but developing the capacity to recognize early warning signs, implement coping strategies before panic escalates, and gradually build tolerance to previously triggering circumstances through systematic exposure. Resources offering insights into how triggers can be identified and managed provide valuable guidance for this process of self-discovery and skill-building.

By fostering awareness and employing targeted strategies, individuals can reclaim control over their lives and reduce the overall impact of panic attacks on their functioning and well-being. The journey from feeling helplessly at the mercy of unpredictable panic to feeling capable of understanding and managing one's responses represents one of the most significant transformations possible in panic disorder recovery. This transformation offers not just symptom reduction but genuine improvement in quality of life, self-efficacy, and the freedom to engage fully with life rather than organizing it around the avoidance of potential triggers.

Psychological Stressors as Triggers

Panic attacks can often be triggered by psychological stressors such as major life changes, including moving to a new city, changing jobs, experiencing significant relationship shifts, having children, losing loved ones, or any transition that disrupts established patterns and demands adaptation. These life changes, even when positive and desired, require psychological resources that may stretch coping capacity to its limits. The human psyche generally prefers stability and predictability; when circumstances demand significant adjustment, the resulting stress can manifest in various ways, including panic attacks for those predisposed to this response. The relationship between life stress and panic is not always immediately obvious—panic attacks often occur not at the moment of greatest pressure but days or weeks later, when the accumulated strain finally exceeds the individual's capacity to absorb it.

The mechanism connecting major life stress to panic attacks operates through several pathways that reinforce each other. On a purely physiological level, chronic stress elevates baseline arousal, keeping stress hormones elevated and the nervous system primed for threat detection. This elevated baseline means that less additional activation is required to cross the threshold into panic—the system is already running hot and needs only a small additional push to tip over into full alarm mode. Psychologically, major life changes often challenge coping resources, require more decisions than usual, and reduce access to comforting routines and relationships that normally buffer against anxiety. The loss of familiar supports during times of transition can leave individuals more vulnerable precisely when they face greater demands.

Additionally, stress at work or school can precipitate panic episodes by creating a constant state of tension and anxiety that eventually overwhelms the system's capacity to cope. Workplace stress involves multiple potential triggers: performance pressure and fear of failure, interpersonal conflicts with colleagues or supervisors, job insecurity and financial anxiety, excessive workload and inadequate recovery time, and the sense of being trapped in situations beyond one's control. Academic stress similarly combines performance pressure with social challenges and, for many students, significant life transitions occurring simultaneously. The chronic nature of these stressors matters significantly—while acute stress activates the body's emergency response and then resolves, chronic stress maintains elevated arousal indefinitely, wearing down coping resources and increasing vulnerability to panic over time.

Interpersonal conflict represents another significant psychological trigger for many individuals with panic disorder. Disagreements with partners, family members, friends, or colleagues can provoke anxiety that escalates to panic, particularly for those who are conflict-averse or who have histories of traumatic interpersonal experiences. The anticipation of difficult conversations, the experience of disagreement itself, or the aftermath of conflict can all serve as triggers. For some individuals, the fear of abandonment or rejection underlying interpersonal conflict connects to deeper psychological vulnerabilities that amplify the panic response far beyond what the immediate situation might warrant.

Perfectionism and fear of failure constitute additional psychological triggers that are particularly prevalent among high-achieving individuals. The pressure to perform flawlessly, the catastrophic interpretation of any error or shortcoming, and the harsh self-criticism that follows perceived failures create psychological conditions favorable to panic. These individuals may experience panic attacks before important presentations, during evaluations, or in any situation where their performance will be judged. The irony is that their high standards often contribute to success in many areas while simultaneously creating significant vulnerability to anxiety and panic.

Environmental Factors as Triggers

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Certain environments can trigger panic attacks by activating the threat-detection systems that evolution has built into human nervous systems, and understanding these environmental triggers is essential for developing effective management strategies. Crowded places like shopping malls, concerts, sporting events, or public transportation can be overwhelming and may lead to feelings of entrapment or helplessness that escalate to panic. The combination of limited personal space, excessive sensory stimulation, reduced control over one's movements, and perceived difficulty of escape creates conditions that the brain may interpret as threatening, activating the fight-or-flight response inappropriately. These reactions made sense in our evolutionary past, when being surrounded by many unfamiliar individuals could signal genuine danger, but they are poorly suited to modern environments where crowds rarely pose actual threats.

The phenomenon of agoraphobia—fear of situations where escape might be difficult or help unavailable—often develops in connection with panic disorder, as individuals begin avoiding environments where they have experienced or fear experiencing panic attacks. What begins as avoidance of one specific triggering environment can gradually expand to include more and more situations, progressively restricting the individual's world. A person who initially avoids only crowded shopping malls may eventually avoid all stores, then all public places, potentially becoming completely housebound in severe cases. This progressive restriction occurs because avoidance, while providing temporary relief, prevents the natural extinction of fear responses that would occur through repeated safe exposure to triggering situations.

Being in situations that have previously been associated with panic attacks can act as a powerful trigger due to the anticipatory anxiety they provoke. The brain forms strong associations between panic experiences and their contexts, creating learned triggers that can persist long after the original cause of panic has been addressed. Returning to a location where a previous attack occurred often provokes anxiety that may itself trigger another attack, reinforcing the association and strengthening the fear in a self-perpetuating cycle. This conditioning process helps explain why panic disorder tends to be self-maintaining without intervention—each attack reinforces the triggers that provoke future attacks, expanding the network of feared situations over time.

Enclosed spaces such as elevators, airplanes, tunnels, subway cars, or small rooms trigger panic in many individuals, particularly those with claustrophobic tendencies. The restriction of movement, limited air circulation (whether real or perceived), and inability to leave freely activate feelings of being trapped that can escalate rapidly to full panic. The experience of panic in enclosed spaces is often characterized by an urgent need to escape, creating significant distress when escape is not immediately possible—during flights, medical procedures like MRI scans, or even while sitting in traffic in a tunnel. Open spaces, paradoxically, can also trigger panic for some individuals; wide open areas without clear boundaries or shelter may provoke feelings of exposure, vulnerability, or disorientation in those sensitive to these environmental characteristics.

Sensory environments play a significant role in triggering panic for many individuals. Bright or flickering lights, loud or sudden noises, strong odors, temperature extremes, or chaotic visual environments can overwhelm the sensory processing system and contribute to panic. Those with sensory processing sensitivities may be particularly vulnerable to these triggers. Even subtle environmental factors like fluorescent lighting, background noise levels, or poor air quality can contribute to conditions that make panic more likely, even if they don't directly trigger attacks on their own.

Medical Triggers and Physical Factors

Some panic attacks are precipitated by medical factors that directly affect brain chemistry, nervous system function, or physical sensations in ways that provoke or mimic the panic response. Understanding these medical triggers is crucial because addressing them may significantly reduce panic attack frequency, and because misattributing medically-triggered panic to purely psychological causes delays appropriate treatment. A thorough medical evaluation should be part of the assessment for anyone experiencing panic attacks, particularly those whose attacks have atypical features or have not responded to standard psychological treatments.

The side effects of certain medications can alter brain chemistry and provoke anxiety responses that escalate to panic. Medications affecting neurotransmitter systems—particularly those influencing serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine—can sometimes produce anxiety as a side effect or during the adjustment period when starting or changing doses. Corticosteroids used for inflammation, thyroid medications, certain asthma medications containing stimulants, and some blood pressure medications have been associated with anxiety and panic in susceptible individuals. When beginning new medications or changing doses, increased anxiety or panic episodes may indicate a medication effect that should be discussed with the prescribing physician rather than assumed to be psychological in origin.

Many patients are surprised to learn that their 'unexplainable' panic attacks have quite specific physiological triggers: excess caffeine, sleep deprivation, blood sugar fluctuations. Correcting these factors often leads to dramatic improvement even before psychotherapy begins, demonstrating the intimate connection between body and mind in panic disorder.

— Dr. Michelle Craske

Stimulants like caffeine can exacerbate feelings of jitteriness and might trigger panic attacks in sensitive individuals by producing physical sensations similar to panic symptoms. Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors in the brain, preventing the calming effects of this neurotransmitter and increasing the activity of stimulating neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine. For someone already prone to panic, the racing heart, increased alertness, trembling, and jittery feelings produced by caffeine can be indistinguishable from the early stages of a panic attack—and interpreting them as such can trigger the fear response that escalates into full panic. The effects of caffeine vary enormously between individuals based on genetics, tolerance, and other factors, with some people tolerating substantial intake without problems while others experience panic symptoms from a single cup of coffee.

Moreover, lack of sleep can significantly impair the body's ability to regulate stress and anxiety, leading to increased susceptibility to panic attacks. Sleep deprivation affects the prefrontal cortex's ability to regulate the amygdala's fear responses, essentially weakening the brain's braking system for anxiety while simultaneously increasing baseline anxiety levels. Even moderate sleep restriction over several days can produce measurable increases in anxiety and emotional reactivity. For individuals with panic disorder, maintaining adequate sleep is not merely a wellness recommendation but a crucial component of panic prevention that can make the difference between manageable anxiety and frequent attacks.

Personal Triggers and Individual Sensitivities

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Personal triggers involve individual-specific factors such as phobias, traumatic memories, or unique psychological sensitivities that have developed through each person's particular history and temperament. These triggers often have their roots in personal history—experiences that taught the individual's nervous system to respond with fear to particular stimuli. Because they arise from unique individual experience, personal triggers can be some of the most challenging to identify and manage, often requiring professional assistance to fully understand and address effectively. Understanding personal triggers requires honest self-exploration and sometimes the courage to examine painful past experiences that continue to influence present reactions.

Specific phobias can trigger panic attacks when the phobic object or situation is encountered or even merely anticipated. Someone with a phobia of flying may experience a panic attack not only while on an airplane but when booking a flight, driving to the airport, or watching airplanes in movies. The anticipatory anxiety surrounding phobic situations can sometimes be more distressing than the actual encounter, creating prolonged suffering around events that might take only hours but cast shadows lasting weeks or months beforehand. Phobias vary enormously in their objects—from common fears like heights, animals, blood, or enclosed spaces to unusual fears of specific situations or objects—but share the characteristic of triggering disproportionate fear responses that can escalate to full panic.

Traumatic memories from past experiences can resurface and trigger panic attacks without warning, particularly when current circumstances contain elements reminiscent of the original trauma. This triggering can occur through obvious connections—returning to a location where trauma occurred—or through subtle associations that may not be consciously recognized. A specific smell, sound, phrase, physical sensation, or even time of year that was present during a traumatic event can trigger panic years or decades later, even when the connection to the original trauma is not consciously perceived. This explains why some panic attacks seem to come from nowhere—the trigger was present but operated below the threshold of conscious awareness.

The concept of psychological trauma encompasses not only dramatic events like accidents, assaults, or natural disasters but also developmental experiences of neglect, chronic invalidation, attachment disruption, or repeated smaller traumas that cumulatively shape the nervous system's baseline settings for threat detection. Individuals with histories of childhood adversity often have sensitized stress response systems that react more strongly to triggers and take longer to return to baseline. This developmental perspective helps explain why some people are more vulnerable to panic disorder than others with similar current circumstances, and why trigger management must sometimes address deep historical roots rather than only present circumstances.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy works not because we teach people not to be afraid. It works because we teach them that they can handle fear, that anxiety, though uncomfortable, is not dangerous, and that the situations they have been avoiding are actually manageable. This learning happens through experience, not just insight.

— Dr. David Clark

Cognitive patterns—habitual ways of thinking—serve as personal triggers for many individuals with panic disorder. Catastrophic thinking, in which mildly negative possibilities are interpreted as certain disasters, can trigger the fear response that initiates panic. Intolerance of uncertainty, where any unknown outcome is experienced as threatening, creates chronic anxiety that predisposes to panic. Perfectionism, where any flaw or mistake is experienced as catastrophic failure, generates constant performance pressure that can trigger attacks. Black-and-white thinking, where situations must be either completely safe or completely dangerous, prevents the nuanced assessment of risk that would allow appropriate responses. These cognitive patterns are often learned early in life, operate automatically without conscious deliberation, and require conscious effort and frequently therapeutic assistance to modify effectively.

Self-Monitoring: The Foundation of Trigger Recognition

One of the most effective ways to recognize personal triggers for panic attacks is through systematic self-monitoring, developing awareness of the patterns that precede and accompany panic episodes through careful observation and recording. Keeping a detailed diary of each panic attack, noting the time, place, and what was happening before and during the attack, can provide invaluable insights that might otherwise remain hidden in the chaos of the panic experience itself. This record should also include emotional states or thoughts that preceded the attack, physical sensations that may have served as early warning signs, and any substances consumed, sleep quality, exercise, menstrual cycle phase for women, or other potentially relevant factors that might contribute to vulnerability.

The panic diary becomes a data source from which patterns can emerge that would be invisible without systematic tracking over time. A person might discover through their diary that panic attacks cluster on Monday mornings, suggesting work-related triggers or weekend sleep pattern disruptions. They might notice that attacks consistently follow nights of poor sleep, indicating sleep as a critical vulnerability factor. They might identify that certain thoughts—perhaps about health, performance, or abandonment—consistently precede panic, revealing cognitive triggers that could be addressed through therapy. They might discover hormonal patterns, caffeine effects, or social situation triggers. Without the diary, these patterns would be lost in the subjective experience of panic as random and unpredictable.

Regularly updating this diary increases awareness of the conditions under which panic attacks occur and helps in identifying patterns that may not be immediately obvious from any single incident. Patterns often emerge only over time, as sufficient data accumulates to reveal correlations that isolated events cannot show. The practice of recording also has therapeutic value beyond its information-gathering function—it encourages reflection, creates psychological distance from the panic experience, reinforces the sense of agency and investigation that counteracts feelings of helpless victimhood, and provides concrete evidence of progress when attacks decrease in frequency or intensity. Many individuals find that the act of monitoring itself reduces panic frequency, perhaps because it activates the analytical prefrontal cortex in ways that reduce amygdala reactivity, or simply because the sense of doing something constructive reduces feelings of helplessness.

Self-monitoring should extend beyond panic attacks themselves to include general anxiety levels, mood states, and overall well-being measures. Tracking daily anxiety on a simple numerical scale, noting mood fluctuations throughout the day, and recording relevant life events and stressors creates a broader context within which panic attacks can be understood. This expanded monitoring often reveals that panic attacks don't emerge from nowhere but rather from escalating anxiety over hours or days, identifying opportunities for earlier intervention before panic reaches its full intensity.

Identifying Patterns and Correlations

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Identifying patterns and correlations in panic attack episodes is crucial in understanding one's personal triggers, transforming the raw data of a panic diary into actionable insights that inform prevention strategies. This analysis involves systematically reviewing recorded attacks to find commonalities across different incidents—asking what these attacks have in common that might explain their occurrence. For example, a person might notice that panic attacks frequently occur in environments where they feel trapped or unable to easily exit, during periods of high stress at work or conflict in relationships, following interpersonal confrontation, after consuming caffeine or alcohol, or when sleep-deprived. Recognizing these patterns can help individuals anticipate potential panic attacks and take preemptive steps to mitigate them.

Pattern analysis requires examining multiple dimensions of the panic experience systematically. Temporal patterns may reveal that attacks cluster at certain times of day, on particular days of the week, during certain seasons, or at particular times of the month for women who may have hormonal influences. Environmental patterns may identify specific locations, types of situations, or physical circumstances that reliably predispose to panic. Psychological patterns may illuminate specific thoughts, emotional states, or interpersonal dynamics that precede attacks. Physical patterns may reveal connections to substances consumed, sleep quality and quantity, exercise, illness, or hormonal fluctuations. Comprehensive analysis considers all these dimensions and their potential interactions.

The correlations discovered through pattern analysis should be treated as hypotheses to be tested rather than established certainties. A correlation between coffee consumption and panic attacks might indicate a direct causal relationship—caffeine triggering panic through its stimulant effects—or might reflect a third factor, such as morning anxiety that both increases coffee consumption (as an attempt to combat fatigue from anxiety-disrupted sleep) and increases panic vulnerability independently. Testing hypotheses through deliberate experiments—such as eliminating caffeine for a two-week period and observing whether panic attacks decrease—helps distinguish genuine causal triggers from coincidental associations that happen to co-occur.

The goal of pattern identification is not just intellectual understanding but prediction and prevention in daily life. Once patterns are clearly identified, the individual can anticipate high-risk periods or situations and prepare accordingly—ensuring adequate sleep before challenging events, practicing relaxation techniques when entering potentially triggering environments, avoiding caffeine when stress is high, or scheduling difficult conversations for times of lower vulnerability. This proactive stance transforms the experience of panic disorder from passive suffering to active management, building self-efficacy with each successful prediction and prevention.

Consultation with Professionals

While self-monitoring and pattern recognition can be effective starting points, consultation with a mental health professional is often necessary to fully understand and manage triggers, particularly when patterns remain unclear despite systematic tracking or when identified triggers prove resistant to self-management strategies. Psychologists, psychiatrists, and therapists are trained to help individuals delve deeper into the psychological basis of their panic attacks, bringing expertise, objectivity, and specialized tools that complement and extend self-observation.

Mental health professionals can offer assessment tools that go beyond what individuals can accomplish alone. Standardized questionnaires measure panic severity, agoraphobic avoidance, anxiety sensitivity (the tendency to fear anxiety symptoms themselves), and related constructs in ways that allow comparison to normative data and objective tracking of change over time. Clinical interviews explore history and current symptoms in depth, often uncovering connections and patterns that self-reflection might miss because they involve blind spots or material that is difficult to examine alone. Some professionals use physiological monitoring, behavioral assessment, or other specialized techniques that provide additional information about triggers and responses.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy represents the gold standard psychological treatment for panic disorder, and its effectiveness stems partly from its systematic approach to trigger identification and management. CBT therapists help patients identify the thoughts that trigger panic, examine the evidence for and against these catastrophic thoughts, and develop more balanced interpretations that reduce anxiety. They guide patients through exposure exercises that systematically confront triggers in a graduated manner, building tolerance and reducing fear through repeated successful experience. They teach coping strategies—breathing techniques, cognitive restructuring skills, behavioral approaches—that can be deployed when triggers are encountered, providing practical tools for managing symptoms both during and between sessions.

Moreover, professionals can provide a more structured approach to exposure therapy, where patients gradually face their triggers in a controlled environment, reducing their impact over time. Self-directed exposure often fails because individuals either avoid too completely, preventing any corrective learning, or expose themselves too intensely, traumatizing rather than desensitizing themselves. Professional guidance helps calibrate exposure difficulty appropriately, ensures adequate support during and after exposure exercises, and processes the experience afterward in ways that maximize therapeutic benefit. The combination of professional expertise with the individual's self-knowledge typically produces better outcomes than either approach alone.

Strategies to Avoid Panic Attack Triggers

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

One straightforward strategy for managing panic attacks is to avoid known triggers whenever possible, reducing exposure to situations, substances, or circumstances that have been identified as reliable precipitants. If a person knows that crowded places or specific social settings trigger panic, planning to minimize exposure to these environments can be beneficial in the short term and while building coping capacity. This might involve choosing less crowded times for necessary shopping, opting for online meetings when large gatherings are particularly stressful, selecting airplane seats that feel less confining, or declining invitations to events likely to provoke panic during vulnerable periods.

Strategic avoidance can be a reasonable component of an overall management approach, particularly in the early stages of treatment or during especially vulnerable periods when coping resources are depleted. Not every triggering situation needs to be confronted immediately; choosing battles wisely and avoiding unnecessary exposure while building coping skills can support recovery rather than impede it. The key is distinguishing between strategic avoidance that serves recovery goals and excessive avoidance that reinforces fear and progressively restricts life. Strategic avoidance is time-limited, purposeful, and part of a larger plan that includes eventual engagement with feared situations; excessive avoidance is open-ended, fear-driven, and progressively expanding.

While avoidance can be helpful temporarily, it is critically important to balance this with the goal of not overly restricting one's lifestyle or reinforcing the fear that drives panic disorder. Excessive avoidance is a hallmark of agoraphobia and can progressively narrow a person's world until very little feels safe. Each time avoidance provides relief from anticipated anxiety, it reinforces the belief that the avoided situation was genuinely dangerous and that avoidance was necessary for safety, strengthening the fear rather than reducing it. Over time, avoidance can become more limiting than the panic attacks themselves, trapping individuals in increasingly constricted lives organized entirely around the prevention of panic rather than the pursuit of meaningful goals and experiences.

Gradual Exposure: Building Tolerance to Triggers

Gradual exposure therapy is a therapeutic approach designed to desensitize individuals to their triggers, representing one of the most effective and well-validated interventions for panic disorder and related anxiety conditions. This method involves slowly and systematically exposing a person to the source of their anxiety in a controlled and incremental manner, allowing the nervous system to learn through direct experience that the feared situation is actually safe. Over time, this can reduce the intensity of the panic response by acclimating the individual to the trigger in a safe setting where they repeatedly discover that feared outcomes do not occur.

The mechanism of exposure therapy involves several psychological processes working together. Habituation occurs as repeated exposure to a stimulus naturally reduces the intensity of response—the same mechanism that allows us to stop noticing background noises or adjust to initially uncomfortable water temperature. Extinction of conditioned fear occurs as the learned association between the trigger and panic weakens when trigger exposure repeatedly occurs without the expected catastrophic consequences. Cognitive change occurs as the individual accumulates evidence disconfirming their fearful beliefs, learning experientially rather than just intellectually that they can tolerate anxiety, that panic does not lead to the feared disasters, and that avoided situations are actually manageable.

This therapy is often guided by professionals who can ensure that the exposure is conducted in a supportive environment, minimizing the risk of overwhelming panic during the process while maximizing therapeutic benefit from each exposure. The therapist helps design an exposure hierarchy—a graduated sequence of exposure exercises ranging from minimally anxiety-provoking to maximally challenging—and guides the patient through this hierarchy at a pace that stretches capacity without overwhelming it. Professional guidance also ensures that exposure is conducted correctly: with adequate duration for anxiety to peak and begin declining naturally, without subtle avoidance behaviors that undermine learning, and with helpful cognitive processing afterward that consolidates gains.

Interoceptive exposure specifically targets the physical sensations associated with panic, helping individuals become less reactive to the body sensations that often trigger or escalate panic attacks. This approach involves deliberately inducing sensations similar to panic symptoms—spinning in a chair to create dizziness, breathing through a narrow straw to create breathlessness, running in place to increase heart rate and produce sweating—and allowing the resulting anxiety to naturally diminish without escape or avoidance. Through repeated interoceptive exposure, individuals learn that these body sensations, while uncomfortable, are not dangerous and do not inevitably lead to catastrophe, reducing the catastrophic misinterpretation that often fuels the panic cycle.

Lifestyle Adjustments for Trigger Prevention

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Making specific lifestyle adjustments can significantly help in avoiding triggers for panic attacks, creating physiological and psychological conditions less favorable to panic. These modifications address modifiable factors that influence baseline anxiety levels, stress tolerance, and vulnerability to panic, providing a foundation upon which other management strategies can build more effectively. While lifestyle adjustments alone may not be sufficient for severe panic disorder, they create conditions that support the effectiveness of other treatments and reduce the overall burden of the condition.

Reducing caffeine intake represents one of the most straightforward and effective lifestyle adjustments for many individuals with panic disorder. Since caffeine is a stimulant, it can exacerbate anxiety and trigger panic attacks in sensitive individuals by producing physical arousal that mimics panic symptoms and can be misinterpreted as threatening. Limiting or eliminating caffeine—including hidden sources like chocolate, some medications, certain teas, and even decaffeinated coffee (which still contains some caffeine)—can help in managing these symptoms, though the transition should be gradual to avoid withdrawal symptoms that might themselves trigger anxiety. Individuals vary considerably in their caffeine sensitivity, so experimentation may be needed to identify the intake level that minimizes symptoms without unnecessarily restricting a substance many people enjoy.

Ensuring adequate sleep is crucial for panic management because sleep deprivation impairs the brain's ability to regulate emotion and increases anxiety reactivity through multiple mechanisms. Establishing a regular sleep schedule with consistent bedtimes and wake times, creating a restful sleeping environment that is dark, quiet, and cool, limiting screen exposure and stimulating activities before bed, and addressing any sleep disorders that might be present are critical steps in managing anxiety and reducing panic vulnerability. Many individuals with panic disorder have comorbid sleep difficulties—insomnia, nighttime panic attacks, or anxiety-disrupted sleep—and addressing these can produce substantial improvements in daytime panic symptoms.

Managing overall stress through regular physical activity, relaxation practices, and adequate leisure time can significantly reduce panic attack frequency by lowering baseline anxiety levels and building resilience to stressors. Exercise has demonstrated anti-anxiety effects comparable to medication for many individuals, likely through multiple mechanisms including neurotransmitter effects, stress hormone regulation, improved sleep, and increased self-efficacy. Regular exercise—ideally most days of the week, at moderate intensity, for at least thirty minutes—should be considered a first-line intervention for panic disorder that complements rather than competes with other treatments.

Coping Mechanisms When Exposure is Inevitable

For people with panic disorder, mastering coping techniques can be a powerful tool in managing symptoms during a panic attack when avoiding triggers is not possible. These techniques provide concrete tools for getting through panic episodes with less distress and faster recovery, reducing the overall burden of the condition even when attacks cannot be entirely prevented. Having reliable coping strategies also reduces anticipatory anxiety by providing confidence that attacks, if they occur, can be managed effectively—the fear of panic often exceeds the actual difficulty of the panic experience itself.

Relaxation techniques such as deep breathing and mindfulness meditation help calm the mind and reduce the physical symptoms of panic by activating the parasympathetic nervous system. Deep breathing involves slow, deliberate breaths that help decrease the heart rate and promote a sense of calm, counteracting the rapid, shallow breathing that typically occurs during panic and contributes to symptoms through hyperventilation. The technique is simple but requires practice to be accessible during actual panic: breathe in slowly through the nose for a count of four, hold briefly, then exhale slowly through the mouth for a count of six or eight. This extended exhale activates the vagus nerve and the parasympathetic system, signaling safety to the body and reducing the physiological arousal that drives panic symptoms.

Mindfulness meditation focuses on being present in the moment and observing one's thoughts and sensations without judgment, which can help lessen the intensity of panic attacks by reducing the struggle against symptoms. Rather than fighting panic—which tends to intensify it through additional arousal and catastrophic thinking—mindfulness encourages accepting the present experience as it is, observing it with curiosity rather than fear, and allowing it to pass naturally without resistance. This non-resistant stance often accelerates the resolution of panic symptoms, as the absence of struggle removes one of the factors that typically prolongs and intensifies episodes.

Grounding techniques help individuals maintain connection to the present moment and external reality during panic, counteracting the dissociative tendencies and sense of unreality that often accompany severe anxiety. The 5-4-3-2-1 technique involves identifying five things you can see, four you can touch, three you can hear, two you can smell, and one you can taste, systematically engaging the senses to anchor attention in the present moment rather than in catastrophic thoughts about what might happen. Physical grounding through contact with solid surfaces, cold water on the face or wrists, or strong sensory stimulation can interrupt panic spirals by providing compelling sensory input that competes for attention with internal fear signals.

Cognitive-Behavioral Strategies for Panic Management

Cognitive-behavioral strategies are essential for people with panic disorder, enabling them to challenge and reframe the irrational fears that often trigger panic attacks and maintain the disorder over time. These strategies address the thinking patterns that interpret normal body sensations as dangerous, predict catastrophic outcomes from anxiety symptoms, and reinforce avoidance through fearful anticipation. Cognitive restructuring is a method used to identify and dispute irrational or maladaptive thoughts, which can alleviate the psychological intensity of a panic attack both during episodes and preventively by changing the underlying beliefs that make panic likely.

The cognitive model of panic disorder holds that attacks often begin with the catastrophic misinterpretation of body sensations as dangerous—noticing an increase in heart rate and thinking "I'm having a heart attack," feeling dizzy and thinking "I'm going to faint or lose consciousness," experiencing breathlessness and thinking "I'm suffocating or can't get enough air," or noticing feelings of unreality and thinking "I'm going crazy or losing my mind." These catastrophic interpretations trigger intense fear, which produces more body sensations through physiological arousal, which trigger more catastrophic interpretations, creating a rapidly escalating feedback loop that culminates in full panic. Breaking this cycle by providing more accurate interpretations is central to cognitive treatment.

Techniques for cognitive restructuring include examining the evidence for and against anxious automatic thoughts that arise during panic or in anticipation of it. When the thought "I'm having a heart attack" arises during panic, cognitive techniques encourage systematic evidence examination: "I've experienced this exact sensation many times before and it wasn't a heart attack. My doctor has examined my heart and found it completely healthy. The sensation is entirely consistent with anxiety arousal, not cardiac symptoms. My previous panic attacks felt exactly like this and all resolved without any medical emergency." This evidence examination doesn't eliminate the uncomfortable sensations but can reduce the fear attached to them, preventing the escalation that transforms discomfort into full panic.

Behavioral experiments test catastrophic predictions through deliberate experience, providing powerful experiential evidence against anxious beliefs that may be more convincing than verbal cognitive work alone. If someone believes "If I let myself feel panic in public, I'll completely lose control, make a scene, and everyone will stare at me in horror," a behavioral experiment might involve deliberately allowing panic symptoms to occur in a public setting and observing what actually happens. Typically, the predicted catastrophe doesn't occur—panic symptoms are far less visible to others than feared, other people are absorbed in their own concerns and barely notice, and the individual copes better than expected even when anxiety is high. These experiments provide experiential learning that often has more impact than purely cognitive approaches.

Support Systems and Their Role

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Utilizing support systems effectively is critical for individuals experiencing panic attacks, providing emotional comfort, practical assistance, and the reassurance that comes from not facing a difficult condition alone. Friends, family, support groups, and professional networks can offer presence during or after panic episodes, help with tasks that anxiety makes difficult, and provide the validation and encouragement that sustain recovery efforts over the long course of treatment. For many people, knowing that support is available reduces the intensity of anticipatory anxiety and increases willingness to attempt challenging exposures that are necessary for recovery.

Communicating about panic disorder with trusted others is an important step in building a support network that can actually help. Many individuals feel embarrassed about their panic symptoms and hide them from others, depriving themselves of potential support and adding the burden of concealment to the burden of the disorder itself. While discretion may be appropriate in some contexts, having at least a few people who understand the condition and can provide support is valuable for managing difficult periods. Education may be needed, as friends and family members who haven't experienced panic themselves may not understand the condition or may offer well-meaning but unhelpful advice. Sharing accurate information about panic disorder—what it is, what it feels like, what helps and what doesn't—enables supporters to provide more effective assistance.

Sharing experiences with others who understand the symptoms of panic can also lessen the stigma and isolation that often accompanies panic disorder. Finding others who have experienced similar struggles normalizes the condition, provides modeling of successful coping and recovery, and offers practical suggestions from those who have faced the same challenges and found solutions. The reduction in shame that comes from discovering one is not alone in this struggle, that many capable people have experienced similar difficulties, can itself have significant therapeutic value, lifting a psychological burden that often compounds the direct difficulty of the condition.

Support groups specifically for anxiety and panic can offer a network of encouragement and coping strategies shared by peers facing similar challenges. These groups may meet in person, providing the benefits of physical presence, human connection, and community, or may operate online, offering accessibility to those who live in areas without local groups or who find in-person meetings too anxiety-provoking to attend initially. Both formats have demonstrated value, and many people find that participation in support groups complements individual therapy effectively.

When to Seek Professional Help

Recognizing when to seek professional help is crucial for effectively managing panic disorder, as self-help strategies, while valuable, have limitations that professional treatment can address more effectively. Key indicators that professional intervention may be necessary include the frequency and intensity of panic attacks—if attacks are happening more often than occasionally, are becoming more intense over time, or have begun occurring without identifiable triggers, this pattern suggests that the condition may be progressing beyond what self-management can address effectively.

Another critical indicator is the impact of panic episodes on quality of life and daily functioning. If panic attacks have begun to restrict your activities—causing you to avoid work, school, social events, or other important parts of life—or if they have led to persistent worry about having another attack that occupies significant mental energy and interferes with concentration and enjoyment, it is advisable to consult a professional. These impacts suggest that panic disorder is significantly impairing functioning in ways that warrant formal treatment. The development of agoraphobic avoidance patterns—increasingly widespread avoidance of situations where panic might occur—indicates that professional intervention is needed before these patterns become deeply entrenched and more difficult to reverse.

Several therapeutic options with strong evidence bases are available for managing panic disorder professionally. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective treatments, validated through decades of controlled research and recommended as first-line treatment by major clinical guidelines. CBT for panic disorder focuses on changing the thought patterns that trigger panic attacks, teaching patients to recognize and challenge catastrophic misinterpretations of body sensations, and guiding systematic exposure to feared situations and sensations. Medication—particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—can help manage the symptoms of panic disorder, reducing attack frequency and severity with regular use. Combined treatment using both medication and psychotherapy is often the most effective approach for moderate to severe cases, addressing both immediate symptoms and underlying psychological factors.

Conclusion

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Understanding the triggers of panic attacks and learning effective management strategies are crucial steps towards gaining control over panic disorder, transforming what can feel like random, overwhelming terror into a condition that can be understood, predicted, and managed effectively. Throughout this article, we have explored the common triggers of panic attacks, including psychological stressors that accumulate and overwhelm coping capacity, environmental factors that activate evolved threat-detection systems inappropriately, medical conditions and substances that affect nervous system function, and personal sensitivities rooted in individual history, temperament, and learning. We have examined how these triggers interact, often combining in ways that produce panic attacks when no single factor would be sufficient alone.

We have discussed how to recognize personal triggers through systematic self-monitoring that reveals patterns invisible to casual observation, through analysis of diary data that identifies correlations between circumstances and attacks, and through professional consultation that brings expertise and objectivity to the process of understanding one's own experience. This recognition transforms panic from a random, unpredictable affliction into a comprehensible phenomenon that follows discoverable rules and responds to targeted intervention.

We have outlined practical strategies for avoiding triggers when appropriate and for building tolerance through gradual exposure when avoidance is not serving recovery goals. Lifestyle modifications that reduce baseline anxiety and vulnerability to panic—adequate sleep, limited caffeine, regular exercise, stress management—provide a foundation upon which other strategies build more effectively. Coping mechanisms including relaxation techniques, cognitive strategies, and support systems offer tools for managing panic when it occurs, reducing both the intensity of episodes and the anticipatory fear of future attacks that so often maintains the disorder.

The importance of these strategies cannot be overstated, as they empower individuals to significantly reduce the frequency and severity of panic attacks, thereby improving overall quality of life and functioning. It is essential for anyone dealing with panic attacks to adopt proactive measures, whether that means making lifestyle adjustments, practicing relaxation techniques, engaging in cognitive-behavioral therapy, or seeking medication when appropriate. Passive suffering is not the only option; active engagement with one's condition, informed by understanding and equipped with effective strategies, offers a genuine path toward recovery.

By understanding your triggers, employing coping strategies systematically, and knowing when to seek professional help, you can navigate the challenges of panic disorder more effectively than you might have believed possible. Everyone has the potential to overcome the difficulties posed by this condition, and taking proactive steps towards managing panic attacks represents a decisive move towards a more balanced and fulfilling life. The path from panic's grip to manageable anxiety to genuine freedom is one that many have traveled; with understanding, effort, and appropriate support, it can be traveled successfully.

This article provides general information about panic attack triggers and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you are experiencing panic attacks, please consult with a qualified healthcare provider or mental health professional for personalized guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.