Person experiencing a panic attack

Decoding the Storm Within: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Panic Attacks

A panic attack is a sudden onset of intense fear or discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes and includes a variety of physical and psychological symptoms. These episodes can occur unexpectedly and are often not triggered by any apparent cause, striking without warning in situations that pose no actual danger. The experience is profoundly distressing—individuals frequently describe panic attacks as among the most terrifying experiences of their lives, sometimes comparing them to the sensation of dying or losing complete control over their minds and bodies.

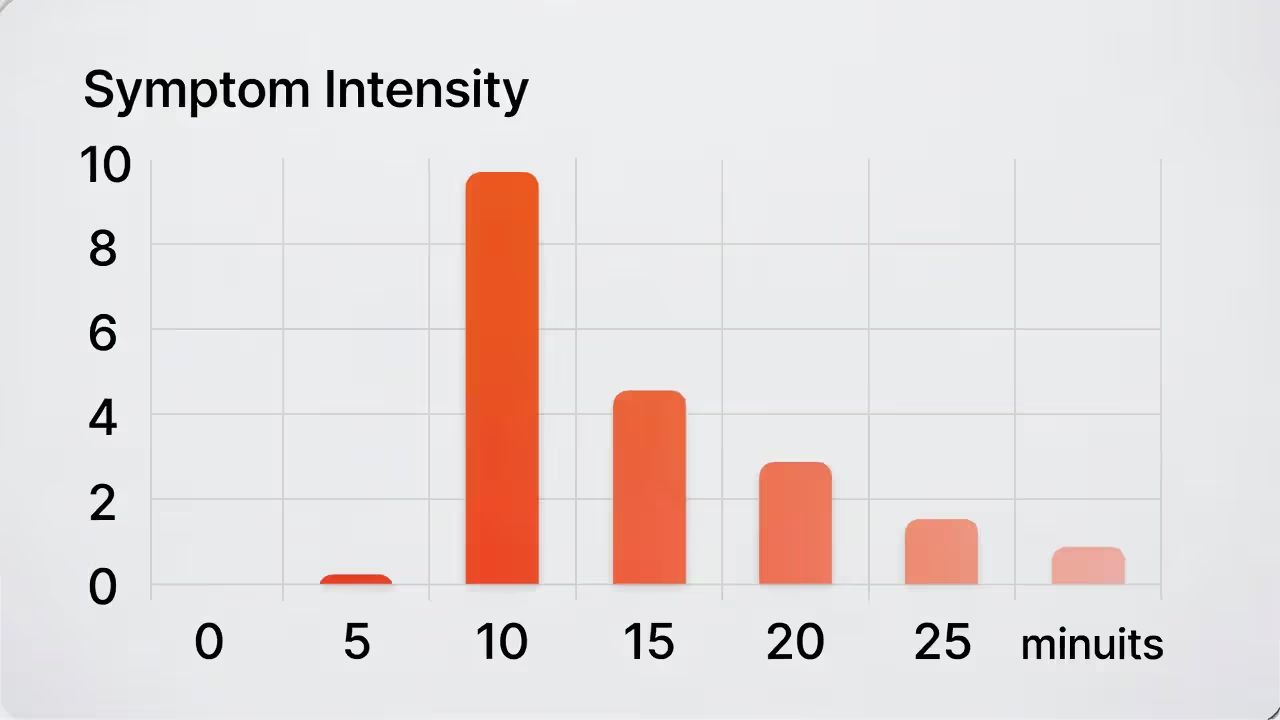

The American Psychological Association describes panic attacks as involving at least four of the following symptoms: palpitations, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, feelings of choking, chest pain, nausea, dizziness, a feeling of being detached from oneself, fear of losing control or dying, numbness or tingling sensations, and chills or hot flashes. What makes panic attacks particularly challenging is that these symptoms appear suddenly and escalate rapidly, typically reaching their maximum intensity within ten minutes or less. The body essentially activates its emergency response system in the absence of any genuine threat, creating a cascade of physical sensations that feel genuinely dangerous even though they pose no actual medical risk.

The distinction between panic attacks and general anxiety is important for understanding the condition. While anxiety tends to build gradually in response to perceived stressors and can persist for extended periods, panic attacks are acute events—sudden eruptions of fear that appear seemingly from nowhere and subside relatively quickly, usually within twenty to thirty minutes. This sudden onset is part of what makes panic attacks so disorienting; individuals often cannot identify what triggered the episode, leading to confusion and heightened fear about when the next attack might occur.

Brief Overview of the Prevalence and Impact on Daily Life

Panic attacks are relatively common, affecting an estimated 2-3% of adults in the United States each year, with lifetime prevalence rates suggesting that up to 11% of the population will experience at least one panic attack during their lives. They can occur in the context of panic disorder, which is diagnosed if someone experiences recurrent and unexpected panic attacks followed by at least one month of persistent concern about having another attack or behavioral changes related to the attacks. However, panic attacks can also occur in individuals with other anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even in people without any diagnosed mental health condition.

The impact on daily life can be profound and far-reaching, extending well beyond the actual moments of panic. Fear of future attacks may lead individuals to avoid places, situations, or activities where previous attacks have occurred, a pattern that can progressively narrow their world. Someone who experienced a panic attack while driving might avoid highways, then local roads, then driving altogether. A person who panicked in a crowded store might begin avoiding all shopping centers, then any crowded space. This avoidance behavior, while understandable as an attempt to prevent future attacks, often backfires—it reinforces the brain's association between certain situations and danger, potentially making the fear response even stronger over time.

The fear of panic attacks can become more debilitating than the attacks themselves. Patients often restructure their entire lives around avoiding triggers, which paradoxically maintains and strengthens the disorder rather than providing genuine relief.

— Dr. David Barlow

This avoidance can severely restrict a person's ability to work, attend school, or maintain personal relationships, leading to significant life disruptions. Career advancement may stall when someone cannot attend meetings, travel for work, or handle high-pressure situations. Relationships suffer when panic prevents participation in social events, family gatherings, or even simple outings with friends. The cumulative effect can include social isolation, financial difficulties from reduced work capacity, and secondary depression arising from the limitations panic imposes on life (source: National Institute of Mental Health).

Symptoms of Panic Attacks

Physical Symptoms

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Panic attacks manifest with a variety of intense physical symptoms that typically escalate quickly and can feel overwhelming. These symptoms are not imaginary or exaggerated—they represent real physiological changes occurring in the body as the autonomic nervous system activates its emergency response. Understanding that these symptoms, while terrifying, are not medically dangerous is crucial for individuals learning to manage panic attacks.

Heart palpitations or accelerated heart rate: This can feel like your heart is pounding out of your chest or beating very fast without any physical exertion. The heart rate during a panic attack can increase to 150-180 beats per minute or higher, similar to what might occur during intense physical exercise. This cardiovascular response is part of the body's preparation for physical action—the heart pumps harder and faster to deliver oxygen-rich blood to muscles that might need to fight or flee. Many individuals experiencing their first panic attack believe they are having a heart attack, and this symptom alone drives countless emergency room visits each year.

Sweating: Excessive sweating is common even if you are not physically active or in a warm environment. This perspiration serves an evolutionary purpose—it cools the body in preparation for physical exertion and makes the skin slippery, potentially harder for a predator to grip. During a panic attack, individuals may notice cold, clammy hands, sweating across the forehead and upper lip, or general perspiration throughout the body despite feeling cold.

Trembling or shaking: Uncontrollable shaking or trembling can occur, often as a response to intense fear. This tremor results from the surge of adrenaline coursing through the body and the tension in muscles preparing for action. The shaking can be visible to others, which sometimes adds embarrassment to the already distressing experience, or it may be an internal sensation that the individual feels acutely but others cannot see.

Shortness of breath or a feeling of being smothered: This may feel like you can't get enough air, which can heighten feelings of panic. Paradoxically, during panic attacks, individuals often hyperventilate—they breathe too quickly and shallowly, taking in more air than the body needs. This over-breathing actually decreases carbon dioxide levels in the blood, which can cause lightheadedness, tingling in extremities, and a sensation of not getting enough air even though oxygen levels remain normal.

Nausea or abdominal distress: This can range from mild discomfort to severe pain in the stomach area. The digestive system essentially shuts down during the stress response as blood is diverted to muscles and vital organs. This can cause nausea, stomach cramps, or the urgent need to use the bathroom. Some individuals find this symptom particularly disabling, as it can occur in situations where access to facilities is limited.

These physical responses are part of the body's acute stress response system, often termed the "fight or flight" response, which is intended to prepare the body to face a perceived immediate threat. The system evolved over millions of years to protect our ancestors from predators and other dangers, and it remains incredibly effective at preparing the body for physical action. The problem in panic attacks is that this powerful system activates when no actual threat exists, creating a mismatch between the body's state of high alert and the benign reality of the situation.

Psychological Symptoms

The psychological symptoms of a panic attack are just as impactful as the physical ones and often intertwine with them in ways that intensify the overall experience. These cognitive and emotional symptoms can be deeply disturbing and may persist in memory long after the physical symptoms have subsided.

Overwhelming fear of disaster or losing control: This can happen even in the absence of real danger and is often disproportionate to the situation. Individuals may feel certain that something catastrophic is about to happen—that they will collapse, go crazy, make a fool of themselves publicly, or somehow be unable to cope. This fear feels absolutely real and compelling in the moment, even if the person intellectually recognizes that nothing dangerous is actually occurring.

Detachment from reality or depersonalization: Individuals may feel detached from themselves or their surroundings, as if they are observing themselves from outside their body. This dissociative experience, called depersonalization when it involves feeling detached from oneself or derealization when the world seems unreal, can be one of the most frightening aspects of a panic attack. People describe feeling like they're in a dream, watching themselves from a distance, or like the world around them has become artificial or unfamiliar. While disconcerting, this symptom represents a protective mechanism—the brain's attempt to create psychological distance from an overwhelming experience.

Fear of dying: This extreme fear can dominate the episode, making the experience particularly terrifying. With the heart racing, breath coming in gasps, and physical sensations overwhelming the body, it is entirely understandable that people believe they are dying. First-time panic sufferers frequently call emergency services or rush to hospital emergency rooms convinced they are experiencing a medical emergency. The fear of death during a panic attack is not irrational given the intensity of the physical symptoms—it is a logical interpretation of sensations that truly feel life-threatening.

These symptoms reflect the intense anxiety and fear that characterize panic attacks and can contribute to the debilitating nature of the condition. The psychological symptoms often feed back into the physical ones, creating a vicious cycle—noticing a racing heart triggers fear, fear accelerates the heart further, the faster heartbeat increases fear, and so on. Understanding this cycle is fundamental to learning how to interrupt it.

Managing Panic Symptoms

Duration and Onset of Symptoms

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Panic attacks typically come on suddenly and without warning, arriving like a storm that appears from a clear sky. The onset can be so abrupt that it catches individuals completely off-guard, which can further exacerbate their anxiety. One moment a person might be engaged in routine activity—working at their desk, shopping for groceries, or even sleeping—and the next moment they are engulfed in overwhelming fear with their body responding as if facing mortal danger.

Symptoms usually peak within minutes—typically 10 minutes or less—and then gradually subside as the stress hormones are metabolized and the body's relaxation response begins to activate. The duration of the entire episode can vary but often ends as quickly as it began, usually resolving within 20 to 30 minutes, leaving the individual exhausted and confused about what triggered the attack. Some people experience longer episodes or multiple waves of symptoms, but even in these cases, the peak intensity is typically brief.

The aftermath of a panic attack can be significant. Many individuals feel physically drained, as if they have completed strenuous exercise—because, in a sense, they have. The body has just undergone an intense physiological activation that burns energy and depletes stress hormones. Emotional exhaustion is common, as is a lingering sense of vulnerability or apprehension. In some cases, the fear of another attack can linger, affecting the person's mental health long after the physical symptoms have subsided (source: Mayo Clinic).

Understanding the comprehensive range of symptoms associated with panic attacks is crucial for recognizing and addressing them effectively, especially since they can mimic other health issues like heart disease or breathing disorders. Many people suffer through multiple panic attacks before receiving an accurate diagnosis, often visiting emergency rooms or cardiologists first because the symptoms so closely resemble cardiac events. Education about panic attacks—both for potential sufferers and healthcare providers in non-psychiatric settings—is essential for ensuring timely and appropriate treatment.

Causes and Risk Factors

Genetic Predispositions

Research suggests that panic attacks and panic disorder can run in families, indicating a genetic component that influences vulnerability to these conditions. Studies have identified specific genes that may influence the risk of developing anxiety disorders, including those that affect neurotransmitters such as serotonin and noradrenaline. These neurotransmitters are involved in regulating mood and response to stress, and variations in the genes that control their production, release, or reception can alter how the brain processes fear and threat.

Twin studies have been particularly illuminating in establishing the hereditary nature of panic disorder. Research consistently shows that identical twins, who share 100% of their genetic material, have higher concordance rates for panic disorder than fraternal twins, who share only about 50% of their genes. This pattern strongly suggests genetic influence, though the fact that concordance is not 100% even among identical twins indicates that environmental factors also play important roles.

A family history of anxiety disorders or panic attacks significantly increases the likelihood of an individual experiencing similar conditions. First-degree relatives of people with panic disorder have a risk approximately four to seven times higher than the general population. However, having a genetic predisposition does not guarantee that someone will develop panic attacks—it simply means they may be more vulnerable if exposed to triggering environmental conditions (source: Anxiety and Depression Association of America).

The genetics of panic are complex and involve multiple genes, each contributing small effects rather than a single "panic gene" determining outcomes. Current research focuses on identifying specific genetic variants and understanding how they interact with each other and with environmental factors to produce vulnerability to panic attacks. This research holds promise for eventually developing more targeted treatments based on individual genetic profiles.

Environmental Triggers

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

External factors play a crucial role in the onset of panic attacks, and for many individuals, environmental triggers serve as the spark that ignites the underlying vulnerability. These triggers can vary widely among individuals but commonly include:

Significant life changes: Such as starting a new job, marriage, having a baby, moving to a new city, or any major transition that disrupts familiar routines and support systems. Even positive changes can trigger panic in vulnerable individuals because change itself requires adaptation and can activate the brain's threat-detection systems.

Stressful events: Such as financial troubles, the death of a loved one, divorce, job loss, or serious illness in oneself or a family member. These stressors tax coping resources and can create conditions where panic attacks become more likely. Cumulative stress—the gradual accumulation of multiple smaller stressors—can be as significant as single major events.

Physical health issues: Chronic conditions or serious illnesses can heighten anxiety, contributing to panic attacks. Conditions that affect breathing, heart function, or hormonal balance may be particularly likely to trigger panic because their symptoms can overlap with or mimic panic symptoms. Additionally, the stress of managing a chronic illness adds psychological burden that can lower the threshold for panic.

Substance use: Caffeine, alcohol, and drugs can provoke or exacerbate panic attacks in susceptible individuals. Caffeine is a stimulant that can increase heart rate and create physiological arousal similar to the early stages of a panic attack. Alcohol, while initially calming, can trigger rebound anxiety as it leaves the system. Recreational drugs, particularly stimulants and cannabis, are known triggers for many people.

Understanding the environmental contexts that can trigger panic attacks is essential for managing and potentially preventing them. Many individuals benefit from keeping journals to track potential triggers, identifying patterns that can inform avoidance strategies or targeted preparation for high-risk situations.

Psychological Factors

Certain psychological characteristics and mental health issues can predispose individuals to panic attacks, creating fertile ground in which panic can take root and flourish:

Stress: Chronic or acute stress is a common trigger for panic attacks, as it can overwhelm an individual's ability to cope effectively. When stress hormones remain elevated over extended periods, the body's baseline state shifts toward greater arousal, making the threshold for triggering a full panic response lower. What might have been manageable anxiety before chronic stress can escalate into full-blown panic in an overstressed system.

Personality traits: Traits such as perfectionism, a tendency to be overly self-critical, high anxiety sensitivity (the fear of anxiety symptoms themselves), and neuroticism can increase stress levels, making individuals more susceptible to panic attacks. People who are highly attuned to bodily sensations may be more likely to notice and become alarmed by the subtle physiological changes that precede panic, inadvertently triggering the very response they fear.

Anxiety sensitivity—the fear of fear itself—is one of the strongest predictors of panic disorder development. People who interpret arousal symptoms as dangerous create a self-fulfilling prophecy where normal bodily sensations become triggers for panic.

— Dr. Steven Taylor

Other mental health disorders: Conditions like depression, other anxiety disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often co-occur with panic attacks. The relationship can be bidirectional—depression can create conditions favorable for panic to develop, while the limitations imposed by panic can trigger or worsen depression. PTSD involves a sensitized threat-detection system that may make panic attacks more likely.

These psychological factors can create a predisposition to panic attacks by influencing how individuals perceive and react to stressors. Importantly, many of these factors are modifiable through therapy, offering hope that even those with high inherent vulnerability can learn to reduce their risk.

Role of the Brain and Nervous System

The brain and nervous system are central to the development and experience of panic attacks, serving as both the origin and the battlefield of these episodes. Understanding the neuroscience of panic has advanced significantly in recent decades, revealing a complex interplay of brain structures and chemical messengers.

Abnormalities in brain function, particularly in areas that regulate fear and anxiety, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, play a critical role in panic attacks. The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped structure deep in the brain that serves as the fear center—it rapidly processes potential threats and can trigger the body's alarm response before conscious thought even occurs. In individuals prone to panic attacks, the amygdala may be hyperactive, responding to stimuli that would not trigger fear in others or producing responses disproportionate to actual threat levels.

The hippocampus, involved in memory formation and context processing, helps determine whether a situation is genuinely dangerous based on past experience. Problems with hippocampal function may contribute to panic by impairing the brain's ability to accurately assess whether current circumstances warrant a fear response. This could explain why panic attacks often occur in situations that the individual intellectually recognizes as safe—the emotion-processing amygdala overrides the context-processing hippocampus.

Neuroimaging studies have shown that people with panic disorder may have an overly reactive sympathetic nervous system, which controls the "fight or flight" response. This heightened reactivity can lead to more frequent and intense responses to perceived threats, culminating in panic attacks. The interplay between neurotransmitter imbalances and nervous system activity is a key area of ongoing research, aiming to better understand and treat panic-related disorders (source: National Institute of Mental Health).

The role of carbon dioxide sensitivity has also emerged as important in understanding panic. Research shows that many individuals with panic disorder are unusually sensitive to elevated carbon dioxide levels, which the brain interprets as a suffocation threat. This sensitivity may explain why hyperventilation—which lowers carbon dioxide—is both a symptom of and an ineffective coping attempt during panic attacks.

Overall, the causes of panic attacks are multifaceted, involving a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors, all influenced by individual brain and nervous system functioning. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for effective prevention and treatment strategies, and it helps individuals recognize that panic attacks are not personal failures but rather the result of identifiable biological and psychological processes.

Diagnosis and Assessment

How are Panic Attacks Diagnosed?

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Diagnosing panic attacks primarily involves clinical evaluation by a mental health professional, though the path to accurate diagnosis often begins elsewhere—in emergency rooms, cardiology offices, or primary care settings where individuals first seek help for frightening physical symptoms. This process is critical for distinguishing panic attacks from other types of anxiety disorders and medical conditions that might mimic panic attack symptoms, such as heart disease, thyroid problems, respiratory disorders, or vestibular dysfunction.

Mental health professionals typically use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria, which require the sudden onset of intense fear or discomfort along with at least four additional physical or cognitive symptoms. The diagnosis of panic disorder is considered if the attacks are recurrent and unexpected, and if they have significant impact on the person's behavior or cause persistent worry about further attacks. The distinction between isolated panic attacks and panic disorder matters for treatment planning—while a single panic attack may resolve without intervention, panic disorder typically requires structured treatment to prevent worsening (source: American Psychiatric Association).

The diagnostic process involves careful history-taking to understand the nature, frequency, and context of panic episodes. Clinicians ask detailed questions about what the individual experiences during attacks, what situations seem to trigger them, how the person responds, and how the attacks have affected their life. This information helps distinguish panic from other conditions and identifies factors that may be maintaining the disorder.

Tools and Tests Used

To accurately diagnose panic attacks and panic disorder, several tools and methods are utilized, combining standardized assessments with individualized clinical judgment:

Psychological questionnaires: These are designed to assess symptoms of panic attacks and other anxiety disorders. Commonly used questionnaires include the Panic and Agoraphobia Scale (PAS), the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS), the Anxiety Sensitivity Index, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. These instruments provide standardized measurements that can track symptom severity over time and assess treatment response.

Clinical interviews: Structured or semi-structured interviews are crucial for understanding the frequency, severity, and context of the panic attacks. These interviews help to gather detailed personal and family medical histories, which are essential for a comprehensive assessment. The interview allows clinicians to explore nuances that questionnaires might miss and to build rapport that facilitates honest disclosure of symptoms.

Behavioral observations: These might be conducted during or after a panic attack occurs, if possible, to note the nature of the symptoms directly. While it is not always feasible to observe a panic attack as it happens, clinicians may note anxiety symptoms during assessment sessions or gather reports from family members who have witnessed attacks.

These diagnostic tools help in forming a complete picture of the individual's mental health and are crucial for accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment planning. The combination of multiple assessment methods provides greater diagnostic confidence than any single approach.

The Importance of Medical Evaluation to Rule Out Other Conditions

Medical evaluations are crucial to exclude physical health issues that might be causing symptoms similar to panic attacks. This step is not merely procedural—it is essential for patient safety and treatment accuracy. The symptoms of panic attacks overlap significantly with several medical conditions, and mistaking a medical problem for panic (or vice versa) can have serious consequences.

Physical exams: To check for signs of physical health problems that could explain or contribute to symptoms. This includes assessment of vital signs, cardiovascular examination, neurological screening, and general physical assessment.

Laboratory tests: Including blood tests to check thyroid function (both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can cause anxiety-like symptoms), blood glucose levels (hypoglycemia can mimic panic), and other possible irregularities. Blood tests can also screen for anemia, electrolyte imbalances, and other conditions that might contribute to symptoms.

Electrocardiograms (ECG): To rule out heart-related conditions, particularly cardiac arrhythmias that can cause palpitations similar to those experienced during panic attacks. In some cases, longer-term cardiac monitoring may be recommended.

This step is important because many symptoms of panic attacks, like chest pain and heart palpitations, can also be symptoms of physical health issues. Ruling out these conditions ensures that the treatment for panic attacks is appropriate and targeted to the actual cause. Additionally, receiving medical clearance can be therapeutic for individuals with panic—knowing that their heart and lungs are healthy can reduce the fear that panic symptoms represent dangerous medical events.

Overall, the process of diagnosing panic attacks is comprehensive, involving a combination of psychological evaluation and medical tests to ensure an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan. This thorough approach helps to differentiate panic attacks from other medical and psychological conditions, paving the way for effective management.

Treatment Options

Medication

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Medication is a common and effective treatment for panic attacks and panic disorder, offering relief for many individuals who struggle with frequent or severe episodes. Medications can reduce the frequency and intensity of panic attacks, decrease anticipatory anxiety, and help individuals engage more fully in psychotherapy. The types of medications typically prescribed include:

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine. These are often the first choice because they are generally safe and tend to have fewer side effects than older medications. SSRIs work by increasing serotonin availability in the brain, which helps regulate mood and anxiety. They typically take several weeks to reach full effectiveness and are intended for long-term use rather than immediate relief.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs): Such as venlafaxine and duloxetine. These are another class of antidepressants used to treat panic disorder, working on both serotonin and norepinephrine systems. They may be particularly helpful for individuals who also experience depression or chronic pain alongside panic.

Benzodiazepines: Such as alprazolam and clonazepam. These are fast-acting anti-anxiety medications but are generally prescribed only for short-term relief due to risks of dependency. Benzodiazepines can provide rapid relief during acute panic and may be used as a bridge while waiting for SSRIs to take effect. However, their potential for dependence and withdrawal symptoms limits their long-term utility.

While effective, these medications can have side effects, including nausea, headache, sleep disturbances, sexual dysfunction, and, with benzodiazepines, dependency issues. It's important for patients to discuss these potential side effects with their healthcare providers, weigh the benefits against the risks, and participate actively in medication management decisions (source: National Institute of Mental Health).

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is highly effective for many people with panic disorder and is often considered the first-line treatment, either alone or in combination with medication. Unlike medications, which manage symptoms, psychotherapy addresses the underlying patterns of thought and behavior that maintain panic disorder, offering the possibility of lasting change that persists even after treatment ends.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): This therapy focuses on identifying and changing thinking and behavior patterns that trigger or exacerbate panic attacks and developing ways to reduce anxiety. CBT for panic typically includes psychoeducation about the nature of panic, cognitive restructuring to challenge catastrophic interpretations of symptoms, and behavioral experiments to test feared predictions. CBT has the strongest evidence base for panic disorder treatment and produces lasting improvements for most individuals who complete treatment.

Exposure Therapy: This involves gradual exposure to the fears and situations that provoke panic attacks to build up tolerance and reduce panic-related anxiety. For panic disorder, this often includes interoceptive exposure—deliberately inducing feared physical sensations (such as rapid breathing, dizziness, or increased heart rate) to learn that these sensations are not dangerous. Situational exposure addresses avoidance of places or activities associated with panic.

Exposure-based treatments work by allowing patients to learn through experience that their feared outcomes don't occur, and that they can tolerate the sensations of anxiety without catastrophe. This learning happens in the body, not just the mind.

— Dr. Michelle Craske

These therapies can help individuals understand their panic attacks better, develop strategies to cope with them, and reduce their frequency and intensity. The skills learned in therapy become tools that individuals carry with them throughout life, providing protection against relapse.

Lifestyle Changes and Coping Strategies

Adopting healthier lifestyle choices and learning effective coping strategies can significantly help manage and reduce panic attacks. While these approaches may not be sufficient as standalone treatments for severe panic disorder, they form an important foundation that enhances the effectiveness of other treatments:

Regular exercise: Helps in managing stress and anxiety by burning off stress hormones, releasing endorphins, and providing opportunities for mastery and accomplishment. Regular aerobic exercise has been shown to reduce anxiety sensitivity and may decrease panic attack frequency.

Adequate sleep: Poor sleep can exacerbate anxiety and panic disorders. Sleep deprivation increases emotional reactivity and impairs the brain's ability to regulate fear responses. Establishing good sleep hygiene—consistent sleep schedules, appropriate sleep environment, and relaxation before bed—supports anxiety management.

Mindful eating: Reducing caffeine and sugar intake can decrease episodes of panic. Caffeine is a stimulant that can trigger panic symptoms in sensitive individuals, while blood sugar fluctuations from high-sugar diets can create physiological states that mimic or trigger panic.

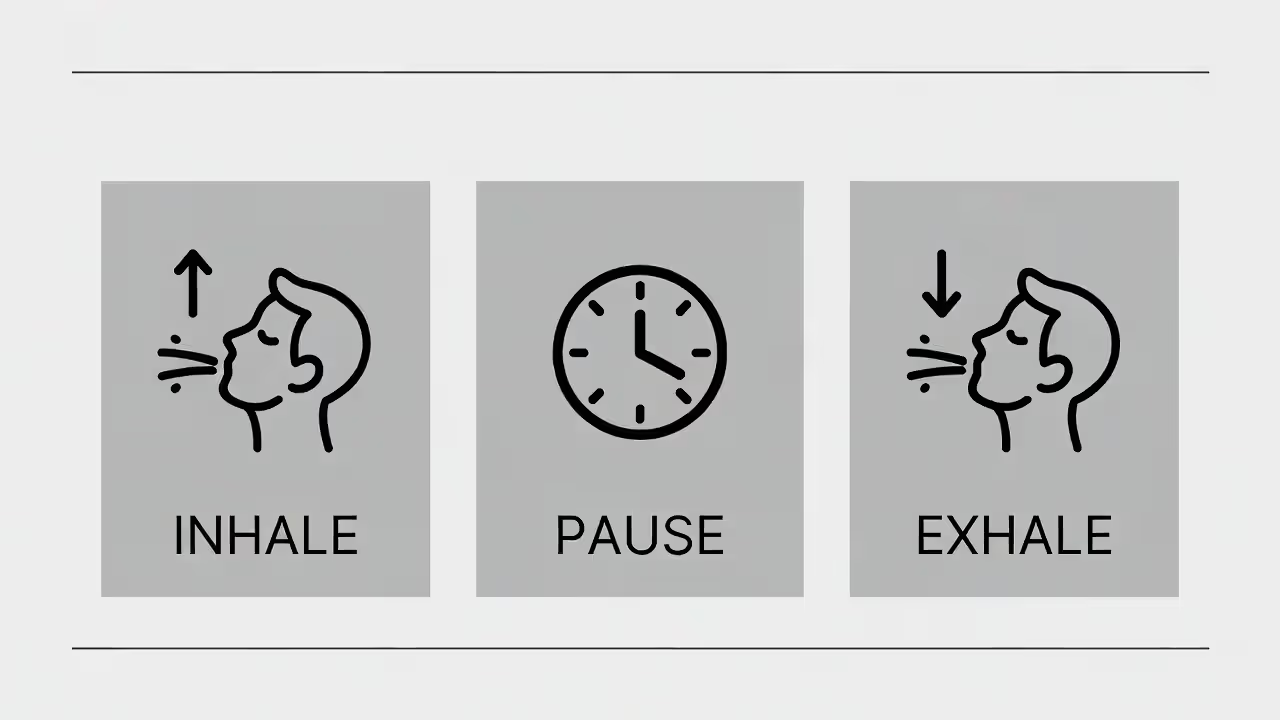

Stress management techniques: Such as deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness meditation. These techniques activate the parasympathetic nervous system, counteracting the fight-or-flight response and creating a state of calm that is incompatible with panic.

These changes can enhance overall well-being and reduce the likelihood of panic attacks, while also improving quality of life in ways that extend beyond panic management.

Alternative Treatments

Alternative therapies can complement traditional treatments for panic disorder, offering additional tools for individuals seeking comprehensive approaches to their care:

Mindfulness Meditation: Helps in cultivating a state of awareness and presence, reducing overall anxiety. Mindfulness teaches individuals to observe their thoughts and sensations without judgment, reducing the tendency to catastrophize or struggle against uncomfortable experiences.

Yoga: Combines physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditation to improve mental well-being. The breathing practices in yoga may be particularly beneficial for panic, as they teach respiratory control and reduce the tendency toward hyperventilation.

Acupuncture: Some find acupuncture helpful for managing anxiety and stress. While research evidence is mixed, acupuncture may work for some individuals through placebo effects, relaxation responses, or mechanisms not yet fully understood.

These alternative approaches offer additional tools for individuals to manage their symptoms, often with minimal to no side effects. They work best as complements to evidence-based treatments rather than replacements.

The combination of these treatments, tailored to the individual's specific needs, symptoms, and preferences, provides the best chance for effectively managing and reducing the impact of panic attacks. Treatment plans should be developed collaboratively between patients and providers, reviewed regularly, and adjusted based on response.

Managing Panic Attacks

Immediate Strategies to Handle a Panic Attack

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

When a panic attack strikes, having immediate strategies can help mitigate the intensity and duration of the episode. These techniques work by interrupting the escalating cycle of panic and activating the body's natural calming systems:

Deep Breathing: Focusing on slow, deep breaths can counteract the rapid breathing that accompanies a panic attack, reducing symptoms of hyperventilation and helping to calm the body. A simple technique involves breathing in slowly through the nose for a count of four, holding briefly, then exhaling slowly through the mouth for a count of six or eight. The extended exhale activates the parasympathetic nervous system, signaling safety to the body.

Grounding Techniques: Techniques such as the 5-4-3-2-1 method, which involves identifying five things you can see, four you can touch, three you can hear, two you can smell, and one you can taste, can help distract from the panic and reconnect with the environment. Grounding brings attention to the present moment and external reality, interrupting the internal focus on frightening sensations.

Mindfulness: Staying present in the moment can prevent the escalation of distressing thoughts that fuel a panic attack. Rather than fighting or fleeing from panic sensations, mindfulness involves observing them with curiosity and acceptance, which paradoxically often reduces their intensity.

Recognize and Accept: Understanding that you are experiencing a panic attack and reminding yourself that it will pass can reduce fear and help you regain control. Saying to yourself, "This is a panic attack. I have survived these before. It will end," can provide reassurance and prevent catastrophic thinking from amplifying the episode.

Long-term Strategies to Reduce Frequency and Severity

To manage and reduce the frequency of panic attacks over the long term, several approaches can be effective when applied consistently:

Regular Psychotherapy: Engaging in ongoing psychotherapy, especially cognitive-behavioral therapy, helps modify the thought patterns that trigger panic attacks. Therapy provides a structured environment for learning and practicing skills that become protective against future attacks.

Medication Management: Regularly taking prescribed medications can help to stabilize mood and prevent panic attacks. Working closely with prescribers to optimize medication regimens, manage side effects, and adjust doses as needed is important for long-term success.

Lifestyle Modifications: Consistent exercise, a healthy diet, adequate sleep, and avoiding stimulants like caffeine can significantly impact overall anxiety levels. These modifications reduce baseline arousal levels, making panic attacks less likely to be triggered.

Stress Management: Learning and practicing stress management techniques such as yoga, meditation, and deep breathing exercises can help maintain a calm state of mind. Regular practice builds skills that are available during times of stress and reduces the overall burden on the nervous system.

Role of Support Groups and Therapy

Support groups and therapy play a vital role in the management of panic attacks by providing resources that extend beyond individual coping:

Emotional Support: Sharing experiences and struggles with others who understand can reduce feelings of isolation and stigma often associated with panic disorder. Knowing that others have faced similar challenges and recovered can instill hope.

Coping Strategies: Support groups can be a resource for learning new coping techniques and hearing what has worked for others in similar situations. Peer learning often provides practical tips that formal treatment might not cover.

Motivation and Encouragement: Regular meetings can provide motivation to continue with treatment and encouragement during setbacks. The accountability of group participation can help individuals persist through difficult periods.

Therapeutic Benefits: Participating in group therapy provides professional guidance and structured support, which can enhance the benefits of individual treatments. Group settings also offer opportunities for practicing skills like exposure in a supportive environment.

Managing panic attacks involves a combination of immediate and long-term strategies tailored to an individual's specific needs. Integrating these strategies into daily life, along with active participation in support groups or therapy, can significantly improve the quality of life for those suffering from panic attacks.

Challenges and Misconceptions

Common Misconceptions About Panic Attacks

Misunderstandings about panic attacks can lead to significant challenges for those experiencing them, affecting both their self-perception and the responses they receive from others. Common misconceptions include:

"It's just stress": Many people dismiss panic attacks as merely a stress response, not recognizing them as intense episodes of fear that require treatment. While stress can contribute to panic, panic attacks involve distinct physiological activation that goes beyond ordinary stress reactions. Minimizing panic as "just stress" can delay appropriate treatment and leave sufferers feeling unheard.

"Panic attacks can cause fainting": Contrary to popular belief, fainting is rare during a panic attack because the sympathetic nervous system actually increases blood pressure. Fainting typically results from a sudden drop in blood pressure, which is the opposite of what happens during panic. The feeling that one might faint is common during panic, but actual fainting is not.

"People can just 'snap out of it'": There is a misconception that individuals can control or stop their panic attacks at will, which undermines the severity of the disorder and the person's experience. Panic attacks involve involuntary nervous system activation that cannot be stopped through willpower alone. Telling someone to "calm down" or "snap out of it" is not only unhelpful but can increase their distress and shame.

Stigma Associated with Mental Health Disorders

Stigma remains a significant barrier to seeking treatment for panic attacks and other mental health issues, preventing many individuals from accessing help that could transform their lives. Factors contributing to stigma include:

Misinformation and stereotypes: Many societal views about mental health are based on inaccurate information, leading to prejudices against those affected. Media portrayals often sensationalize mental illness, contributing to misconceptions about what panic disorder looks like and who experiences it.

Social judgment: People may fear being judged as weak, unstable, or "crazy" due to their mental health condition, which can discourage them from discussing their experiences or seeking help. This fear can lead to suffering in silence and delay treatment.

Workplace discrimination: Concerns about potential negative repercussions at work, such as discrimination, loss of job opportunities, or being passed over for promotions, can also deter people from seeking treatment or disclosing their condition. These concerns are not always unfounded, though legal protections exist in many jurisdictions.

Challenges in Finding Appropriate Care and Support

Navigating the healthcare and social support systems can be daunting, especially when trying to find effective treatment for panic attacks:

Access to healthcare: Not everyone has equal access to mental health services. Barriers can include geographic location, cost, insurance coverage, and availability of specialists like psychiatrists or therapists trained in treating anxiety disorders. Rural areas and underserved communities often lack adequate mental health resources.

Lack of understanding: Even within the healthcare system, individuals can face providers who are not well-versed in the nuances of panic disorders, leading to misdiagnosis or inadequate treatment. Some providers may dismiss symptoms or offer only medication without psychotherapy referrals.

Social support: Those suffering from panic attacks often struggle to find understanding and support from family, friends, and colleagues, which is crucial for long-term management and recovery. Loved ones may not understand the condition or may inadvertently enable avoidance behaviors.

Addressing these challenges requires ongoing efforts to educate the public, improve healthcare provider training, increase accessibility to mental health services, and reduce stigma through open conversation and accurate representation. Those with panic attacks deserve understanding, support, and effective treatment.

Summary of Key Points

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Panic attacks are sudden, intense surges of fear and discomfort accompanied by a variety of physical and psychological symptoms that can be profoundly disabling despite their relatively brief duration. They can be triggered by genetic factors that create vulnerability, environmental influences that precipitate episodes, and psychological stressors that maintain the cycle of fear, with the brain and nervous system playing crucial roles in their manifestation. The amygdala, hippocampus, and autonomic nervous system work together in ways that can produce false alarms—emergency responses to situations that pose no actual danger.

Diagnosis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, psychological questionnaires, and medical tests to rule out other conditions that might mimic panic symptoms. This thorough approach ensures that treatment is appropriately targeted and that medical conditions are not missed. Effective treatment options include medications that stabilize neurochemistry, psychotherapy that addresses thought patterns and behaviors, lifestyle adjustments that reduce vulnerability, and alternative therapies that provide additional coping tools—all tailored to the individual's needs and preferences.

Management strategies focus on both immediate techniques to alleviate panic attacks when they occur and long-term approaches to reduce their frequency and severity. These strategies work best when integrated into daily life and supported by professional guidance and peer support. Despite significant advances in understanding and treating panic, significant challenges remain due to misconceptions that minimize the condition, stigma that prevents help-seeking, and barriers to accessing care that leave many without adequate treatment.

Encouragement for Seeking Help and Support

If you or someone you know is struggling with panic attacks, it's crucial to seek help. Panic attacks are highly treatable, and effective interventions exist that can dramatically improve quality of life. Engaging with healthcare providers who specialize in anxiety disorders can offer effective treatments and support, and should not be delayed due to shame or fear of judgment.

Additionally, joining support groups or connecting with others facing similar challenges can provide comfort, practical coping strategies, and hope for recovery. Online communities now make support accessible even to those in areas without local resources. It's important to remember that seeking help is a sign of strength, not weakness, and is the first step towards recovery.

Future Directions in Research and Therapy

Research into panic attacks continues to evolve, with promising directions that include:

Personalized Medicine: Tailoring treatment approaches based on individual genetic profiles, symptom patterns, and treatment response could enhance the effectiveness of therapy and reduce side effects. Biomarkers may eventually help match patients with the most likely effective treatments.

Neurobiological Studies: Further understanding the brain structures and functions related to panic attacks can lead to more targeted interventions. Advances in neuroimaging allow researchers to observe the brain during panic and understand what distinguishes those who develop panic disorder from those who do not.

Technological Innovations: The use of digital tools, smartphone apps, and teletherapy to reach a broader population and provide real-time assistance during panic attacks is expanding. Virtual reality exposure therapy shows promise for treating panic-related avoidance.

Integrative Treatments: Combining traditional and alternative therapies to address both the physical and psychological aspects of panic attacks is gaining traction, offering more comprehensive approaches to care.

As our understanding deepens and stigma decreases, the future holds potential for more effective and accessible treatments, improving the lives of those affected by panic attacks. Recovery is possible, and help is available—the first step is reaching out.

This article provides general information about panic attacks and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you are experiencing panic attacks, please consult with a qualified healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.