The Psychology of Procrastination: Why Your Brain Thrives on Delays

The Psychology of Procrastination: Why Your Brain Thrives on Delays

Procrastination is one of the most perplexing and universal human behaviors, a paradox that has puzzled philosophers, psychologists, and ordinary people struggling to meet their deadlines for centuries. Despite knowing with absolute certainty that delaying important tasks often leads to stress, missed opportunities, poor performance, damaged relationships, and a cascade of negative consequences, we continue to procrastinate with remarkable consistency. Whether it's postponing work assignments until the last possible moment, delaying household chores until they become overwhelming, putting off important health appointments, or avoiding difficult decisions that could improve our lives, procrastination is something nearly everyone struggles with at some point—and for many people, it becomes a chronic pattern that significantly diminishes their quality of life and prevents them from reaching their full potential.

The fascinating and somewhat counterintuitive truth is that procrastination is not simply a result of laziness, poor time management, or a deficient character. At its core, procrastination is deeply rooted in psychology and neuroscience, emerging from the complex architecture of the human brain and the emotional challenges of navigating a world filled with tasks we find aversive, overwhelming, or threatening to our sense of self. Our brains are wired in intricate ways that often prioritize short-term emotional comfort over long-term goals, leading us to delay tasks despite our conscious knowledge of the consequences and our sincere intentions to act differently.

In this comprehensive exploration, we will examine the psychology of procrastination from multiple angles, uncovering the neurological mechanisms that make delay so tempting, the emotional and psychological drivers that fuel avoidance behavior, and the profound impacts that chronic procrastination can have on mental health, relationships, and life satisfaction. Most importantly, we will offer evidence-based insights and practical strategies on how to break free from the procrastination cycle. Whether you're a chronic procrastinator seeking liberation from a pattern that has held you back for years, or simply curious about why humans put things off despite their best intentions, understanding the brain's inner workings can help you take control of your productivity, your emotional well-being, and ultimately your life.

What Is Procrastination?

Procrastination is the act of intentionally delaying or postponing a task that needs to be accomplished, even when you know that completing it is important and that delay will likely lead to negative consequences. While procrastination is often viewed simplistically as a matter of willpower, motivation, or time management skills, the reality is far more complex and interesting. Procrastination involves cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components interacting in intricate ways, making it a multifaceted phenomenon that requires much more than discipline or better scheduling to overcome.

Understanding procrastination requires recognizing that it is fundamentally different from simple delay or thoughtful prioritization. When you consciously decide to postpone a task because other tasks are genuinely more urgent or important, that's prioritization—a rational allocation of limited time and resources. When you delay because you're waiting for necessary information or resources, that's practical timing. Procrastination, in contrast, involves delay despite knowing that delay is irrational and counterproductive, delay that is not justified by the circumstances but driven by internal psychological factors that override our better judgment.

Procrastination is not a time management problem, it's an emotion management problem. We delay tasks not because we lack organizational skills, but because we want to avoid the negative emotions associated with the task—boredom, anxiety, frustration, self-doubt, or fear of failure.

— Dr. Tim Pychyl

There are two primary types of procrastination that researchers have identified:

Active Procrastination: Some individuals deliberately delay tasks but still consistently meet deadlines by working intensively under pressure. These people appear to thrive in high-stress, time-limited environments and may genuinely believe—sometimes correctly—that they produce their best work when time constraints create focus and adrenaline. Active procrastinators maintain a sense of control over their delay, use the time pressure strategically, and generally do not experience the same negative emotional consequences as passive procrastinators. However, this pattern still carries risks, including increased stress, reduced quality of work compared to what might be achieved with more time, and vulnerability to unexpected complications that leave no buffer.

Passive Procrastination: This more problematic form occurs when individuals postpone tasks without strategic intent and experience significant stress, guilt, shame, or regret as a result. Passive procrastinators often struggle to get started on tasks, feel paralyzed by the prospect of beginning, fail to complete work in a timely manner, and suffer substantial negative consequences both practically and emotionally. They typically feel out of control of their procrastination, wish they could stop, and experience the delay as something happening to them rather than something they are choosing.

While active procrastination may appear more functional on the surface, both forms of procrastination share common underlying psychological mechanisms and both can benefit from greater understanding of why we delay and how to develop healthier patterns of engagement with our responsibilities and goals.

The Neuroscience of Procrastination: What Happens in Your Brain?

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

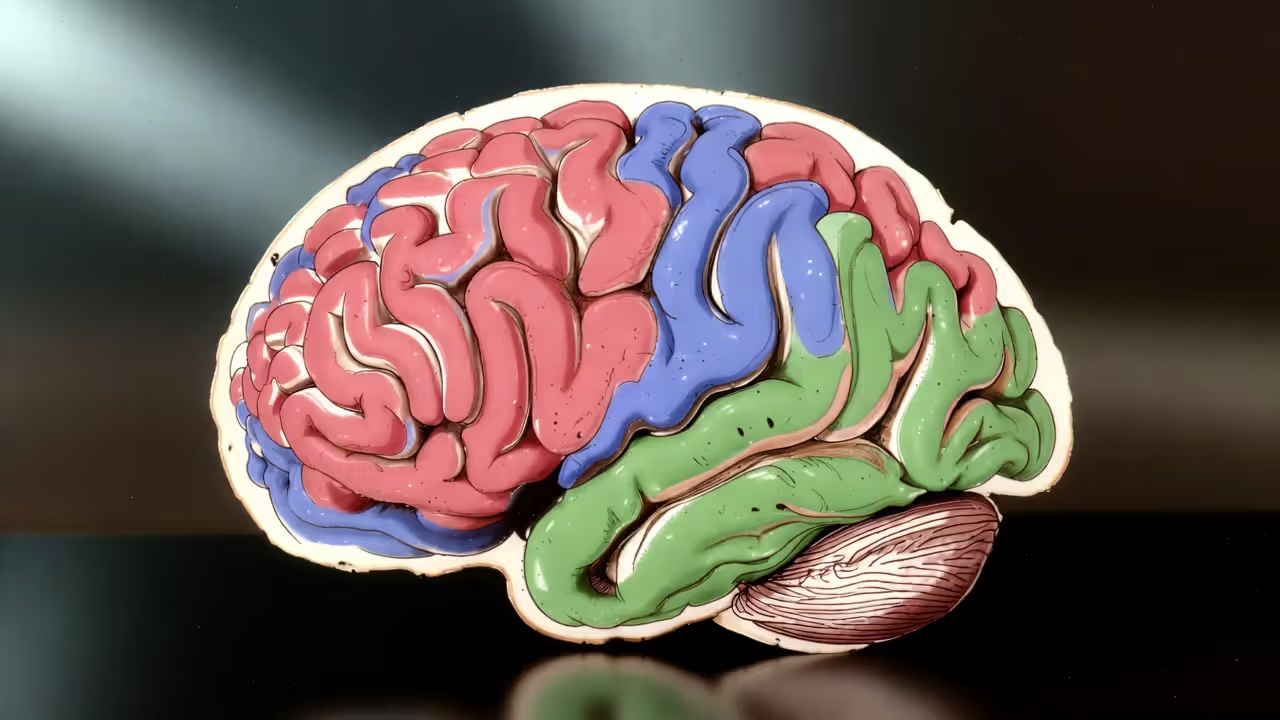

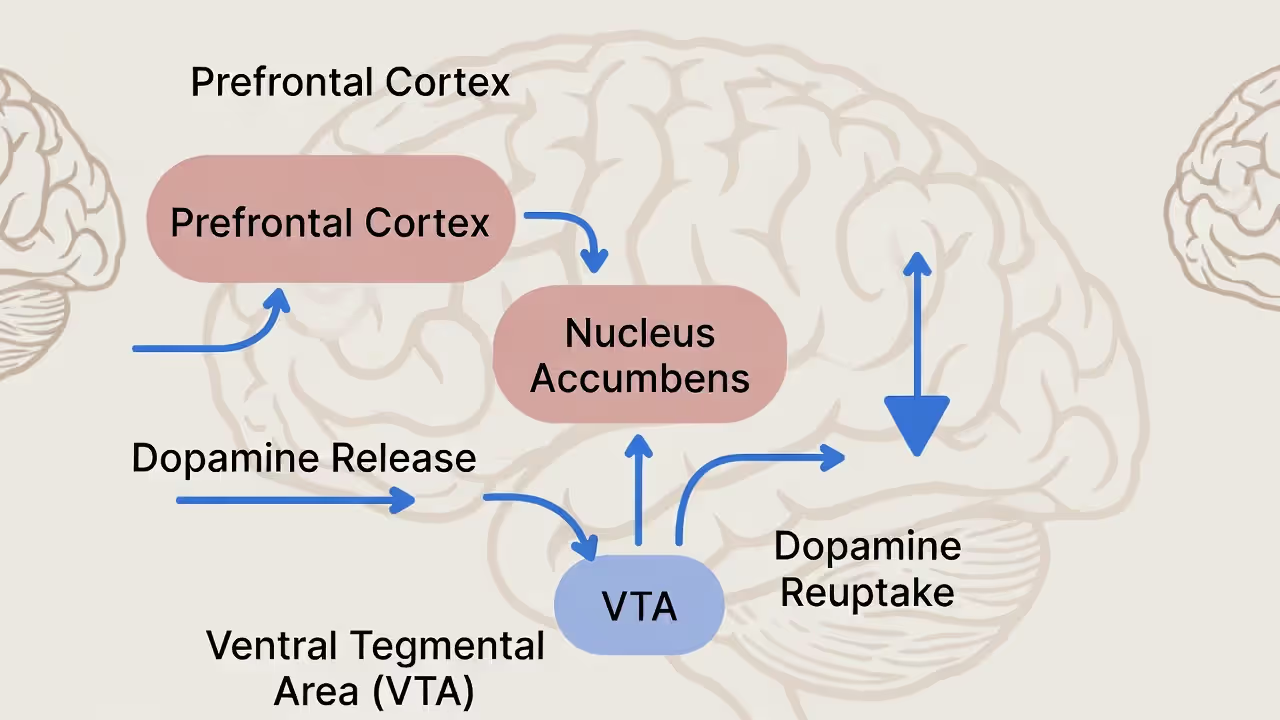

At the neurological core of procrastination lies the brain's natural and evolutionarily ancient tendency to prioritize immediate rewards, comfort, and safety over long-term goals that require present sacrifice. This phenomenon, which behavioral economists call temporal discounting or delay discounting, can be understood through the interaction between several key brain structures, particularly the limbic system, the prefrontal cortex, and the dopamine-based reward circuitry that motivates behavior based on anticipated pleasure.

The Limbic System: The Pleasure-Seeking Part of Your Brain

The limbic system is a collection of evolutionarily ancient structures located deep within the brain, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, that are responsible for processing emotions, forming memories, and driving motivated behavior toward rewards. Often referred to as the brain's "pleasure center" or "emotional brain," the limbic system fundamentally seeks immediate gratification, short-term rewards, and avoidance of discomfort. This system evolved over millions of years to help our ancestors survive by prioritizing things that required immediate action—finding food when hungry, fleeing danger, seeking warmth when cold, pursuing mating opportunities when available. In the ancestral environment, delay could be fatal, so the limbic system evolved to be impulsive and present-focused.

When faced with a task that seems unpleasant, boring, difficult, or emotionally threatening—like writing a challenging report, having a difficult conversation, filing taxes, or beginning a daunting project—the limbic system registers this as something to be avoided, similar to how it would register a physical threat or source of pain. It encourages you to escape the discomfort by redirecting attention toward something more pleasurable in the short term: scrolling through social media, watching entertaining videos, snacking, checking messages, or engaging in any of the countless distractions readily available in our modern environment. The limbic system doesn't consider future consequences; it simply drives you toward what feels good now and away from what feels bad now.

The limbic system's influence on procrastination manifests through several mechanisms:

- Emotional avoidance: The limbic system generates negative emotions (anxiety, dread, boredom) in response to aversive tasks, then motivates escape from these feelings through avoidance behavior

- Reward seeking: It constantly scans the environment for sources of immediate pleasure and novelty, making distractions highly salient and attractive compared to difficult tasks

- Present bias: The limbic system heavily discounts future consequences, making rewards available now seem much more valuable than larger rewards available later

- Threat response: Tasks associated with potential failure, criticism, or self-esteem threat activate the amygdala's threat detection system, triggering avoidance similar to fear responses

- Habit formation: Repeated patterns of avoidance become encoded as automatic responses, making procrastination increasingly habitual and difficult to interrupt

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Decision-Making Control Center

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is located in the front portion of the brain, behind the forehead, and is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions that distinguish human thinking from that of other animals. These executive functions include planning and organizing complex behaviors, decision-making that considers multiple factors and time horizons, self-control and impulse regulation, abstract reasoning about future consequences, and the maintenance of goals and intentions over time. In essence, the prefrontal cortex is the "executive" part of your brain that should theoretically keep the impulsive limbic system in check, overriding immediate impulses in service of longer-term objectives and deeper values.

When functioning optimally, the prefrontal cortex helps you assess your goals realistically, weigh the consequences of different actions across time, resist immediate temptations that conflict with your stated priorities, and maintain focus on tasks that serve your long-term interests even when they're not immediately rewarding. It's the voice in your head that says "I should work on that project" when the limbic system is saying "Let's check social media instead."

However, the prefrontal cortex has significant limitations that make it vulnerable to being overridden:

- Cognitive load sensitivity: The PFC can be easily overwhelmed by stress, fatigue, hunger, information overload, or emotional distress, all of which reduce its capacity to exert self-control

- Resource depletion: Self-control appears to function somewhat like a muscle that can be fatigued through use, meaning willpower may be depleted after exercising it repeatedly

- Evolutionary recency: The PFC is the most recently evolved part of the brain and is less powerful in moment-to-moment competition with the evolutionarily older limbic system

- Abstraction limitations: Future consequences are represented abstractly in the PFC, making them feel less real and compelling than the concrete, immediate experiences driven by the limbic system

- Task aversion amplification: When tasks seem overwhelming, confusing, or associated with negative emotions, the PFC may actually contribute to avoidance by generating rationalizations for delay

When the prefrontal cortex becomes overwhelmed or depleted—as it commonly does in our demanding, information-saturated modern world—the limbic system effectively takes the steering wheel, pushing you toward procrastination by suggesting more immediately enjoyable activities that provide instant emotional relief at the cost of future stress.

Dopamine and Procrastination

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Procrastination is also fundamentally influenced by the brain's dopamine system, which serves as the neurochemical foundation of motivation, reward anticipation, and learning from outcomes. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, motivation, and the anticipation of rewards—it's not simply the "pleasure chemical" as popularly believed, but more accurately the "motivation chemical" that drives us toward activities the brain predicts will be rewarding.

When you engage in enjoyable activities—such as watching an entertaining video, receiving a social media notification, eating something delicious, or winning a game—your brain releases dopamine, which creates a pleasurable feeling and, importantly, reinforces the behavior by strengthening neural pathways that make you more likely to seek out similar activities in the future. The brain essentially learns: "That activity predicted reward; do more of that."

The dopamine system contributes to procrastination in several important ways:

- Reward prediction: Tasks perceived as boring, difficult, or stressful generate less dopamine anticipation, making them feel unmotivating before you even begin

- Immediate vs. delayed rewards: Dopamine responds much more strongly to immediate rewards than to rewards expected in the distant future, even if the future rewards are objectively larger

- Novelty seeking: Dopamine is released in response to novelty and unpredictability, which is why checking email or social media (with their variable reward schedules) is so compelling compared to predictable work tasks

- Negative prediction errors: When a task turns out to be more difficult or less rewarding than expected, dopamine levels actually decrease below baseline, creating an aversive experience that discourages future engagement

- Habit loop formation: Activities that provide consistent dopamine hits become increasingly automatic and difficult to resist, while behaviors that don't provide dopamine rewards require increasing effort to initiate

This creates a vicious cycle: the more you procrastinate by engaging in immediately rewarding distractions, the stronger those distraction pathways become and the weaker the pathways associated with productive work become. Your brain literally reshapes itself to make procrastination easier and work initiation harder.

The Psychological Drivers of Procrastination

While brain chemistry and neural architecture play crucial roles in procrastination, psychological factors operating at the level of thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and personality also contribute substantially to why we delay tasks. Understanding these underlying psychological drivers can help explain why some people procrastinate more severely than others, why certain tasks are more likely to be put off, and what interventions might be most effective for different individuals.

Fear of Failure (or Success)

One of the most common and powerful psychological drivers of procrastination is the fear of failure—the anxiety that accompanies tasks where there is a possibility of falling short, being judged negatively, or confirming fears of inadequacy. When you're faced with a task that feels challenging, high-stakes, or evaluative, the fear of not measuring up can become paralyzing. This fear generates anxiety and emotional discomfort, which in turn triggers the avoidance response. You delay starting the task because avoiding the possibility of failure feels better in the short term than facing the discomfort of trying and potentially falling short.

Procrastination is, in essence, self-harm. When we procrastinate, we're not just avoiding a task—we're avoiding the emotions we associate with the task. We sacrifice our future well-being to relieve present discomfort, even when we know intellectually that we're making things worse.

— Dr. Fuschia Sirois

The fear of failure is particularly insidious because it often operates beneath conscious awareness. The procrastinator may not consciously think "I'm afraid of failing," but instead generates rationalizations: "I work better under pressure," "I need to do more research first," "I'll start when I'm in the right mood." These rationalizations protect the ego from having to confront the underlying fear while enabling continued avoidance.

Interestingly, some people also procrastinate due to a fear of success, which manifests through several concerns:

- Increased expectations: Success might raise the bar for future performance, creating pressure to maintain or exceed that level indefinitely

- Visibility and scrutiny: Achievement might attract attention, evaluation, and criticism that feel threatening

- Identity disruption: Success might require changing self-concept from someone who struggles to someone who succeeds, which can feel unfamiliar and threatening

- Relationship concerns: Success might create distance from peers, family members, or communities where achievement is not valued or is actively discouraged

- Responsibility expansion: Success might lead to increased responsibilities, demands, and obligations that feel overwhelming to contemplate

In both cases—fear of failure and fear of success—procrastination serves as a defense mechanism to protect against perceived psychological threats, even though the protection comes at substantial cost.

Perfectionism

Perfectionism is another major psychological driver of procrastination, though the relationship is more complex than it might initially appear. Perfectionists often set impossibly high standards for themselves and their work, standards that virtually guarantee some degree of falling short. This creates a painful bind: the perfectionist deeply wants to produce excellent work, but the fear of producing anything less than excellent makes it terrifying to begin or to finish (and therefore expose the work to evaluation).

Perfectionism contributes to procrastination through multiple pathways:

- Paralysis by standards: The gap between current capability and ideal outcome feels so vast that beginning seems pointless

- Preparation trap: The perfectionist convinces themselves they need more time, more research, more planning, better conditions before they can begin, leading to indefinite delay

- All-or-nothing thinking: If perfect isn't possible right now, then why bother at all? This cognitive distortion makes partial progress feel worthless

- Completion avoidance: Even when work is substantially done, perfectionists may delay finishing and submitting because completion means exposure to judgment

- Comparison paralysis: Comparing oneself to idealized standards or highly accomplished others makes one's own potential efforts seem inadequate before they begin

Ironically, perfectionism typically leads to lower productivity and poorer performance in the long run than a more forgiving approach would achieve. The pressure to be perfect makes it difficult to take the first step, to accept "good enough" when good enough is appropriate, or to finish tasks in a timely manner. The perfectionist who delays often ends up producing rushed, suboptimal work under deadline pressure—the exact outcome their perfectionism was meant to prevent.

Present Bias and Time Inconsistency

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Humans are naturally inclined to value immediate rewards over future benefits, a universal tendency known as present bias or hyperbolic discounting. This is why watching an entertaining show right now feels more appealing than working on a project due next week, even when you intellectually understand that the project is more important and that delay will cause stress. We systematically discount future rewards and future consequences, making them feel less real, less compelling, and less motivating than present experiences.

Time inconsistency is a related phenomenon that explains the puzzling gap between our intentions and our actions over time. It refers to the conflict between your present self (who wants to avoid discomfort and seek immediate pleasure) and your future self (who will have to deal with the accumulated consequences of procrastination). When you make plans for the future—"I'll start that project on Saturday"—you're imagining your future self as someone with different preferences than your present self, someone who will be willing to work rather than relax. But when Saturday arrives, you're back to being a present self who prefers immediate pleasure, and the plan dissolves.

Time inconsistency manifests in procrastination through several patterns:

- Optimistic planning: Assuming future-self will be more motivated, less tired, and better positioned to do the work than present-self

- Present-self dominance: In any given moment, present-self makes the actual decisions, and present-self consistently prefers comfort

- Deadline illusion: Distant deadlines don't feel real or urgent, so the motivation to act doesn't activate until the deadline approaches

- Cost-benefit shifting: The costs of work (effort, discomfort) are felt immediately, while the benefits are abstract and future-oriented

- Regret accumulation: Future-self inherits the consequences of present-self's choices but has no voice in making those choices

Understanding time inconsistency helps explain why we can sincerely intend to stop procrastinating, create detailed plans for behavior change, and still find ourselves procrastinating again when the moment of action arrives. The person making the plan and the person who must execute it are, in a meaningful psychological sense, different people with different priorities.

Task Aversion and Emotional Regulation

Procrastination is fundamentally an emotional response to tasks we find unpleasant, boring, overwhelming, confusing, or emotionally threatening. This phenomenon, known as task aversion, recognizes that procrastination isn't primarily about time management or organization but about emotion management. When you feel negatively about a task—whether due to its inherent difficulty, its monotony, the anxiety it provokes, or the pressure associated with it—your brain naturally wants to avoid the discomfort by finding something more enjoyable or at least less unpleasant to do.

Viewed through this lens, procrastination becomes a form of short-term emotional regulation—a way of managing uncomfortable feelings in the present moment by avoiding their source. Instead of addressing the negative emotions constructively by engaging with the task and working through the discomfort, you avoid the task altogether, seeking short-term emotional relief through distraction, pleasure, or simply thinking about something else.

The procrastinator is not fundamentally different from anyone else. We all prefer pleasure to pain, comfort to discomfort. The procrastinator simply has not developed effective strategies for tolerating the discomfort of getting started on tasks they'd rather avoid.

— Dr. Joseph Ferrari

Task aversion and the use of procrastination for emotional regulation involve several components:

- Mood repair motivation: Procrastination temporarily improves mood by removing the source of negative emotion from immediate awareness

- Avoidance conditioning: Successful mood repair reinforces avoidance, making it more likely in the future

- Emotional buildup: Avoided tasks don't disappear; they accumulate anxiety, guilt, and urgency over time, making eventual engagement even more aversive

- Tolerance deficit: Regular use of avoidance prevents development of emotional tolerance skills that would make task engagement easier

- Identity formation: Over time, procrastinators may come to see themselves as people who can't handle certain tasks, further reducing engagement

Lack of Motivation or Purpose

A lack of intrinsic motivation or clear purpose can substantially fuel procrastination, particularly for tasks that feel externally imposed rather than personally meaningful. When you don't see genuine value, meaning, or connection to your goals in a task, it becomes considerably harder to generate the motivation to start or persist. This is particularly true for tasks imposed by external factors—a work assignment you're not passionate about, a school project that doesn't align with your interests, administrative tasks that feel meaningless—where there's no internal drive or emotional connection to provide natural motivation.

Motivational deficits contribute to procrastination through several pathways:

- Purpose vacuum: Without clear "why" for doing a task, the effort required seems disproportionate to any benefit

- Autonomy undermining: Tasks that feel controlled or coerced rather than chosen generate resistance and avoidance

- Values misalignment: Work that conflicts with personal values or identity creates motivation-sapping dissonance

- Competence doubts: Uncertainty about ability to do the task successfully undermines motivation to try

- Connection absence: Tasks that seem disconnected from relationships, community, or anything meaningful feel hollow

When intrinsic motivation is absent and external motivation (deadlines, consequences) is distant, procrastination naturally fills the gap as the brain searches for more engaging, meaningful, or rewarding activities to pursue instead.

The Impact of Procrastination on Mental Health and Relationships

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Procrastination doesn't just affect your productivity, your grades, or your career advancement—it can profoundly impact your mental health, your physical well-being, and your relationships with others. The consequences of chronic procrastination extend far beyond missing deadlines or feeling temporarily stressed; they can significantly and cumulatively affect your emotional well-being, your self-concept, your health behaviors, and how you interact with the people who matter most to you.

Increased Stress and Anxiety

Procrastination is closely and bidirectionally linked to increased levels of stress and anxiety in a relationship that feeds on itself over time. While procrastination temporarily relieves anxiety by removing the aversive task from immediate awareness, it ultimately increases anxiety as deadlines approach and the pressure to complete tasks builds exponentially. The longer you delay a task, the more anxious you typically feel about it, both because the deadline is closer and because the accumulated delay itself becomes a source of stress and self-criticism.

The stress-procrastination cycle operates through several mechanisms:

- Deadline pressure amplification: As deadlines approach with work unfinished, stress hormones flood the system, impairing the very cognitive functions needed for productive work

- Background anxiety: Even when not actively thinking about procrastinated tasks, they create a constant low-level anxiety that drains mental resources and reduces well-being

- Catastrophic thinking: Delay provides time for imagining worst-case scenarios, which amplifies anxiety about the task and its potential consequences

- Rumination loops: Procrastinators often spend substantial time thinking about the tasks they're avoiding, creating mental exhaustion without making progress

- Sleep disruption: Anxiety about procrastinated tasks interferes with sleep quality, which further impairs cognitive function and self-regulation

- Guilt compounding: Each day of continued delay adds another layer of guilt and self-criticism, making the emotional load heavier

Chronic procrastinators often experience ongoing, elevated anxiety as a result of their delays, which impacts sleep quality, mood stability, and overall quality of life. This chronic stress state can contribute to burnout, making it even harder to break free from procrastination patterns because the depleted state reduces the self-regulatory capacity needed to override avoidance impulses.

Impact on Self-Esteem and Confidence

Procrastination can significantly erode self-esteem and confidence over time, creating lasting damage to self-concept that extends far beyond any individual delayed task. When you repeatedly fail to follow through on your own intentions, miss deadlines you set for yourself, break promises to yourself about when you'll start or finish projects, you internalize a narrative about yourself as someone who is unreliable, undisciplined, or fundamentally incapable.

The self-esteem erosion process involves several components:

- Self-trust breakdown: Each instance of procrastinating despite intentions not to erodes trust in your own word to yourself

- Identity confirmation: Procrastination confirms and strengthens an identity as "a procrastinator," making the behavior feel more inherent and unchangeable

- Shame accumulation: Repeated procrastination generates shame about the behavior itself, which ironically increases avoidance through shame-driven withdrawal

- Capability doubts: Inability to make yourself do tasks leads to questioning whether you're capable of doing them at all

- Comparison suffering: Seeing others accomplish tasks you've delayed exacerbates feelings of inadequacy and failure

- Achievement gap: Procrastination prevents accomplishments that would build genuine self-esteem through mastery and contribution

Low self-esteem and procrastination often become locked in a self-reinforcing cycle where each feeds the other. The procrastination damages self-esteem, the damaged self-esteem makes future tasks feel more threatening and avoidance more tempting, and the increased procrastination further damages self-esteem.

Strained Relationships

Procrastination can strain and damage personal and professional relationships in ways that procrastinators often fail to anticipate or fully appreciate. In professional environments, procrastination can lead to missed deadlines that affect team projects, poor-quality work that reflects badly on collaborative efforts, and visible failures that frustrate colleagues, supervisors, and clients. This damages trust, reputation, and working relationships, sometimes permanently.

Relationship damage from procrastination manifests in numerous ways:

- Broken promises: Commitments that aren't kept erode trust and communicate that the relationship isn't a priority

- Burden shifting: When procrastinators don't complete their share, others must compensate, breeding resentment

- Disappointment accumulation: Repeated letdowns create patterns of lowered expectations and emotional distance

- Conflict avoidance spiraling: Procrastinating difficult conversations allows problems to fester and grow more serious

- Emotional unavailability: The mental preoccupation with procrastinated tasks and associated guilt reduces presence and connection in relationships

- Modeling effects: Procrastination behaviors can be observed and adopted by children, partners, or colleagues

In personal relationships, procrastination may manifest as avoiding difficult but necessary conversations, delaying commitments that matter to partners or family members, failing to follow through on promises or plans, or neglecting relationship maintenance that keeps connections healthy. Partners and family members of chronic procrastinators often report feeling deprioritized, frustrated, and unable to rely on the procrastinator, which gradually erodes intimacy and trust.

Breaking the Cycle of Procrastination: Practical Strategies

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Now that we have thoroughly explored the psychological and neurological underpinnings of procrastination, understanding both why we delay and the substantial costs of doing so, the essential next step is implementing actionable strategies to overcome procrastination and build healthier, more productive patterns of engaging with our responsibilities and goals. While breaking the procrastination habit is genuinely challenging—you're working against millions of years of evolved brain architecture and potentially years or decades of conditioned avoidance—it is absolutely possible with the right strategies, sufficient self-compassion, and sustained commitment to change.

Practice Time Management and Break Tasks into Smaller Steps

One of the most effective and immediately applicable strategies for combating procrastination is to break large, overwhelming tasks into smaller, more manageable components that feel less threatening and more achievable. Large tasks naturally trigger overwhelm, which activates the avoidance response and makes starting feel impossible. By breaking a project into smaller, concrete, actionable steps, you reduce the psychological barrier to beginning and make it possible to build momentum through small wins.

Effective task decomposition involves several principles:

- Identify the next physical action: Rather than thinking about "the project," identify the single next concrete step—"open document," "write first sentence," "make list of research sources"

- Make steps small enough to be non-threatening: Each step should feel achievable without significant effort or willpower, reducing the activation energy required to begin

- Create clear completion criteria: Vague tasks invite avoidance; specific, bounded tasks allow for the satisfaction of completion

- Sequence appropriately: Arrange steps in logical order that builds toward completion while maintaining momentum

- Celebrate micro-completions: Acknowledge and appreciate progress, however small, to activate the reward system and reinforce engagement

Time management techniques like the Pomodoro Technique can also help maintain focus and create structure that supports engagement. The Pomodoro Technique involves working in focused intervals (traditionally 25 minutes) followed by short breaks (5 minutes), with longer breaks after every four intervals. This method creates urgency without overwhelming, provides regular recovery periods, and makes work feel bounded and manageable rather than endless.

Address Underlying Emotions and Practice Self-Compassion

Since procrastination is fundamentally an emotional response to aversive tasks—a form of mood regulation through avoidance—addressing the underlying emotions directly is essential for sustainable change. Rather than fighting against procrastination through willpower alone, which is exhausting and often unsuccessful, work with the emotional dimension of the problem by developing healthier ways of relating to difficult feelings.

Emotional approaches to procrastination include:

- Emotion recognition: Notice and name the emotions that arise when facing procrastinated tasks—anxiety, boredom, fear, overwhelm, confusion

- Acceptance rather than avoidance: Practice allowing uncomfortable emotions to be present without needing to escape them, recognizing they're temporary and survivable

- Curiosity about emotions: Rather than treating negative emotions as enemies to flee, approach them with curiosity about what they're communicating

- Self-compassion application: Treat yourself with the same kindness you would offer a friend struggling with the same difficulties

- Emotional reframing: Reinterpret the meaning of difficult emotions—anxiety might indicate that the task matters, boredom might be a passing state, fear might signal growth opportunity

Self-compassion is particularly important because procrastination often triggers harsh self-criticism that paradoxically makes procrastination more likely rather than less. Research by Dr. Fuschia Sirois and others has shown that self-compassion—treating yourself with kindness rather than harsh judgment when you procrastinate—actually reduces future procrastination, while self-criticism increases it. This happens because self-criticism adds another layer of negative emotion to an already aversive situation, making avoidance more tempting, while self-compassion creates emotional safety that makes engagement possible.

Set Clear Goals and Prioritize Effectively

Setting clear, specific, meaningful goals can significantly help overcome procrastination by providing direction, motivation, and criteria for progress. Vague intentions like "work on project" or "be more productive" provide insufficient guidance for action and insufficient motivation for effort. Clear goals, in contrast, make it obvious what needs to be done, create the possibility of measurable progress, and connect daily tasks to larger purposes that provide meaning.

Effective goal-setting for procrastination involves several principles:

- Specificity: Goals should be concrete and actionable—"write 500 words of introduction" rather than "work on paper"

- Measurability: Progress should be observable and quantifiable so you can see yourself advancing

- Achievability: Goals should be challenging but realistic given your current capacity and circumstances

- Relevance: Goals should connect to larger values and purposes that provide intrinsic motivation

- Time-boundedness: Goals should have deadlines or time limits that create urgency and prevent indefinite drift

- Process focus: Focus on controllable process goals (hours worked, pages written) rather than outcome goals (grade received, promotion awarded) that depend on factors beyond your control

Prioritization is equally crucial, as not all tasks deserve equal attention and trying to do everything often results in doing nothing effectively. Methods like the Eisenhower Matrix help categorize tasks based on their urgency (how soon they must be done) and importance (how much they matter to your goals and values). By consistently focusing on high-importance tasks rather than being driven by urgency alone, you reduce the accumulated backlog that makes procrastination overwhelming.

Create a Productive Environment

Your environment plays a significant and often underappreciated role in procrastination by either supporting focused engagement or constantly tempting you toward distraction. In our technology-saturated world, distractions are more accessible, more compelling, and more perfectly designed to capture attention than ever before. Smartphones, social media, streaming entertainment, and countless other diversions are engineered by some of the world's smartest people to be maximally engaging and difficult to resist.

Environment optimization strategies include:

- Physical workspace design: Create a dedicated work area that's associated with productive work, not leisure or distraction

- Digital distraction removal: Use website blockers, app limiters, phone-away techniques, or separate devices for work versus entertainment

- Notification elimination: Turn off non-essential notifications that interrupt focus and tempt task-switching

- Temptation distance: Increase the friction required to access distractions (phone in another room, logged out of social media) while decreasing friction for productive activities

- Environmental cues: Use visual or other cues that remind you of your goals, priorities, and the person you want to become

- Social environment: Surround yourself with people who support your goals and model productive behavior

Remember that willpower is a limited resource that depletes with use. Rather than relying on willpower to resist a tempting environment, design your environment to make the productive choice the easy choice and the procrastination choice the difficult one.

Use Positive Reinforcement and Reward Systems

Author: Marcus Reed;

Source: psychology10.click

Reward yourself for completing tasks, including small milestones and steps along the way. Positive reinforcement helps activate the brain's reward system—the same system that makes procrastination tempting—and redirects it to support productive behavior. By associating positive experiences with task completion rather than task avoidance, you can gradually retrain your brain's motivation patterns.

Effective reward strategies include:

- Immediate rewards: Provide small rewards immediately upon task completion to create clear contingency between work and pleasure

- Proportionate rewards: Match reward size to task difficulty so that larger challenges receive larger rewards

- Meaningful rewards: Choose rewards you genuinely enjoy rather than things you think you "should" want

- Variety: Vary rewards to prevent habituation and maintain their motivating power

- Natural rewards: Learn to appreciate the intrinsic rewards of completion—relief, pride, momentum, reduced anxiety

- Social rewards: Share accomplishments with others who will celebrate them with you

The goal is to change the emotional equation so that task completion becomes associated with positive feelings that compete with the immediate gratification of procrastination.

FAQ

Procrastination is far more than a simple bad habit or character flaw—it is a complex psychological and neurological process influenced by the brain's evolved preference for immediate gratification, the challenges of emotional regulation when facing aversive tasks, the cognitive limitations of the prefrontal cortex, and the psychological dynamics of fear, perfectionism, and purpose. While procrastination may offer genuine short-term emotional relief, it ultimately leads to increased stress, accumulated guilt, eroded self-esteem, damaged relationships, and a widening gap between the life you're living and the life you want to create.

The good news emerging from decades of research is that procrastination is not a fixed trait or an inevitable destiny. It is a pattern of behavior that, like any pattern, can be understood, interrupted, and replaced with more effective alternatives. By understanding the neurological and psychological mechanisms behind why we procrastinate, we gain insights that transform an adversary into a puzzle that can be solved. By implementing practical strategies—breaking tasks into smaller steps, addressing underlying emotions with self-compassion, setting clear and meaningful goals, designing supportive environments, and building reward systems that reinforce productive behavior—you can gradually overcome the cycle of delay and build healthier, more productive habits that serve your authentic goals and values.

Breaking free from procrastination requires patience with yourself, persistence through setbacks, and recognition that change happens gradually rather than all at once. You are working against powerful brain systems and potentially years of conditioned patterns, so instant transformation is unrealistic. But with sustained effort, appropriate strategies, and self-compassion for the journey, meaningful change is absolutely achievable. By taking control of your procrastination tendencies, you improve not only your productivity and accomplishments but also your emotional well-being, your self-trust, your stress levels, and the health of your relationships—creating a life that reflects your intentions and capabilities rather than your avoidance patterns.

The first step, appropriately enough, is to begin. Not perfectly, not completely, not with absolute confidence—just to begin, right now, with whatever small step you can take toward the task you've been avoiding. Your future self will thank you.

This article provides general information about the psychology of procrastination and is not intended as professional psychological advice. If you are experiencing chronic procrastination that significantly impacts your work, relationships, or quality of life, consider consulting with a psychologist or therapist who specializes in behavioral issues for personalized assessment and treatment.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.