Mind Games: The Role of Self-Deception in Everyday Decision Making

Mind Games: The Role of Self-Deception in Everyday Decision Making

Content

Content

Have you ever found yourself justifying a decision you knew deep down was wrong? Have you excused behavior that contradicted your core values, convinced yourself that a problem didn't exist when evidence clearly suggested otherwise, or clung to a belief about yourself or your situation that you secretly suspected wasn't true? If so, you've encountered self-deception—one of the most fascinating, pervasive, and consequential phenomena in human psychology.

Self-deception is far more common than most people realize, and it plays a profound role in virtually every aspect of our lives. From the small daily choices we make about how to spend our time and money to the life-altering decisions about careers, relationships, health, and personal identity, self-deception shapes how we perceive situations, interpret information, interact with others, and navigate the complex landscape of human existence. It influences everything from hitting the snooze button for the fifth time while telling yourself you'll definitely get up early tomorrow, to staying in an unfulfilling job or toxic relationship while convincing yourself that things aren't really that bad.

But why do we deceive ourselves? What psychological purposes does this seemingly irrational behavior serve? And how does this internal trickery affect our ability to make sound decisions, build authentic relationships, and live lives aligned with our true values and aspirations? Understanding self-deception is not merely an academic exercise—it's essential for anyone seeking greater self-awareness, better decision-making, and more authentic engagement with life.

In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the psychology of self-deception, examine its evolutionary origins and psychological drivers, explore its role in everyday decision-making across multiple life domains, and discuss how becoming more aware of our tendencies to self-deceive can lead to better choices, healthier relationships, and greater alignment between our actions and our values.

What is Self-Deception?

Self-deception is a complex psychological phenomenon where individuals hold conflicting beliefs or desires and unconsciously manipulate information to maintain a preferred belief, often by distorting, ignoring, or selectively attending to certain facts. It involves a type of mental gymnastics where one part of the mind effectively lies to another, allowing people to believe falsehoods that protect their sense of self, preserve self-esteem, reduce anxiety, or maintain comfortable illusions about themselves and their world.

Unlike simple error or ignorance, self-deception involves some level of awareness—however buried or implicit—that what one believes is not accurate. The self-deceiver simultaneously knows and doesn't know the truth, holding contradictory beliefs in different compartments of the mind. This paradoxical quality has made self-deception a subject of intense philosophical debate and psychological investigation for centuries.

The Dual Nature of Self-Deception

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Self-deception is distinct from ordinary lying in that it operates on two levels simultaneously within the same mind:

The Deceiver: One part of the mind actively distorts information, omits inconvenient facts, creates convincing rationalizations, or directs attention away from threatening truths. This process often operates below conscious awareness, automatically protecting the individual from information that would cause psychological distress.

The Deceived: Another part of the mind accepts these distortions as truth, incorporating them into the person's conscious beliefs and self-concept, even when at some deeper level the person "knows" they are misleading themselves. This part experiences the false belief as genuine conviction.

This dual nature is what makes self-deception so powerful, pervasive, and difficult to overcome. Unlike straightforward lying to others, where we consciously know the truth and deliberately choose to misrepresent it, self-deception allows us to obscure the truth from ourselves, making it significantly easier to maintain comfortable illusions and justify decisions that may be harmful in the long run.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. We are all susceptible to self-deception, and the sophisticated mind is often the most skilled at constructing elaborate justifications for what it wants to believe.

— Richard Feynman

Forms of Self-Deception

Self-deception manifests in numerous forms, each serving slightly different psychological functions:

Rationalization: Creating seemingly logical justifications for actions, beliefs, or feelings that actually stem from other, often less acceptable, motives. The rationalizing mind constructs post-hoc explanations that make behavior appear reasonable, even when the true motivations are emotional, self-serving, or irrational.

Minimization: Downplaying the significance, frequency, or severity of a problem, negative behavior, or unflattering truth. Minimization allows us to acknowledge something partially while reducing its apparent importance enough that we don't have to change or confront it fully.

Denial: Refusing to acknowledge or accept uncomfortable truths, even when presented with clear evidence. Denial represents perhaps the most complete form of self-deception, where the threatening information is rejected entirely rather than merely reinterpreted or minimized.

Selective Attention: Focusing on information that supports a desired belief while systematically ignoring, discounting, or failing to seek out contradictory evidence. This creates a biased information environment that makes self-deception easier to maintain.

Overconfidence: Systematically overestimating one's abilities, knowledge, or the probability of positive outcomes while underestimating risks, challenges, or the likelihood of negative consequences. This form of self-deception can lead to poor decisions and excessive risk-taking.

Projection: Attributing one's own unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or motivations to others rather than acknowledging them in oneself. Projection allows us to recognize something without owning it.

Compartmentalization: Keeping contradictory beliefs, values, or aspects of life separate so that they don't come into direct conflict. This allows maintaining inconsistent positions without experiencing the discomfort of their contradiction.

What is Self-Deception

The Evolutionary Roots of Self-Deception

While self-deception may seem irrational—why would evolution favor a tendency to believe false things about ourselves and our world?—it has deep evolutionary roots and may have provided significant adaptive advantages in our ancestral environment. Understanding these evolutionary origins helps explain why self-deception is so universal and so resistant to simple correction.

Self-Deception as a Social Tool

One influential theory, developed by evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers, suggests that self-deception evolved primarily as a tool for social manipulation. The argument is elegant: if you can convince yourself that you're more competent, attractive, trustworthy, or morally superior than you actually are, you become better equipped to convince others of these qualities as well. Sincere belief is more convincing than conscious deception because it eliminates the subtle cues—hesitation, inconsistency, physiological signs of stress—that might reveal a deliberate lie.

This phenomenon, closely related to the self-enhancement bias, provides measurable social benefits. People who genuinely believe in their own competence project more confidence and assertiveness. This confidence, in turn, can attract romantic partners, secure social alliances, enhance leadership effectiveness, and improve competitive outcomes. In the social competition that characterized human evolution, those who could self-deceive effectively may have gained significant advantages in status, reproduction, and survival.

Evolutionary advantages of self-deception include:

- Enhanced persuasion: Sincere belief is more convincing than conscious lying

- Increased confidence: Self-enhancement improves social presence and influence

- Better first impressions: Positive self-beliefs create more favorable initial interactions

- Stress reduction: Avoiding harsh truths reduces physiological stress responses

- Persistence enhancement: Optimistic self-beliefs support continued effort despite setbacks

- Social cohesion: Shared positive illusions can strengthen group bonds

Self-Deception as a Psychological Defense Mechanism

Another complementary theory positions self-deception as a psychological defense mechanism that evolved to protect individuals from overwhelming stress, anxiety, or despair. In situations where facing the full truth could be psychologically devastating—such as confronting one's mortality, accepting responsibility for serious harm, or acknowledging complete powerlessness—self-deception serves as a crucial coping strategy.

By distorting reality to make it more bearable, self-deception allows individuals to maintain psychological functioning, preserve their sense of self and agency, and avoid the potentially paralyzing effects of fear, shame, guilt, or hopelessness. In our evolutionary past, individuals who could maintain some degree of optimism and self-efficacy even in difficult circumstances may have been more likely to persist, adapt, and ultimately survive.

Defensive functions of self-deception:

- Terror management: Buffering awareness of mortality and existential threats

- Self-esteem maintenance: Protecting sense of worth and capability

- Hope preservation: Maintaining motivation in difficult circumstances

- Trauma buffering: Reducing immediate impact of overwhelming experiences

- Identity coherence: Preserving consistent sense of self despite contradictions

Why We Deceive Ourselves: The Psychological Drivers

Understanding why we deceive ourselves requires examining the powerful psychological forces that make self-deception so attractive and so automatic. Several key factors drive our tendency to engage in self-deception, each serving distinct psychological functions while often operating in combination.

Cognitive Dissonance: Resolving Internal Conflict

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

One of the primary drivers of self-deception is cognitive dissonance—the psychological discomfort experienced when holding two conflicting beliefs, when behavior contradicts values, or when new information challenges existing convictions. This dissonance creates an unpleasant state of mental tension that the mind is strongly motivated to reduce.

To alleviate this discomfort, the mind often engages in self-deception, rationalizing behavior, reinterpreting situations, or adjusting beliefs to bring thoughts and actions into apparent alignment. The remarkable finding from decades of research is that people will often change their beliefs rather than their behavior—they deceive themselves about what they think rather than changing what they do.

Examples of dissonance-driven self-deception:

- A smoker who convinces themselves that the health risks are exaggerated

- Someone who considers themselves honest but cheated, convincing themselves it wasn't really cheating

- A person who values environmental sustainability but drives a gas-guzzling car, minimizing their environmental impact

- Someone who bought an expensive item they couldn't afford, convincing themselves it was necessary

A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies, becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else. The self-deceiver loses the ability to distinguish between genuine feeling and manufactured sentiment.

— Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ego Preservation: Protecting Self-Esteem

The desire to maintain a positive self-image is perhaps the most powerful motivator for self-deception. Humans have a profound need to think well of themselves—to see themselves as competent, moral, likable, and in control. When faced with evidence that threatens this positive self-concept, the mind often engages in self-deception rather than accepting an unflattering truth.

This ego-protective function operates constantly, filtering our interpretations of events, our memories of past behavior, and our expectations for the future. We take credit for successes while attributing failures to external circumstances. We remember our past behavior as more admirable than it actually was. We interpret ambiguous feedback in self-serving ways.

Ego-preservation mechanisms include:

- Self-serving attribution: Taking credit for success, blaming external factors for failure

- Positive memory bias: Remembering past actions more favorably than warranted

- Downward comparison: Comparing ourselves to those doing worse rather than better

- Selective feedback interpretation: Reading ambiguous feedback as positive

- Excuse generation: Creating explanations that protect self-image

Wishful Thinking: Clinging to Desired Beliefs

Self-deception is also fueled by wishful thinking—believing something because we want it to be true rather than because evidence supports it. This type of self-deception is emotionally driven; the desired belief feels good, while the alternative would be painful, frightening, or disappointing.

Wishful thinking is particularly common in areas of high emotional investment: personal relationships, health concerns, financial decisions, and cherished goals. Someone in a troubled relationship may convince themselves that their partner will change despite repeated evidence to the contrary. Someone with worrying symptoms may convince themselves it's nothing serious to avoid the anxiety of medical investigation.

Areas prone to wishful thinking:

- Relationships: Believing a partner will change or that incompatibilities don't matter

- Health: Minimizing symptoms or believing unhealthy behaviors won't have consequences

- Finances: Believing investments will recover or that spending isn't problematic

- Career: Believing opportunities will materialize without necessary action

- Goals: Believing desired outcomes are more likely than probability suggests

Confirmation Bias: Seeking Supporting Evidence

Confirmation bias—the tendency to seek out, interpret, favor, and remember information that confirms pre-existing beliefs while giving less attention to information that contradicts them—plays a crucial role in maintaining self-deception. This bias operates at every stage of information processing, creating a systematically distorted picture of reality.

Confirmation bias makes self-deception self-reinforcing. Once we've adopted a belief, we naturally encounter more "evidence" supporting it because we're looking for such evidence and interpreting ambiguous information in belief-consistent ways. This creates the subjective experience that our beliefs are well-supported even when they're not.

How confirmation bias supports self-deception:

- Selective exposure: Choosing information sources that confirm existing beliefs

- Biased interpretation: Reading ambiguous evidence as supporting preferred conclusions

- Differential scrutiny: Accepting confirming evidence uncritically while scrutinizing contradicting evidence

- Selective memory: Better remembering information that supports existing beliefs

- Biased questions: Asking questions likely to elicit confirming answers

Social Influence: Maintaining Harmony and Belonging

Self-deception can also be driven by social factors—the desire to maintain harmony in relationships, conform to group norms, preserve social standing, or avoid conflict. People may deceive themselves about their true feelings, opinions, or values to fit in, maintain relationships, or avoid the costs of social deviance.

This socially-driven self-deception can be subtle and may not even be recognized as self-deception. The person may genuinely come to believe the positions they've adopted for social reasons, forgetting or never fully acknowledging that these beliefs serve social functions rather than reflecting independent judgment.

Social drivers of self-deception:

- Conformity pressure: Adopting group beliefs to maintain belonging

- Relationship preservation: Deceiving oneself to avoid threatening important relationships

- Conflict avoidance: Convincing oneself of positions that prevent disagreement

- Status maintenance: Believing things that support one's social position

- Identity signaling: Adopting beliefs associated with desired group membership

The Role of Self-Deception in Everyday Decision-Making

Self-Deception in Everyday Decision.

Self-deception is not merely an abstract psychological concept studied in laboratories—it actively shapes how we make decisions, solve problems, evaluate options, and interact with others in our daily lives. Understanding how self-deception operates in specific domains can help us recognize it in our own lives and develop strategies for more honest decision-making.

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

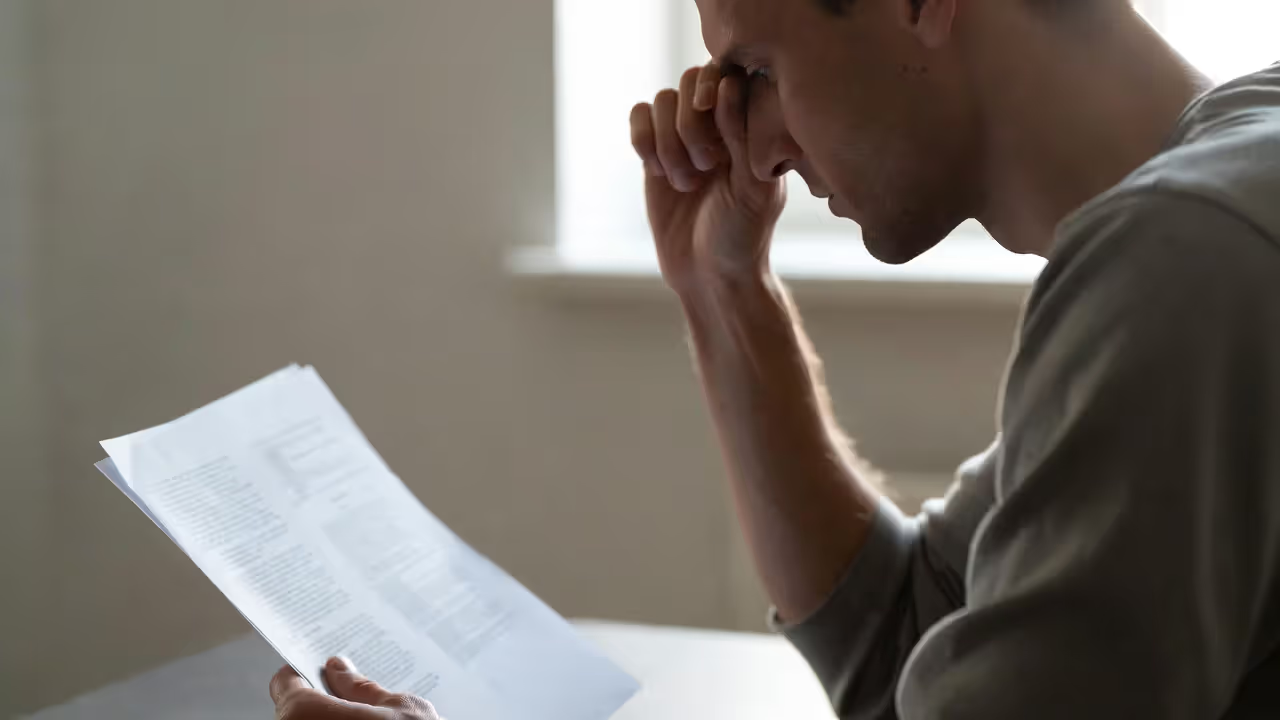

Personal Finance: Rationalizing Spending and Ignoring Consequences

Personal finance is one of the most common arenas for self-deception. People routinely deceive themselves about their spending habits, their financial situation, and the likely consequences of their choices. This self-deception allows immediate gratification while avoiding the psychological discomfort of facing financial reality.

Common financial self-deceptions:

- Convincing yourself that purchases are "needs" rather than "wants"

- Believing you'll "save more next month" while repeatedly not doing so

- Rationalizing expensive purchases as "investments" or "treating yourself"

- Minimizing the cumulative impact of small purchases

- Overestimating future income or underestimating future expenses

- Believing credit card debt is temporary and easily managed

- Convincing yourself that budgeting doesn't apply to your situation

The psychological mechanisms behind financial self-deception typically involve rationalization and minimization. The rationalizing mind creates justifications—"It was on sale, so I'm actually saving money," "I deserve this after working so hard," "I'll make up for it by cutting back elsewhere." Minimization allows ignoring the cumulative impact of decisions—each individual purchase seems insignificant even as they add up to serious financial problems.

Over time, this self-deception can lead to chronic financial instability, mounting debt, inadequate savings, and the stress and reduced life options that come with poor financial health. Breaking through financial self-deception often requires external intervention—confronting actual numbers, seeking feedback from others, or experiencing consequences severe enough to penetrate the self-protective fog.

Health and Fitness: Overestimating Effort and Minimizing Risks

Self-deception is remarkably prevalent in matters of health and fitness, where people consistently overestimate their healthy behaviors, underestimate their unhealthy ones, and minimize the risks associated with their lifestyle choices. This self-deception allows maintaining comfortable habits while preserving a self-image as someone who takes care of their health.

Health-related self-deceptions include:

- Overestimating exercise frequency, duration, or intensity

- Underestimating caloric intake and portion sizes

- Minimizing the health impact of "occasional" indulgences that are actually frequent

- Believing symptoms are minor and don't require medical attention

- Convincing oneself that unhealthy habits are temporary and easily changed

- Overestimating the healthiness of one's diet relative to actual eating patterns

- Believing genetic or lifestyle factors make one personally less susceptible to health risks

Research consistently shows significant gaps between people's beliefs about their health behaviors and their actual behaviors. Studies using objective measures find that people dramatically overestimate their physical activity and underestimate their caloric intake. This self-deception undermines health goals because people don't accurately assess their behavior and therefore don't make necessary adjustments.

Relationships: Ignoring Red Flags and Justifying Bad Behavior

In relationships—romantic, familial, and professional—self-deception can manifest as ignoring warning signs, justifying a partner's or colleague's problematic behavior, or convincing oneself that things will improve despite persistent evidence to the contrary. Relationship self-deception is often driven by powerful emotional investments and the pain that would come from acknowledging relationship problems.

Relationship self-deceptions include:

- Ignoring or minimizing red flags early in relationships

- Justifying a partner's hurtful behavior with excuses

- Convincing oneself that a partner will change despite repeated failures to do so

- Denying the severity of relationship problems

- Overestimating relationship satisfaction relative to objective indicators

- Believing one's own contribution to problems is smaller than it actually is

- Convincing oneself that staying in a bad relationship is better than alternatives

We lie loudest when we lie to ourselves, especially about our relationships. The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of—and self-deception ensures that we never have to examine those reasons too closely.

— Blaise Pascal

This self-deception keeps people stuck in relationships that don't serve them while preventing the honest communication and problem-solving that healthy relationships require. By deceiving themselves about their relationships' true state, people avoid the short-term pain of confrontation but accumulate long-term costs in unfulfillment, resentment, and wasted time.

Career Choices: False Contentment and Avoided Growth

Career decisions represent another domain where self-deception commonly operates. People may convince themselves they're satisfied with unfulfilling work, that their job is better than alternatives, or that circumstances prevent them from pursuing what they really want. This self-deception often serves to avoid the uncertainty, effort, and risk involved in career change.

Career-related self-deceptions:

- Convincing oneself of satisfaction with genuinely unfulfilling work

- Overestimating the risks of change and underestimating the costs of staying

- Believing external circumstances completely prevent pursuing desired paths

- Rationalizing failure to develop skills or pursue advancement

- Attributing lack of progress to external factors rather than own choices

- Convincing oneself that "passion" in work is unrealistic or unimportant

- Believing that current dissatisfaction is temporary and will resolve itself

This self-deception prevents people from pursuing opportunities that might align better with their values, interests, and capabilities, leading to years or even decades of quiet dissatisfaction punctuated by occasional recognition of what might have been.

Procrastination: The Deception of "Later"

Procrastination is often fundamentally powered by self-deception—the false belief that one's future self will be more motivated, more capable, more disciplined, or have more time than one's present self. This "temporal self-deception" allows avoiding immediate discomfort while maintaining the illusion that tasks will eventually be completed.

Procrastination self-deceptions:

- Believing "I'll feel more like doing it tomorrow"

- Convincing oneself there's plenty of time when deadlines approach

- Overestimating future motivation and underestimating future demands

- Believing small delays won't significantly impact outcomes

- Rationalizing avoidance as "waiting for the right moment"

- Convincing oneself that working under pressure produces better results

- Minimizing the stress and quality costs of last-minute work

The self-deceiving procrastinator has often repeated the same pattern many times—promising themselves they'll start earlier next time, experiencing the stress of last-minute work, recognizing the pattern, and then promptly forgetting this recognition when the next task arises. This cycle continues because self-deception prevents honest acknowledgment of one's actual behavioral patterns.

The Costs of Self-Deception: When Avoiding Truth Becomes Harmful

While self-deception can offer short-term psychological relief, social advantages, and protection from overwhelming distress, chronic or severe self-deception carries significant long-term costs. By systematically distorting reality, self-deception undermines decision-making quality, damages relationships, impedes personal growth, and creates a growing gap between how we live and how we might live if we faced truth more directly.

Poor Decision-Making and Accumulated Regret

When decisions are based on distorted beliefs, incomplete information, or false narratives, they're more likely to lead to suboptimal outcomes. Self-deception causes people to overestimate their abilities, underestimate risks, ignore important information, and make choices that conflict with their actual values and long-term interests.

Decision-making impairments from self-deception:

- Choices based on false assessments of abilities or circumstances

- Failure to adequately consider risks and downsides

- Ignoring information that would improve decision quality

- Pursuing goals that don't actually align with authentic values

- Repeating mistakes by failing to honestly assess past outcomes

- Making commitments based on unrealistic self-assessments

Over time, these compromised decisions accumulate into a life shaped more by self-deception than by authentic choice. The result is often regret—the recognition, usually arriving too late, that one's life has been shaped by beliefs that weren't true and choices that didn't reflect one's genuine priorities.

Stagnation and Missed Opportunities

Self-deception can trap people in unfulfilling situations—dead-end jobs, toxic relationships, unhealthy lifestyles, or limiting self-concepts—by preventing honest recognition of the situation and the possibilities for change. By deceiving themselves about the reality of their circumstances, people miss opportunities for growth, change, learning, and improvement.

Stagnation through self-deception:

- Staying in situations that don't serve genuine well-being

- Missing opportunities because of false beliefs about capabilities or options

- Failing to develop because of unwillingness to acknowledge weaknesses

- Avoiding challenges that would promote growth

- Settling for less than one's potential due to comfortable self-deceptions

- Losing years to situations that honest assessment would have motivated leaving

The person trapped by self-deception may not even recognize what they're missing. The self-deception that keeps them stuck also prevents them from seeing clearly the alternatives they're forgoing. Only in retrospect—or through external feedback—do they sometimes recognize the opportunities their self-deception caused them to miss.

Damaged Relationships and Lost Trust

In relationships, self-deception prevents the honest communication, genuine understanding, and effective conflict resolution that healthy connections require. When people deceive themselves about their feelings, needs, behaviors, or the state of their relationships, they cannot address underlying issues or build genuine intimacy.

Relationship damage from self-deception:

- Failure to address real issues because they're not honestly acknowledged

- Communication distorted by self-serving narratives

- Inability to receive feedback due to defensive self-deception

- Partners feeling unseen or misunderstood

- Conflict resolution impaired by unwillingness to acknowledge own contribution

- Trust erosion as self-deception eventually becomes apparent to others

Eventually, the self-deception that one person maintains affects others who must live with the consequences of decisions based on false beliefs. Partners, children, friends, and colleagues all bear costs when someone's self-deception shapes shared decisions or relationship dynamics.

Erosion of Self-Trust and Authentic Identity

Perhaps the most profound cost of chronic self-deception is the erosion of self-trust and authentic identity. When people habitually deceive themselves, they become progressively disconnected from their genuine emotions, desires, values, and beliefs. They lose touch with who they actually are beneath the layers of self-protective distortion.

Identity costs of self-deception:

- Disconnection from authentic feelings and desires

- Confusion about genuine values and priorities

- Difficulty trusting one's own judgment

- Sense of inner fragmentation or falseness

- Loss of access to intuition and genuine emotional signals

- Identity built on false beliefs rather than authentic self-knowledge

This disconnection creates a kind of inner loneliness—the experience of not really knowing oneself, of living a life that doesn't quite feel like one's own. Recovering from chronic self-deception requires not just seeing reality more clearly but rebuilding the relationship with oneself that self-deception has damaged.

Mind Games of Self-Deception

Self-Deception in Groups and Society

While we often think of self-deception as an individual phenomenon, it also operates powerfully at the level of groups, organizations, and entire societies. Collective self-deception can shape political movements, organizational cultures, and social beliefs in ways that affect millions of people.

Groupthink and Organizational Self-Deception

Organizations and groups are susceptible to collective forms of self-deception that can lead to catastrophic decisions. Groupthink—the tendency for cohesive groups to suppress dissent and converge on consensus without critical evaluation—represents a form of collective self-deception where uncomfortable truths are systematically excluded from group awareness.

Manifestations of organizational self-deception:

- Shared rationalizations: Groups develop collective justifications for questionable decisions

- Illusion of invulnerability: Organizations believe they're immune to risks that affect others

- Stereotyping outsiders: Critics and competitors are dismissed rather than seriously considered

- Self-censorship: Members suppress doubts to maintain group harmony

- Illusion of unanimity: Silence is interpreted as agreement, creating false consensus

- Mindguards: Some members actively protect the group from disconfirming information

Historical examples abound: the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Challenger space shuttle disaster, corporate collapses like Enron—in each case, collective self-deception prevented groups from acknowledging warnings and making realistic assessments.

Political and Ideological Self-Deception

Political beliefs and ideological commitments create powerful conditions for self-deception. People systematically process political information in biased ways, accepting claims that support their side while critically scrutinizing claims from the opposition. This partisan self-deception allows maintaining confident political beliefs despite the complexity and uncertainty of most political questions.

Political self-deception patterns:

- Accepting favorable information uncritically while demanding impossible standards of proof for unfavorable information

- Attributing positive outcomes to one's own party and negative outcomes to opponents

- Believing one's own political views are based on facts while opponents are driven by bias

- Selective exposure to media that confirms existing political beliefs

- Interpreting identical behaviors differently depending on who performs them

This ideological self-deception contributes to political polarization, making constructive dialogue across differences increasingly difficult as each side maintains inflated confidence in positions that honest assessment might complicate.

Cultural and Societal Self-Deception

Entire societies can engage in collective self-deception about their history, their present circumstances, or their likely future. National myths, cultural narratives, and shared assumptions often contain elements of self-deception that serve psychological functions—preserving national pride, maintaining social cohesion, or avoiding collective guilt—while distorting understanding of reality.

Examples of societal self-deception:

- Sanitized historical narratives that minimize past wrongs

- Beliefs in national exceptionalism that ignore evidence of ordinary limitations

- Collective denial of ongoing social problems

- Shared optimism bias about environmental or economic futures

- Cultural assumptions that resist evidence challenging them

Addressing societal self-deception is particularly challenging because the distorted beliefs are reinforced by social consensus—everyone around you shares the same self-deception, making it feel like obvious truth rather than a constructed narrative.

The Neuroscience of Self-Deception

Recent advances in neuroscience have begun to illuminate the brain mechanisms underlying self-deception, revealing that it involves identifiable neural processes rather than being merely a metaphorical description of motivated reasoning.

Brain Regions Involved in Self-Deception

Neuroimaging studies suggest that self-deception involves interactions between brain regions associated with emotional processing, self-referential thinking, and cognitive control:

Key neural systems:

- Prefrontal cortex: Involved in reasoning, planning, and the construction of self-serving narratives

- Anterior cingulate cortex: Active when detecting conflicts between beliefs and evidence; may be suppressed during self-deception

- Amygdala: Emotional processing center that may flag threatening information for avoidance

- Default mode network: Associated with self-referential thinking and narrative construction

- Reward systems: May provide positive reinforcement for beliefs that protect self-image

Research suggests that self-deception isn't simply a failure to process information accurately—it's an active process where the brain works to maintain desired beliefs in the face of challenging evidence. Some studies show reduced activity in conflict-detection regions when people encounter information that contradicts their preferred self-image.

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

The Automaticity of Self-Deceptive Processes

Much self-deception appears to operate automatically, below the level of conscious awareness and control. The brain filters and interprets information in self-serving ways before conscious awareness even registers the information. This automaticity makes self-deception difficult to overcome through simple intention—by the time we consciously consider information, it's already been processed through self-protective filters.

Automatic self-deception processes:

- Selective attention that automatically gravitates toward confirming information

- Biased memory encoding that favors self-enhancing interpretations

- Automatic emotion regulation that dampens responses to threatening information

- Rapid categorization of information as credible or not credible based on consistency with existing beliefs

- Unconscious generation of rationalizations and justifications

Understanding the automaticity of self-deception has important implications for efforts to overcome it: simply deciding to be more honest with oneself is often insufficient because the relevant processes operate before and below conscious decision-making.

Self-Deception and Mental Health

The relationship between self-deception and mental health is complex—some forms of self-deception may actually support psychological well-being, while others contribute to mental health problems.

Positive Illusions and Psychological Health

Paradoxically, research has found that mentally healthy individuals often hold mildly positive illusions about themselves—they view themselves somewhat more positively than evidence warrants, believe they have more control than they actually do, and are mildly optimistic about their futures. These "positive illusions," identified by psychologist Shelley Taylor, appear to support mental health by maintaining motivation, self-esteem, and engagement with life.

Adaptive positive illusions include:

- Slightly inflated self-esteem that buffers against failure

- Mild illusion of control that supports active engagement

- Moderate optimism that maintains motivation

- Generous interpretation of ambiguous feedback

- Focus on strengths rather than weaknesses

Interestingly, people with depression often show more accurate self-assessment—a phenomenon called "depressive realism." This suggests that some degree of self-enhancing bias may be psychologically adaptive, with both too little and too much self-deception potentially problematic.

When Self-Deception Becomes Pathological

While mild self-enhancement may be adaptive, more severe or rigid self-deception can contribute to psychological problems and impede recovery:

Problematic self-deception patterns:

- Denial in addiction that prevents recognition of substance problems

- Minimization of symptoms that delays treatment-seeking

- Self-deception about relationship patterns that perpetuates dysfunction

- Avoidance of trauma processing through protective denial

- Rigid defense mechanisms that prevent psychological growth

- Narcissistic self-deception that damages relationships and prevents learning

In therapeutic contexts, gently addressing self-deception is often necessary for progress. However, this must be done carefully—aggressive confrontation of defenses can trigger retreat into deeper self-deception, while gradual, compassionate exploration can create conditions for greater honesty.

Overcoming Self-Deception: Strategies for Honest Self-Assessment

While self-deception is deeply ingrained in human psychology and serves genuine psychological functions, it is possible to become more aware of our tendencies to deceive ourselves and to make more honest, accurate assessments of ourselves and our situations. This doesn't mean eliminating all self-deception—which may be neither possible nor desirable—but rather developing greater capacity to recognize when self-deception is operating and choosing when to look more honestly.

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Practice Radical Honesty with Yourself

Radical honesty involves a commitment to confronting uncomfortable truths about yourself and your situation, even when doing so is painful. This practice requires both courage—the willingness to face what you'd rather avoid—and self-compassion, the ability to acknowledge unflattering truths without harsh self-judgment that would make honesty too threatening.

Radical honesty practices:

- Regularly ask yourself what you might be avoiding acknowledging

- Notice when you feel defensive and explore what the defensiveness protects

- Challenge your own rationalizations and justifications

- Acknowledge mistakes and failures without excessive excuse-making

- Face uncomfortable truths in small doses to build tolerance

- Distinguish between self-criticism and honest self-assessment

Seek External Feedback and Perspectives

Because self-deception operates largely outside conscious awareness, external perspectives can reveal blind spots that we cannot see ourselves. Trusted friends, family members, mentors, therapists, or coaches can provide feedback that circumvents our self-protective filters—if we create conditions that make honest feedback possible and can receive it non-defensively.

Feedback-seeking practices:

- Actively request honest feedback from trusted others

- Create safety for others to be honest by responding well to difficult feedback

- Seek feedback from multiple sources to identify patterns

- Ask specific questions rather than general ones

- Consider formal feedback mechanisms like 360-degree reviews

- Work with a therapist or coach who can provide objective perspective

Challenge Your Cognitive Biases Actively

Rather than passively accepting the biased information your mind naturally presents, actively challenge confirmation bias and other cognitive distortions by deliberately seeking out information that contradicts your preferred beliefs. This creates a more balanced information environment that makes self-deception harder to maintain.

Bias-challenging practices:

- Deliberately seek out information that challenges your beliefs

- Steelman opposing positions before dismissing them

- Ask "What would convince me I'm wrong about this?"

- Notice when you're scrutinizing some evidence more than other evidence

- Consider alternative explanations for evidence you find convincing

- Be suspicious of beliefs that happen to be convenient or comfortable

Engage in Regular Self-Reflection

Dedicated time for self-reflection—through journaling, meditation, therapy, or structured self-examination—creates space to explore thoughts, feelings, and patterns that daily busyness keeps from awareness. Regular reflection builds self-knowledge that makes self-deception easier to recognize.

Self-reflection practices:

- Keep a journal exploring thoughts, feelings, and patterns

- Practice meditation that develops awareness of mental processes

- Schedule regular time specifically for self-examination

- Use structured reflection questions to guide inquiry

- Review past decisions and their outcomes honestly

- Work with a therapist to explore deeper patterns

Embrace Uncertainty and Imperfection

Much self-deception arises from the desire for certainty, control, and positive self-image. Cultivating greater tolerance for uncertainty, acceptance of imperfection, and recognition that being wrong or flawed doesn't threaten core worth reduces the psychological pressure that drives self-deception.

Acceptance practices:

- Practice acknowledging "I don't know" without anxiety

- Recognize that being wrong is normal and often valuable

- Distinguish between making mistakes and being fundamentally flawed

- Accept that uncertainty is inherent in most decisions

- Value accuracy over feeling good about beliefs

- Recognize that imperfection is universal and doesn't diminish worth

Create Conditions That Support Honesty

Environmental and structural changes can support honest self-assessment by reducing the social and practical costs of acknowledging truth. When honesty is rewarded rather than punished, self-deception becomes less necessary.

Environmental supports for honesty:

- Build relationships where honest feedback is valued and safe

- Create accountability structures that encourage truthful reporting

- Design decision processes that invite challenge and dissent

- Reduce stakes of being wrong to make honesty less threatening

- Separate judgment of ideas from judgment of persons

- Celebrate correction and learning, not just being right

FAQ

Navigating the Mind Games of Self-Deception

Self-deception is a double-edged sword woven deeply into human psychology. On one edge, it can protect us from overwhelming psychological pain, enhance our social effectiveness, preserve our sense of self, and help us persist through difficulties. On the other edge, it undermines our decision-making, keeps us trapped in unfulfilling situations, damages our relationships, and disconnects us from our authentic selves.

By becoming more aware of our tendencies to deceive ourselves—recognizing the forms self-deception takes, understanding its psychological drivers, noticing its operation in our daily lives—we gain the capacity to choose when self-protective distortion serves us and when it harms us. We develop the ability to face uncomfortable truths when facing them would improve our lives, while maintaining compassion for the very human tendency to look away from what hurts.

The goal is not to eliminate self-deception entirely—it's woven too deeply into human cognition for that, and it serves genuine functions that complete elimination might harm. Rather, the goal is developing what we might call "honest self-awareness"—the capacity to recognize when we're engaging in mind games with ourselves and to choose, with courage and self-compassion, to face reality when doing so would serve our genuine well-being and growth.

In the end, the path beyond self-deception is not harsh self-criticism or relentless truth-telling regardless of cost. It's the gentler but no less courageous path of honest inquiry, of asking ourselves what we might be avoiding and whether facing it might serve us, of building the internal security that makes truth less threatening, and of recognizing that our worth doesn't depend on being perfect or always right.

Only through this compassionate honesty can we break free from the traps of self-deception and make decisions that truly align with our authentic values, genuine interests, and deepest aspirations for who we want to become.

This article provides general information about self-deception and psychological processes and is intended for educational purposes. If you're struggling with patterns of thought or behavior that significantly impact your well-being, relationships, or functioning, consider consulting with a licensed mental health professional who can provide personalized assessment and support.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.