The Neuroscience of Habit Loops: How to Rewire Your Brain for Success

The Neuroscience of Habit Loops: How to Rewire Your Brain for Success

Content

Content

Habits shape our lives in profound and far-reaching ways that most people never fully appreciate. From the moment we wake up until we go to bed, much of our behavior is governed by automatic routines that operate largely below the level of conscious awareness. These habits can be extraordinarily beneficial—like exercising regularly, eating nutritiously, saving money consistently, or maintaining productive work routines—or they can be profoundly detrimental, undermining our health, relationships, finances, and life goals through patterns like procrastination, emotional eating, excessive screen time, or substance abuse. But why are some habits so remarkably hard to break, even when we desperately want to change them? And why do other habits seem nearly impossible to form, despite our best intentions and repeated attempts?

The answer lies in the neuroscience of habit loops—a process deeply embedded in the architecture of our brains that drives our daily actions far more than most people realize. Understanding this neuroscience isn't merely an academic exercise; it's the key to unlocking your potential for lasting behavioral change. When you understand how habits are formed, maintained, and modified at the neurological level, you gain powerful leverage over your own behavior and can begin to consciously shape the automatic patterns that determine so much of your daily life and long-term outcomes.

In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the fascinating neuroscience of habit formation, examine how habit loops work at the level of brain structures and neural pathways, and offer practical, science-based strategies for rewiring your brain to build habits that propel you toward success. By understanding the science behind habits, you can take genuine control of your behavior, break free from self-destructive patterns that have held you back, and cultivate routines that support your most important long-term goals.

The Power of Habits

Habits are the foundation of our daily lives, operating as the invisible infrastructure that supports—or undermines—everything we do. They streamline our actions, dramatically reduce cognitive load, and enable us to navigate complex environments with minimal mental effort. Without habits, we would be exhausted by noon from the mental energy required to consciously deliberate every small decision and action. In fact, research suggests that up to 40-45% of our daily activities are driven by habits, not conscious decisions. This remarkable statistic means that our automatic routines, rather than our conscious intentions, often determine our success or failure in virtually every domain of life—health, relationships, career, finances, and personal development.

Why Habits Matter

The impact of habits on life outcomes cannot be overstated. Positive habits—established and maintained over time—can lead to dramatically improved physical and mental health, substantially greater productivity, long-term financial stability, and stronger, more satisfying relationships. They compound over time, with small daily actions accumulating into transformative life changes. Conversely, negative habits can systematically undermine our goals and create self-sabotaging cycles that trap us in patterns of failure and frustration, despite our sincere desire to change.

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit. The chains of habit are too light to be felt until they are too heavy to be broken—understanding this is the first step to freedom.

— Will Durant (Philosopher, summarizing Aristotle)

The cumulative power of habits manifests in multiple ways:

- Compound effects: Small daily habits compound over time into massive results—30 minutes of daily reading becomes hundreds of books over a decade; daily exercise transforms health over years

- Cognitive efficiency: Habits free mental resources for higher-level thinking, creativity, and problem-solving by automating routine decisions

- Identity formation: Our habits shape our self-concept and identity; we become what we repeatedly do

- Stress reduction: Established positive routines reduce decision fatigue and the anxiety of constant deliberation

- Goal achievement: Long-term goals are achieved not through occasional heroic efforts but through consistent daily habits

The key to unlocking your potential, therefore, lies in understanding how habits work at the neurological level and learning how to deliberately rewire your brain to establish routines that align with your deepest aspirations and values.

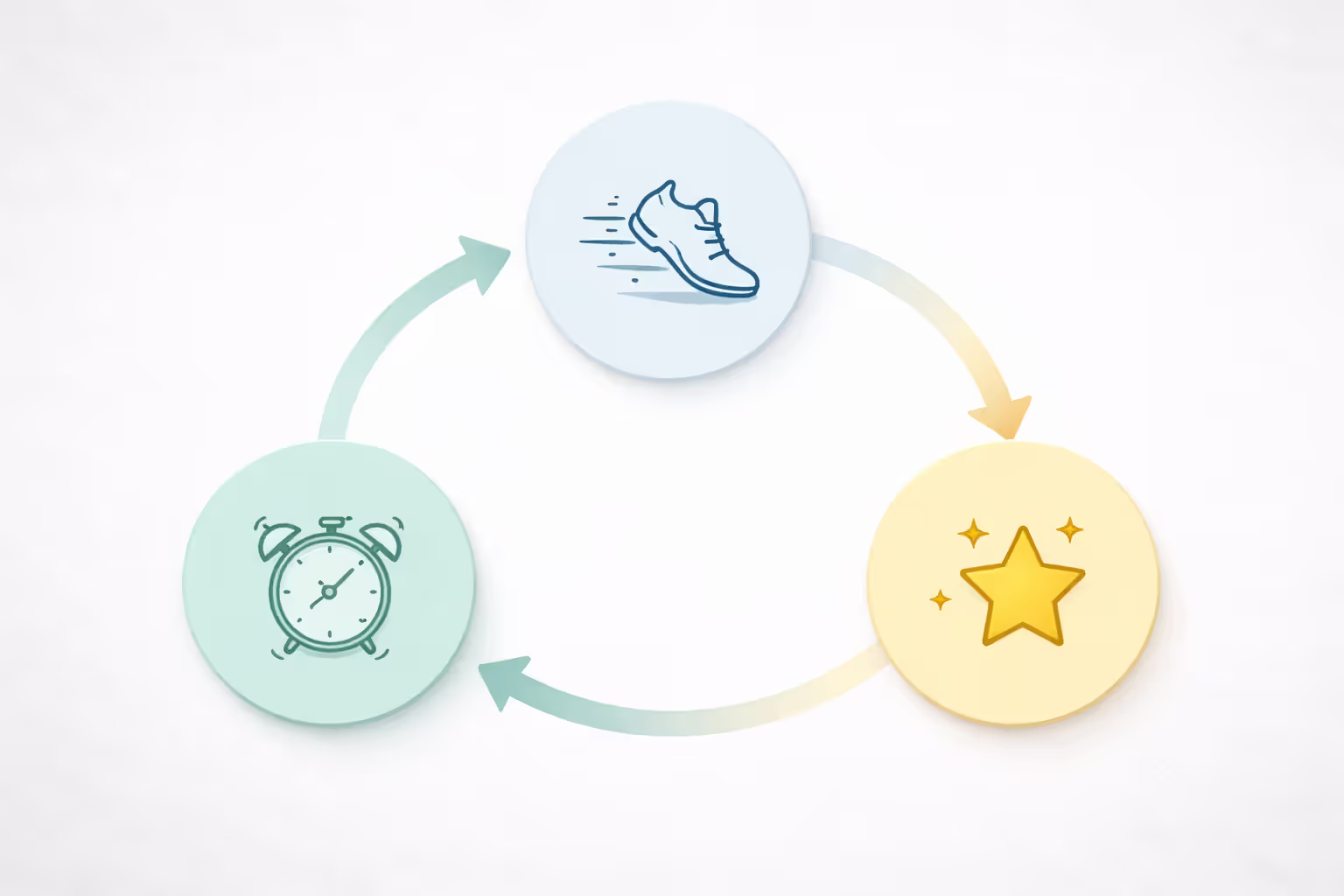

What is a Habit Loop? The Three Components of Habit Formation

To understand how habits work—and how to change them—we need to examine the basic structure of a habit loop. This concept was popularized by Charles Duhigg in his influential book The Power of Habit and has become a cornerstone framework for understanding habit formation in both scientific and popular contexts. The habit loop provides a clear model for analyzing existing habits and strategically building new ones.

The Three Components of a Habit Loop

Cue (Trigger): The cue is the trigger that initiates the habit sequence. It signals to the brain that it's time to enter automatic mode and which habit to deploy. Cues can be external stimuli—such as a specific time of day, a particular location, the presence of certain people, or environmental signals—or internal states like boredom, stress, fatigue, hunger, or specific emotions. Understanding your habit cues is the first step toward changing your habits.

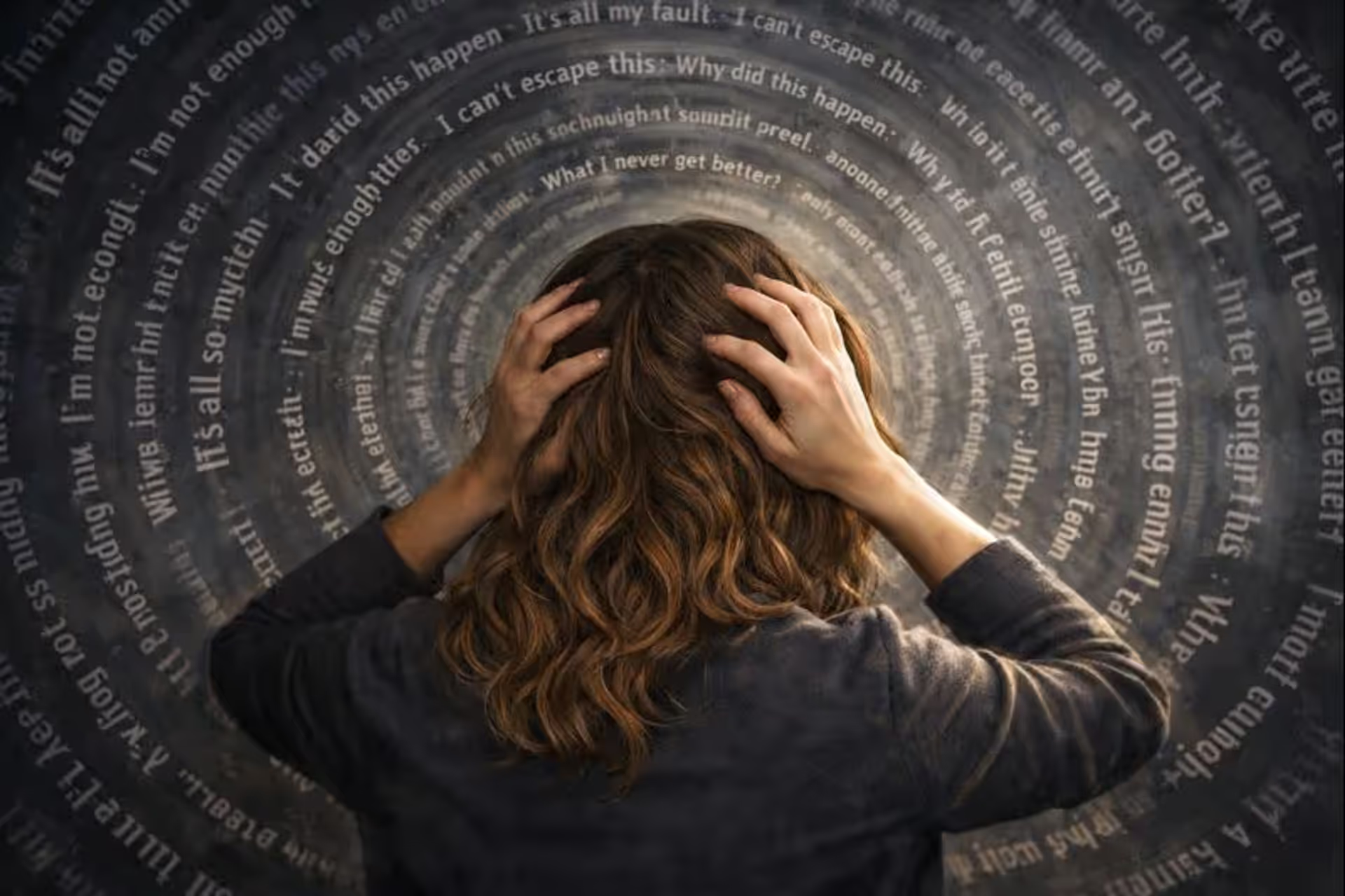

Routine (Behavior): The routine is the behavior or action you perform in response to the cue. This is the habit itself—the actual behavior pattern that unfolds automatically once triggered. Routines can be physical (brushing teeth, reaching for a snack), mental (worrying, ruminating), or emotional (reacting with anger, withdrawing). They can be simple single actions or complex sequences of behaviors.

Reward: The reward is the positive outcome that reinforces the habit loop and teaches the brain that this sequence is worth remembering and repeating. Rewards satisfy some craving and provide the brain with information about whether the routine is worth encoding. Rewards can be tangible (like the taste of food or a purchase) or intangible (like a sense of accomplishment, relief from boredom, social connection, or reduction of anxiety).

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

How the Habit Loop Reinforces Behavior

When a habit loop is repeated frequently, the brain learns to associate the cue with the routine and anticipate the reward. This association becomes progressively stronger with each repetition. Over time, the loop becomes increasingly automatic, and the behavioral pattern is gradually transferred from conscious control to storage in the brain's basal ganglia—a set of structures specialized for storing and executing automatic behavioral sequences.

The reinforcement process follows a predictable pattern:

- Initial learning: The behavior requires conscious attention, effort, and prefrontal cortex engagement

- Pattern recognition: The brain begins to recognize the cue-routine-reward sequence

- Chunking: The entire sequence becomes "chunked" into a single automatic unit

- Automation: Control shifts from prefrontal cortex to basal ganglia; behavior becomes effortless

- Craving development: The brain begins to anticipate and crave the reward upon encountering the cue

This process of automation is what makes habits so powerful—and, at times, so frustratingly difficult to change. Once a habit is fully formed, it can be triggered and executed with virtually no conscious thought or effort.

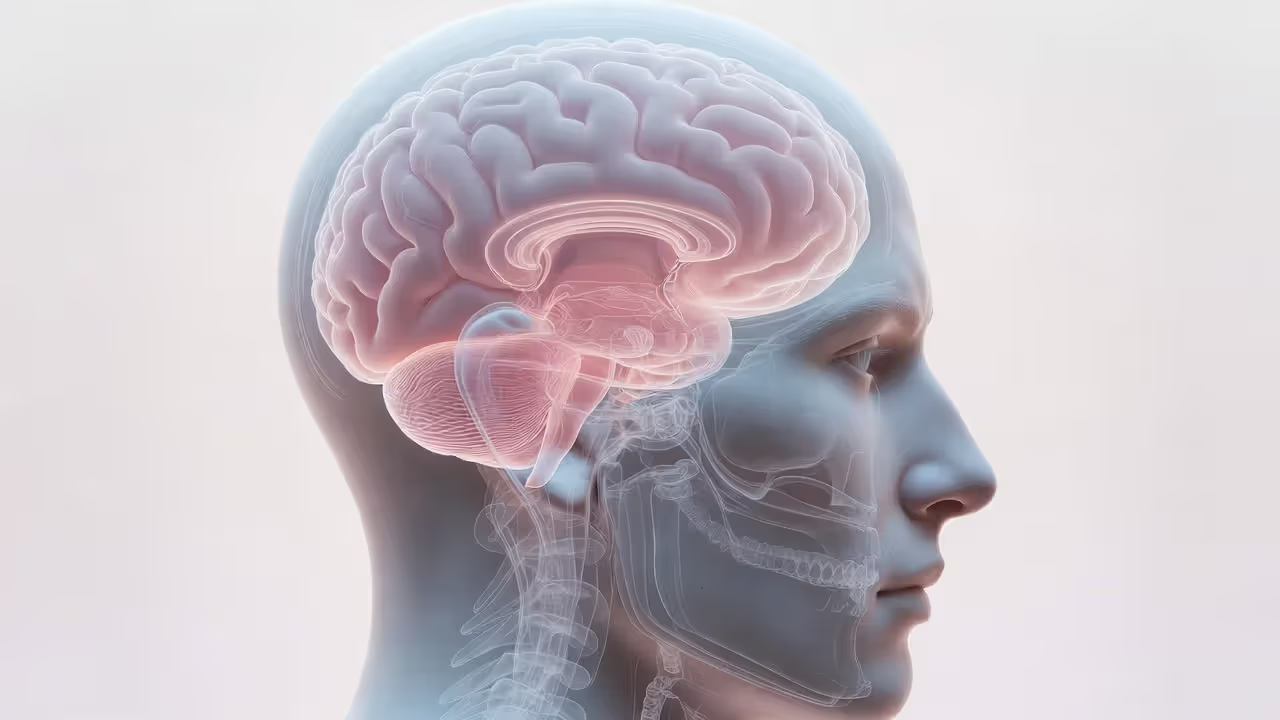

The Brain's Role in Habit Formation

The Power of Habits

Habit formation is deeply rooted in the brain's architecture, involving specific neural structures that have evolved to automate repeated behaviors. Understanding which parts of the brain are involved in habit formation—and how they interact—illuminates why habits are so hard to change and how we can leverage this knowledge to build better routines more effectively.

The Basal Ganglia: The Brain's Habit Center

The basal ganglia is a group of interconnected structures located deep within the brain that plays the central role in habit formation, storage, and execution. These structures—including the striatum, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra—are responsible for storing and executing patterns of behavior that have become habitual through repetition.

When you first learn a new skill or behavior, like driving a car, playing a musical instrument, or typing on a keyboard, the prefrontal cortex (responsible for conscious decision-making and deliberate control) is heavily involved. Learning requires attention, effort, and conscious processing. But as the behavior is repeated and becomes automatic, control gradually shifts to the basal ganglia, which takes over the process and allows the prefrontal cortex to disengage and focus on other tasks.

Key functions of the basal ganglia in habit formation:

- Pattern storage: Encoding and storing the neural representations of habitual behavioral sequences

- Sequence execution: Running stored behavioral programs automatically once triggered

- Efficiency optimization: Refining habits to become more efficient and require less cognitive resources

- Contextual triggering: Recognizing cues that signal when to deploy specific habits

- Chunking: Grouping sequences of actions into single automatic units

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Decision-Making Hub

The prefrontal cortex—located at the front of the brain behind the forehead—is the seat of executive function, involved in planning, decision-making, impulse control, and exerting willpower. When forming a new habit or attempting to break an old one, the prefrontal cortex must work hard to override the automatic routines stored in the basal ganglia and consciously direct behavior toward the desired action.

This is why changing habits feels so mentally exhausting, especially in the early stages—the prefrontal cortex is energy-intensive and has limited capacity for sustained effort. The good news is that this effort is temporary; once the new habit becomes sufficiently ingrained and transfers to the basal ganglia, the prefrontal cortex can relax, and the behavior becomes effortless.

The prefrontal cortex contributes to habit change through:

- Goal setting: Establishing the intention to form or break habits

- Inhibitory control: Suppressing automatic responses to allow new behaviors

- Monitoring: Tracking behavior and noticing when habits are triggered

- Decision-making: Choosing to engage in new routines rather than old ones

- Self-regulation: Managing the discomfort of changing established patterns

How the Basal Ganglia Drives Automatic Behavior

The basal ganglia's primary role in habit formation is to identify patterns in behavior and automate them to conserve precious cognitive resources. This automation is profoundly beneficial because it allows us to perform routine tasks—walking, driving, eating, speaking—without expending significant mental energy, freeing up the brain's limited conscious processing capacity for more complex, novel, or important tasks that require deliberate attention.

The Habit Automation Process

When a habit loop is first formed, the brain actively engages in each step of the process. You consciously notice the cue, deliberately choose and perform the routine, and explicitly register the reward. This initial phase requires attention and effort. However, as the habit is repeated consistently over time, the basal ganglia begins to recognize the pattern and starts "chunking" the behavior—grouping the cue, routine, and reward into a single, automatic sequence that can be triggered and executed as a unit.

Stages of habit automation:

- Conscious execution: Full attention required; behavior is effortful and prone to error

- Pattern recognition: Brain begins identifying the recurring sequence

- Partial automation: Some elements become automatic while others still require attention

- Chunking: Entire sequence becomes unified; executed as a single behavioral unit

- Full automation: Behavior runs on "autopilot" with minimal conscious involvement

Eventually, this sequence can be triggered with minimal conscious effort. When you encounter the cue, the entire behavioral routine unfolds automatically, almost like a program running in the background of a computer. This explains why you can drive to work while thinking about something entirely unrelated, or why you might find yourself eating an entire bag of chips without any conscious decision to do so.

Why the Basal Ganglia Resists Change

Once a habit is automated and stored in the basal ganglia, the brain becomes remarkably resistant to changing it. This resistance occurs because the brain views habits as valuable energy-saving mechanisms that should be preserved. From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to automate frequently repeated behaviors was crucial for survival—it freed up cognitive resources for detecting threats, solving novel problems, and responding to changing circumstances.

Overriding an established habit requires significant cognitive effort, which the brain interprets as inefficient and potentially threatening to its energy balance. The brain is fundamentally conservative in this regard—it prefers to maintain established patterns rather than expend resources creating new ones. This is why even when we consciously, desperately want to change a habit, it can be extraordinarily difficult to break free from the automatic behavior patterns stored in the basal ganglia.

Habits are the brain's way of saving energy and increasing efficiency. The problem is that the brain doesn't distinguish between good and bad habits—it will automate whatever you repeat, which is why conscious intention is so important.

— Dr. Wendy Wood (Psychologist, Author of "Good Habits, Bad Habits")

Neuroplasticity: How the Brain Adapts to Habit Change

The concept of neuroplasticity—the brain's remarkable ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life—is fundamental to understanding both habit formation and habit change. Every time you repeat a behavior, you strengthen the neural pathway associated with that action. The neurons that fire together during the habit literally wire together more strongly, making the behavior easier and more automatic to perform in the future.

Conversely, when you stop engaging in a behavior consistently, the neural connections that supported it gradually weaken through a process called synaptic pruning. The pathway doesn't disappear entirely—old habits can be reactivated—but it becomes less dominant and less easily triggered. Understanding neuroplasticity provides hope and practical guidance for anyone seeking to change their habits.

Creating New Neural Pathways

To build a new habit, you must create a new neural pathway by consistently pairing a cue with a new behavior and following it with a reward. Each time you complete this sequence, the connections between the neurons involved become slightly stronger. With enough repetition—research suggests anywhere from 18 to 254 days depending on the habit and person, with 66 days being average—the pathway becomes robust enough that the behavior becomes automatic.

Principles for building new neural pathways:

- Consistency over intensity: Regular, moderate repetition is more effective than occasional intense efforts

- Context stability: Performing the habit in the same context (time, place, preceding action) strengthens the cue-response connection

- Immediate reward: Connecting the behavior with immediate positive reinforcement accelerates pathway formation

- Emotional engagement: Habits connected with positive emotions form stronger neural connections

- Progressive building: Starting small and gradually increasing complexity helps pathways form successfully

Breaking Old Pathways

Breaking an established habit requires creating competing neural pathways that can override the old ones. Importantly, this means that instead of trying to simply erase or suppress an old habit—which is largely impossible—you need to replace it with a new routine that satisfies the same underlying craving or need. This approach, known as habit substitution, is far more effective than attempting to eliminate a habit through willpower alone.

The habit substitution process:

- Identify the craving: Understand what need or desire the old habit is satisfying

- Design an alternative: Create a new routine that addresses the same craving

- Maintain the cue: Keep the same trigger but redirect it to the new behavior

- Ensure reward: Make sure the new routine provides satisfying reward

- Repeat consistently: Strengthen the new pathway through repetition until it becomes dominant

The Science of Craving: Why Habits Are So Hard to Break

Cravings are the driving force behind habits—they are what transform a simple cue-routine-reward sequence into a powerful, self-perpetuating loop. Cravings are the brain's way of signaling that it expects and desires a reward, creating the motivational push that propels us into the habit routine. Understanding the neuroscience of cravings illuminates why habits are so persistent and how to harness the power of craving to form beneficial new habits.

How Cravings Activate the Brain's Reward System

Cravings are generated in the brain's reward system, a network of structures that evolved to motivate behaviors essential for survival—seeking food, water, shelter, social connection, and reproduction. This system includes the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and portions of the prefrontal cortex. When you experience a craving, these areas release dopamine, creating a powerful sense of anticipation, desire, and motivation to engage in the behavior that will deliver the expected reward.

The neurological sequence of craving:

- Cue detection: The brain recognizes a trigger associated with a habit

- Memory activation: Previous experiences of reward are recalled

- Dopamine release: Anticipatory dopamine creates the subjective experience of craving

- Motivation generation: The craving produces an urge to perform the routine

- Behavior execution: The habit routine is performed, often automatically

- Reward evaluation: The actual reward is compared to expectation, updating future cravings

The Anticipation vs. the Reward

Research has revealed a fascinating and counterintuitive finding about dopamine and habit: dopamine levels spike most dramatically during the anticipation of a reward, not during the reward itself. The craving—the wanting—is often neurologically more powerful than the actual pleasure derived from the habit. This is why you might crave a particular food intensely, eat it, and find the actual experience somewhat disappointing compared to the anticipation.

This anticipation-reward gap explains several puzzling aspects of habits:

- Why we continue habits even when they no longer satisfy us

- Why the pleasure of habits often diminishes over time while the craving remains strong

- Why breaking habits feels so difficult despite knowing the reward isn't that great

- Why we often feel restless or dissatisfied even shortly after completing a habit

Understanding this dynamic can help you recognize that the powerful craving you feel before engaging in a bad habit is likely stronger than the actual satisfaction you'll receive, making it somewhat easier to resist.

Using Cravings to Build New Habits

You can leverage the power of cravings to build positive new habits by deliberately associating the new routine with a desirable, immediate reward. The key is creating positive anticipation around the new habit so that your brain begins to crave performing it. This requires identifying rewards that genuinely satisfy you and consistently pairing them with the new behavior.

Strategies for building craving for new habits:

- Immediate rewards: Pair the new habit with something immediately pleasurable

- Visualization: Vividly imagine the rewards of the habit to build anticipation

- Progress tracking: Use visible progress markers that create anticipation for continuation

- Social rewards: Involve others to add social approval as an additional reward

- Identity reinforcement: Frame the habit as evidence of who you're becoming

How the Brain Builds and Reinforces Habits

The brain reinforces habits through a neurological process called long-term potentiation (LTP), which strengthens the synaptic connections between neurons. Each time a habit is performed, the neurons involved fire together, and this simultaneous activation strengthens the connections between them according to Hebb's principle: "neurons that fire together wire together."

The Role of Repetition in Habit Formation

Repetition is the fundamental key to building and maintaining habits. There is simply no substitute for consistent practice when it comes to habit formation. Each time a habit is performed, the brain releases neurotransmitters that strengthen the synaptic connections between the neurons involved in the habit loop. With enough repetition, these connections become so strong that the habit becomes automatic—the default behavior that the brain executes with minimal conscious involvement.

How repetition strengthens habits:

- Synaptic strengthening: Each repetition physically strengthens neural connections

- Myelination: Repeated activation leads to increased myelin coating on neural pathways, speeding signal transmission

- Pathway efficiency: The neural route becomes faster and more efficient with use

- Automaticity development: Conscious effort required decreases with each repetition

- Cue sensitivity: The brain becomes increasingly sensitive to habit triggers

The Impact of Consistency on Habit Strength

Consistency is crucial for habit formation because it reduces variability in the habit loop, making it easier for the brain to recognize patterns and automate the behavior. When a habit is performed inconsistently—at different times, in different contexts, with varying routines—the brain has a harder time "chunking" the behavior into an automatic sequence. The pattern is less clear, the associations are weaker, and automation is delayed or prevented.

This is why it's essential to establish consistent cues, maintain consistent routines, and provide consistent rewards when building a new habit. The more stable and predictable the habit loop, the faster it will become automatic.

Breaking Bad Habits: The Neuroscience of Habit Disruption

Breaking a bad habit is not simply a matter of willpower, motivation, or wanting to change badly enough. It involves disrupting the neural pathways that have been strengthened through repetition and creating new, competing pathways that can eventually override the old ones. Understanding the neuroscience of habit disruption provides practical strategies for eliminating unwanted habits and replacing them with positive alternatives.

The Habit Disruption Process

Identify the Cue: The first and most important step in breaking a habit is to identify the specific cue or cues that trigger the behavior. This requires careful observation and often journaling or tracking. Cues can be temporal (time of day), environmental (location, visual signals), emotional (stress, boredom, anxiety), social (presence of certain people), or related to preceding actions.

Understand the Craving: What reward is the habit actually providing? What need or desire is being satisfied? Often the true reward is not obvious. Someone who habitually eats cookies in the afternoon might actually be craving social interaction, a break from work, or relief from stress—not the cookies themselves.

Replace the Routine: Instead of trying to suppress or eliminate the habit through willpower alone, replace it with a new routine that satisfies the same craving but aligns with your goals. If the afternoon cookie habit is really about taking a break, a short walk might satisfy the same need. If it's about stress relief, deep breathing might work.

Change the Environment: Modify your environment to remove or reduce exposure to cues and to make the old habit harder to perform while making alternative behaviors easier. Environmental design is often more effective than willpower.

Be Patient and Persistent: Neural pathways don't change overnight. Breaking a well-established habit and building a new one takes time, repetition, and tolerance for the discomfort of resisting ingrained patterns.

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Using Inhibitory Control to Break Habits

Inhibitory control is the brain's ability to suppress automatic responses, allowing us to stop ourselves from acting on impulse. The prefrontal cortex is heavily involved in inhibitory control, and strengthening this capacity can help you resist the urge to engage in unwanted habits. Fortunately, inhibitory control can be strengthened through practice, much like a muscle.

Methods for strengthening inhibitory control:

- Mindfulness meditation: Regular practice improves prefrontal cortex function and self-regulation

- Cognitive-behavioral techniques: Learning to identify and challenge automatic thoughts

- Self-monitoring: Tracking behavior increases awareness and provides opportunity for intervention

- Implementation intentions: Pre-planning responses to triggers reduces need for in-the-moment willpower

- Regular exercise: Physical activity improves executive function and inhibitory control

- Adequate sleep: Sleep deprivation impairs prefrontal cortex function and self-control

How to Rewire Your Brain for Success

Brain for Success

Rewiring your brain for success involves deliberately creating new habit loops that support your long-term goals while weakening or replacing loops that undermine them. This process requires consistency, patience, strategic thinking, and a deep understanding of how habits are formed and maintained at the neurological level.

The Four-Step Process for Building New Habits

Set a Clear Intention: Define exactly what habit you want to build, why it matters to you, and what it will look like in practice. A vague intention like "exercise more" is far less effective than a specific plan like "go for a 20-minute run every weekday morning at 7 a.m. before breakfast." The more specific and vivid your intention, the more likely it is to translate into actual behavior.

Create a Reliable Cue: Choose a consistent, unavoidable cue that will trigger the new habit. The best cues are specific, consistent, and already embedded in your routine. Using an existing habit as a cue (habit stacking) is particularly effective—"After I pour my morning coffee, I will write in my journal for 5 minutes."

Perform the Routine: Start with a version of the habit that is small and easy enough that you can do it even on your worst days. Consistency trumps intensity in habit formation. Beginning with "do one push-up" is more effective than "do 50 push-ups" because it removes barriers to starting and ensures the streak is maintained.

Reward Yourself: Choose a reward that is immediate, genuine, and satisfying. The reward should be meaningful to you personally and should occur immediately after the routine. This could be a tangible reward, a moment of self-acknowledgment, or simply the intrinsic satisfaction of the activity itself.

The most effective way to change your habits is to focus not on what you want to achieve, but on who you wish to become. Your habits shape your identity, and your identity shapes your habits. This reciprocal relationship is the key to lasting change.

— James Clear (Author of "Atomic Habits")

Using Positive Reinforcement Effectively

Positive reinforcement involves rewarding yourself for performing the desired habit, which strengthens the neural pathways associated with that behavior and increases the likelihood of repetition. For positive reinforcement to be maximally effective, the reward should be immediate (not delayed), certain (reliably delivered), and genuinely pleasurable (actually satisfying to you).

Principles of effective reinforcement:

- Immediacy: The closer the reward is to the behavior, the stronger the association

- Consistency: Reward the behavior every time, especially when establishing the habit

- Appropriateness: Match the reward size to the effort required

- Personal relevance: Choose rewards that genuinely matter to you

- Non-undermining: Ensure the reward doesn't undermine the goal of the habit

The Role of Dopamine in Habit Formation

Dopamine is the neurotransmitter most closely associated with habit formation. Often mischaracterized as the "pleasure chemical," dopamine's primary role is actually in motivation, anticipation, and learning rather than pleasure itself. It drives the wanting, craving, and goal-directed behavior that underlies habits. Understanding how dopamine works provides powerful leverage for building positive habits and breaking negative ones.

Dopamine and the Anticipation of Reward

As discussed earlier, dopamine levels spike most dramatically in anticipation of a reward, not during the reward itself. This anticipatory dopamine creates the motivational push that propels behavior. When a cue associated with a habit is encountered, dopamine is released in anticipation of the reward, creating the craving that drives the routine.

This means that creating a sense of anticipation is a powerful tool for habit formation. By visualizing the positive outcomes of your habit, setting small milestones that create excitement, or building anticipation through countdown mechanisms, you can increase dopamine levels and enhance motivation to perform the habit.

How to Leverage Dopamine for Habit Formation

Set Clear, Achievable Goals: Define specific, achievable goals that create a sense of anticipation. Breaking large goals into smaller milestones provides more frequent dopamine hits and maintains motivation.

Celebrate Small Wins: Each time you complete the habit, acknowledge your success, even briefly. This releases dopamine and reinforces the behavior. The celebration doesn't need to be elaborate—a moment of self-recognition or a small treat can be effective.

Visualize the Outcome: Spend time vividly visualizing the positive outcomes of your habit. Mental simulation activates similar neural pathways to actual experience and can increase anticipatory dopamine.

Track Progress Visibly: Use a habit tracker, calendar, or other visual system to track your progress. Seeing the streak grow creates anticipation of continued success and reluctance to break the chain.

Create Accountability: Share your goals with others or use accountability partners. Social expectations create additional dopamine-mediated motivation.

The Habit Stacking Method: Building Success on Existing Routines

Habit stacking is a powerful technique that involves linking a new habit to an existing, well-established one. By using an established habit as the cue for a new behavior, you leverage the automaticity and reliability of the old habit to anchor and trigger the new one. This approach significantly reduces the cognitive effort required to remember and initiate the new habit.

How Habit Stacking Works

The formula for habit stacking is simple: "After I

, I will ." Choose a habit you already perform consistently and reliably—such as brushing your teeth, making coffee, sitting down at your desk, or eating lunch—and use it as the trigger for your new habit.Examples of habit stacks:

- "After I pour my morning coffee, I will meditate for two minutes."

- "After I sit down at my desk, I will write my three most important tasks for the day."

- "After I finish dinner, I will read for 15 minutes."

- "After I brush my teeth at night, I will review what I'm grateful for."

- "After I put on my workout clothes, I will do 10 squats."

Why Habit Stacking is Effective

Habit stacking works because it eliminates one of the biggest barriers to new habit formation: remembering to do the new behavior. By linking the new habit to an established routine, you create a clear, specific cue that reliably occurs. You also leverage the momentum and automaticity of the existing habit, making it easier to flow into the new behavior.

Additionally, habit stacking takes advantage of the brain's associative learning. The neural networks activated by the existing habit become linked to the new behavior, accelerating the formation of the new habit loop.

Using Visualization and Mental Rehearsal to Strengthen Habits

Visualization and mental rehearsal are powerful, often underutilized tools for habit formation. By vividly imagining yourself performing the habit, you activate many of the same neural pathways that would be involved in actually doing the behavior. This mental practice strengthens the relevant neural connections and makes the habit easier to execute in real life.

The Science of Visualization

Neuroscience research has demonstrated that mental rehearsal produces measurable changes in the brain similar to physical practice. Brain imaging studies show that imagining an action activates many of the same motor and cognitive regions as actually performing the action. Athletes, musicians, and other performers have long used visualization to enhance their skills, and the same principles apply to habit formation.

Benefits of visualization for habit formation:

- Neural pathway strengthening: Mental rehearsal strengthens the same connections as physical practice

- Increased self-efficacy: Visualizing success builds confidence in your ability to perform the habit

- Problem anticipation: Mental rehearsal allows you to anticipate and plan for obstacles

- Motivation enhancement: Imagining positive outcomes increases anticipatory dopamine and motivation

- Reduced anxiety: Familiarity with the behavior, even if only imagined, reduces anxiety about performing it

How to Use Visualization for Habit Formation

Practice vividly and specifically: Close your eyes and imagine yourself performing the habit in rich detail. Include as many sensory elements as possible—what you see, hear, feel, and even smell. The more vivid and specific the visualization, the more effective it is.

Visualize the entire sequence: Don't just imagine the habit itself; visualize the cue that triggers it, the environment you're in, the routine you perform, and the reward you experience afterward. This complete mental rehearsal strengthens the entire habit loop.

Include emotional content: Visualize how you will feel while performing the habit and after completing it. Emotional engagement strengthens memory formation and increases the power of visualization.

Practice regularly: Like physical practice, visualization is most effective when done regularly. Brief daily visualization sessions are more effective than occasional longer sessions.

Harnessing Willpower and Motivation: The Role of the Prefrontal Cortex

Motivation

Willpower and motivation are essential for habit formation, particularly in the early stages before the habit becomes automatic. The prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for executive function, self-control, planning, and decision-making, plays the central role in exerting willpower to establish new habits and resist the pull of old ones.

How to Strengthen and Conserve Willpower

Start Small: Begin with habits that are small and easy enough to perform even when willpower is depleted. Building habits gradually allows you to succeed consistently while conserving willpower for other demands.

Practice Mindfulness: Regular mindfulness meditation has been shown to increase prefrontal cortex activity and gray matter density, directly strengthening the brain regions involved in self-control. Even brief daily practice produces measurable benefits.

Limit Decision Fatigue: Willpower is a limited resource that can be depleted by making decisions. Reduce the number of decisions you make daily—through routines, simplification, and environmental design—to conserve willpower for important habit-related choices.

Protect Physical Resources: Willpower depends on physical resources, particularly glucose and rest. Ensure adequate sleep, nutrition, and stress management to maintain the physiological foundation of self-control.

Build Gradually: Willpower capacity can be increased through practice, much like building a muscle. Successfully exercising self-control in small matters gradually increases your capacity for larger challenges.

The Power of Environment in Shaping Habits

The environment has a profound, often underappreciated impact on habit formation and behavior. Our surroundings provide the cues that trigger habits and determine the level of friction involved in performing different behaviors. By strategically designing your environment, you can reduce reliance on willpower, make positive habits easier, and make negative habits harder—all without requiring constant conscious effort.

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

How to Shape Your Environment for Success

Eliminate Triggers for Unwanted Habits: Remove or minimize exposure to cues that trigger behaviors you want to avoid. If you're trying to reduce phone use, keep the phone in another room. If you're trying to eat healthier, don't keep junk food in the house. Out of sight often means out of mind.

Create Visual Cues for Desired Habits: Place reminders and cues for positive habits in prominent positions in your environment. Want to read more? Put a book on your pillow. Want to exercise? Lay out your workout clothes the night before. Want to drink more water? Keep a water bottle visible on your desk.

Reduce Friction for Positive Habits: Make the behaviors you want to perform as easy as possible. Remove obstacles, prepare in advance, and create a clear path to action. The less friction involved, the more likely the habit will be performed.

Increase Friction for Negative Habits: Conversely, make unwanted behaviors harder to perform. Add obstacles, create delays, and introduce inconvenience. Even small amounts of friction can significantly reduce the frequency of a behavior.

Design for Default Success: Arrange your environment so that the path of least resistance leads to your desired behaviors. When positive habits are the default option, they require no willpower to maintain.

FAQ

Building a Brain for Success

The neuroscience of habit loops reveals that habits are not merely behaviors we choose to perform—they are deeply ingrained neural patterns that physically shape our brains and fundamentally determine who we are and what we achieve. The grooves of habit, once formed, channel our behavior automatically, for better or worse. Understanding this science transforms our approach to personal change from willpower-based struggle to strategic neural rewiring.

By understanding the components of habit loops, the roles of the basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex, the power of neuroplasticity, and the mechanisms of craving and reward, you gain practical leverage over behaviors that once seemed impossibly difficult to change. You can work with your brain's natural learning mechanisms rather than fighting against them.

The strategies explored in this article—habit stacking, visualization, environmental design, the four-step habit formation process, dopamine leveraging, and habit substitution—provide a comprehensive toolkit for rewiring your brain for success. But knowledge alone is not enough. These strategies must be applied consistently, patiently, and with self-compassion when setbacks occur.

Ultimately, mastering your habits is about taking conscious control of your brain's wiring. It is about choosing deliberately what neural pathways to strengthen through repetition, what behaviors to automate, and what patterns to establish as the foundation of your daily life. With patience, persistence, understanding, and the right strategies, you can transform your life one habit loop at a time—building the neural infrastructure that supports the person you want to become and the life you want to live.

This article provides general information about the neuroscience of habit formation and is intended for educational purposes. While the strategies described are based on scientific research, individual results may vary. For persistent behavioral difficulties or mental health concerns, please consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.