Brain stuck on negative thoughts

Why Your Brain Amplifies Negative Thoughts

Ever wondered why negative thoughts seem to stick in your mind longer than positive ones, replaying endlessly like a broken record while pleasant memories fade quickly into the background? Why, after receiving both praise and criticism in the same performance review, your brain fixates obsessively on the negative feedback, turning it over and over while barely registering the compliments? Why a single critical comment from a colleague can overshadow dozens of supportive interactions, or why one awkward moment at a social gathering becomes the dominant memory of an otherwise enjoyable evening? This phenomenon is not unique to you, nor is it a sign of personal weakness, pessimism, or character flaw—it is a universal human experience driven by the brain's natural mechanisms that evolved over millions of years to keep our ancestors alive in a dangerous world.

Understanding why your brain amplifies negative thoughts is crucial for maintaining mental well-being, improving relationships, navigating life's challenges more effectively, and ultimately living a more balanced and fulfilling life. Without this understanding, we remain at the mercy of automatic mental processes that systematically distort our perception of reality, making the world seem more threatening and ourselves more inadequate than objective circumstances warrant. With this understanding, we gain the power to recognize these patterns when they occur, question their accuracy, and gradually retrain our brains toward a more balanced perspective that serves our modern lives rather than the survival imperatives of our prehistoric ancestors.

In this comprehensive article, we will delve deep into the psychological and neurological reasons behind this pervasive bias toward negativity, examining the evolutionary origins that shaped our brains, the neural structures that implement this ancient programming, and the cognitive patterns that amplify negativity far beyond what facts would justify. We will explore the profound impacts of negative thinking on your relationships, mental health, physical well-being, and daily life functioning. And most importantly, we will provide actionable, evidence-based strategies to break free from negativity's grip and cultivate a healthier, more balanced mental landscape that allows you to thrive rather than merely survive.

The Brain's Built-In Bias Toward Negativity

The brain is fundamentally wired for survival, not for happiness, contentment, or accurate perception of reality. This crucial distinction helps explain why we struggle so much with negative thoughts: our brains evolved not to make us feel good but to keep us alive long enough to reproduce and raise offspring. Long ago, when our ancestors lived in environments filled with immediate, life-threatening dangers—predators lurking in the tall grass, hostile neighboring tribes competing for scarce resources, unpredictable weather patterns that could mean starvation—it was absolutely vital for survival to pay close attention to negative experiences and potential threats. The cost-benefit analysis was starkly asymmetric: missing a danger cue could be immediately fatal, eliminating all future opportunities forever, while ignoring a positive event was merely a missed opportunity with no existential consequences.

This evolutionary programming became deeply embedded in our neural architecture over millions of years of natural selection, which consistently favored individuals whose brains were vigilant threat-detectors over those who focused on life's pleasures. Our ancestors who noticed the rustling in the bushes and assumed predator rather than wind survived to pass on their genes; those who were more relaxed about potential threats did not. The result is that we carry this ancient survival software in our modern skulls, even though we now live in environments incomparably safer than those our ancestors navigated. The mismatch between our evolved psychology and our modern circumstances creates much of our psychological suffering.

The brain is like Velcro for negative experiences but Teflon for positive ones. Negative experiences stick immediately and permanently, while positive experiences need to be held in awareness for 10-20 seconds to transfer from short-term to long-term memory.

— Dr. Rick Hanson

We react to email criticisms, social media slights, and professional setbacks with the same neurochemical cascade our ancestors experienced when facing a saber-toothed tiger, even though the objective threat levels are incomparably different. This negativity bias manifests in countless ways throughout daily life: we remember insults more vividly than compliments; we dwell on failures while quickly forgetting successes; we notice what is wrong in a situation before we notice what is right; we give more weight to negative information when forming impressions of others; and we feel the pain of losses more intensely than the pleasure of equivalent gains. All of these tendencies made excellent sense in the environment of evolutionary adaptation but create significant problems in modern life, where most of the "threats" we face are psychological rather than physical and where chronic stress activation damages rather than protects our health.

The Negativity Bias: Why the Brain is Hyper-Focused on the Negative

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

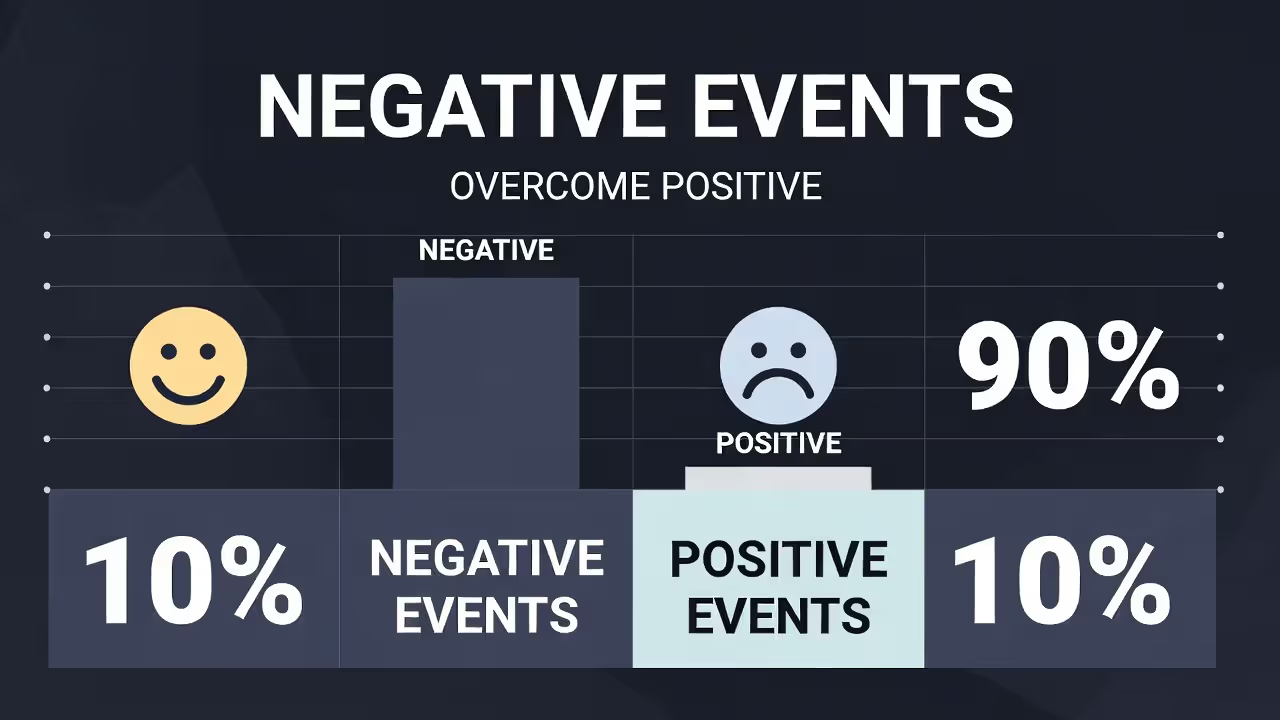

The negativity bias is the brain's systematic tendency to give more attention, more weight, and more durable memory encoding to negative experiences than to positive or neutral ones of equivalent intensity. This is not merely a tendency or preference but a fundamental feature of how human cognition operates, observable in infants, consistent across cultures, and measurable through sophisticated brain imaging studies. Research consistently demonstrates that negative information has a greater impact on our emotional and psychological states than positive information of comparable magnitude—one negative event, thought, or memory can overshadow multiple positive ones, creating a systematically skewed perception of reality that does not accurately reflect objective circumstances.

The asymmetry is striking in its consistency and magnitude across different domains of life. Studies suggest that it takes approximately five positive interactions to counterbalance a single negative interaction in close relationships—a ratio that has profound implications for how we must deliberately cultivate positivity to achieve emotional balance. Negative first impressions are significantly more resistant to change than positive ones, making it substantially harder to overcome a bad start than to squander a good one. Bad news travels faster and further than good news, shapes public opinion more powerfully, and is remembered longer and more vividly. Negative emotions like fear, anger, and disgust are processed faster and trigger stronger physiological responses than positive emotions like joy, gratitude, and contentment.

Why does this pervasive bias exist at a neural level?

The answer lies in the brain's structure, chemistry, and evolutionary history working together as an integrated system. The amygdala, an almond-shaped region deep in the brain's temporal lobe that serves as the primary center for processing emotions and detecting threats, is significantly more responsive to negative stimuli than to positive ones. When you encounter something potentially threatening or harmful—whether it is a physical danger like a car swerving toward you, a social threat like a contemptuous facial expression, or an abstract threat like criticism of your work—the amygdala rapidly processes this information and sends signals throughout the body, triggering the cascade of physiological changes known as the "fight or flight" response.

This amygdala-driven response involves the release of stress hormones including cortisol and adrenaline, increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, muscle tension, redirected blood flow to major muscle groups, and heightened sensory awareness—all preparing the body for emergency action against a threat. This reaction evolved to help early humans survive genuine physical threats, enabling rapid responses that could mean the difference between life and death. But in the modern world, this same system causes us to overreact to perceived threats that are not actually life-threatening: social rejection triggers the same stress response as physical danger; professional criticism activates the same neurochemical cascade as a predator encounter; financial uncertainty provokes the same fight-or-flight reaction as immediate physical peril. The physiological response is essentially the same whether we are facing a genuine threat to survival or a disappointing email, even though only one of these situations actually threatens our existence.

Neurological Studies on Negativity Bias

The scientific evidence for negativity bias is robust, replicated, and comes from multiple independent research methodologies. In a landmark study conducted by psychologist John Cacioppo at the University of Chicago, participants were shown pictures designed to evoke positive emotions (such as images of happy couples, beautiful scenery, or delicious food), negative emotions (such as mutilated bodies, aggressive animals, or scenes of violence), and neutral emotions (such as common household objects or neutral faces). Brain activity was measured using electroencephalography (EEG), which tracks electrical activity across the scalp with millisecond precision. The results were unambiguous and striking: negative images produced a significantly stronger response in the cerebral cortex than positive or neutral images, as measured by a brain wave component called the late positive potential (LPP), which reflects the allocation of attention and cognitive resources.

This stronger neural reaction to negative stimuli has been replicated across numerous studies using various methodologies, including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which provides detailed three-dimensional pictures of brain activity. These studies consistently show greater amygdala activation in response to negative stimuli, more extensive memory encoding for negative events, more elaborate cognitive processing of negative information, and longer-lasting emotional responses to negative compared to positive experiences. This enhanced neural processing of negative information explains several phenomena that we observe in everyday life: why negative experiences linger in our minds longer than positive ones; why we can remember specific insults from decades ago while struggling to recall compliments from last week; why a single negative review feels more significant than multiple positive ones; and why negative events tend to have such lasting impacts on how we feel, think, and behave—often far beyond what their objective significance would warrant.

The Role of Cognitive Distortions in Amplifying Negative Thoughts

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Beyond the brain's hardwired negativity bias, another powerful reason your mind amplifies negative thoughts lies in cognitive distortions—systematic errors in thinking that distort perception of reality in predictably negative directions. These irrational or exaggerated patterns of thinking act as mental magnifying glasses for negativity, taking ordinary disappointments and transforming them into catastrophes, converting single failures into evidence of permanent inadequacy, and filtering out positive information while spotlighting every negative detail. Cognitive distortions are not simply "negative thinking" in a general sense but specific, identifiable patterns that can be recognized, named, and corrected once we understand how they operate.

These mental traps develop through learning and life experience, often beginning in childhood and becoming increasingly automatic over time until they operate entirely outside conscious awareness. A child repeatedly criticized by a perfectionist parent may develop all-or-nothing thinking as an adult, experiencing anything less than perfect performance as total failure. Someone who experienced unpredictable loss may develop catastrophizing tendencies, always expecting the worst as a form of psychological preparation against future disappointment. These patterns become habitual over years of repetition, running automatically in the background of our minds like software programs we never consciously chose to install but that nonetheless shape our experience of reality.

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom. Cognitive distortions collapse this space, making negative reactions feel automatic and inevitable.

— Dr. Viktor Frankl

Common cognitive distortions that amplify negativity include:

Catastrophizing: This distortion involves imagining the worst possible outcome of a situation, even when such an outcome is extremely unlikely or even virtually impossible. A minor mistake at work becomes certainty of being fired and never finding employment again; a partner's irritability becomes evidence of imminent relationship collapse and lifelong loneliness; a headache becomes a suspected brain tumor requiring immediate medical attention. Catastrophizing hijacks the imagination, using it to create vivid mental movies of disaster that trigger the same stress response as actual threats. The brain cannot easily distinguish between vividly imagined catastrophe and reality, so catastrophizing creates genuine suffering over events that will never occur.

Overgeneralization: This pattern involves making broad, sweeping conclusions based on a single event or very limited evidence. One failed relationship becomes "I'm fundamentally unlovable and will never find a partner"; one rejected job application becomes "I'm unemployable and will never find work in my field"; one awkward social interaction becomes "I'm terrible with people and should avoid social situations." The linguistic markers of overgeneralization include words like "always," "never," "everyone," and "no one"—words that turn isolated incidents into universal laws that constrain our self-image and limit our behavior going forward.

Black-and-White Thinking: Also called all-or-nothing thinking or dichotomous thinking, this distortion involves viewing situations, people, and oneself in extreme terms without acknowledging any middle ground where most of reality actually resides. Performance is either perfect or completely worthless; people are either entirely trustworthy or total betrayers not deserving any confidence; outcomes are either complete success worthy of celebration or utter failure requiring shame. This thinking pattern eliminates the nuanced, realistic assessments that would allow for satisfaction with partial success, recognition of mixed outcomes, or acceptance of human imperfection in ourselves and others.

Emotional Reasoning: This distortion involves believing that if you feel a certain way, your feelings must accurately reflect external reality. "I feel anxious, so something bad must genuinely be about to happen"; "I feel inadequate, so I must actually be inadequate"; "I feel unloved, so I must not be worthy of love." Emotional reasoning treats subjective emotional states as reliable evidence about external circumstances, ignoring that emotions are influenced by countless factors—including the negativity bias itself, sleep quality, blood sugar levels, and random neurochemical fluctuations—that may have nothing to do with actual external situations.

Mental Filtering: This pattern involves focusing exclusively on negative details while filtering out positive information entirely, as if wearing special glasses that only allow negative light to reach our awareness. After a presentation that received mostly positive feedback with one critical comment, mental filtering causes obsessive focus on the single criticism while the praise goes unnoticed or is actively dismissed as insincere. This creates a systematically distorted picture of reality that reinforces negative self-perception and pessimistic worldviews, regardless of what is actually happening.

Personalization: This distortion involves taking excessive personal responsibility for events beyond one's control or interpreting others' behavior as specifically directed at oneself without supporting evidence. A friend's bad mood is interpreted as anger specifically at you rather than stress from their own life; a project's failure becomes entirely your fault despite team involvement and external factors; random negative events are seen as punishment or reflection of personal unworthiness.

These distortions create a self-reinforcing feedback loop where negative thoughts trigger negative emotions, which then provide apparent confirmation for the cognitive distortions through emotional reasoning, which generates more negative thoughts and more negative emotions in an escalating spiral. Over time, this cycle becomes a habitual way of processing information, creating deeply worn neural pathways that automatically channel experience through negative interpretive frameworks. Breaking these patterns requires first recognizing them when they occur, then deliberately and repeatedly practicing alternative interpretations until new neural pathways develop sufficient strength to compete with the established negative patterns.

The Psychological Impact of Rumination: Stuck in a Loop of Negative Thinking

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Have you ever found yourself replaying a mistake, embarrassment, or painful interaction over and over in your mind, unable to stop even though the repetition brings no relief and considerable distress? This mental process is known as rumination, and it represents one of the most damaging ways the brain amplifies negative thoughts and maintains negative emotional states long after the triggering event has passed. Rumination occurs when you repeatedly focus on distressing events, feelings, or problems, turning them over and over in your mind without making progress toward resolution, acceptance, or constructive action. Unlike productive problem-solving or healthy emotional processing, rumination is circular, repetitive, and ultimately ineffective—it generates distress without generating solutions.

The content of rumination typically focuses on three interconnected themes: causes ("Why did this happen? What's wrong with me that caused this? What did I do to deserve this?"), meanings ("What does this say about me as a person? What do others think of me now? Am I fundamentally flawed?"), and consequences ("How will this affect my future? What other bad things will result from this? Is my life ruined?"). These questions rarely have satisfying answers, but the ruminating mind continues asking them compulsively, as if the next iteration might finally yield the insight that resolves the distress. Instead, each repetition strengthens the neural pathways encoding the negative experience and the associated emotional pain, making future rumination more likely and more automatic.

Why do we ruminate despite its obvious costs?

Rumination often arises from an understandable and even admirable desire to solve problems, make sense of negative experiences, or prepare for future challenges. It feels productive—it seems like we are "working on" the problem, doing something constructive about our distress. The mind mistakes mental activity for useful activity, confusing the intensity of our engagement with the productivity of our thinking. There may also be superstitious elements operating below conscious awareness: some people unconsciously believe that worrying about bad outcomes somehow prevents them or that relaxing vigilance would be dangerous and irresponsible. These beliefs are demonstrably false but remarkably persistent.

Research has firmly established that rumination is closely linked to and predictive of anxiety, depression, and chronic stress. Rather than resolving negative emotions as intended, rumination magnifies them, extending their duration and intensifying their impact on well-being. A distressing event that might have naturally faded from consciousness within hours instead occupies days or weeks of mental bandwidth, each repetition re-triggering the stress response and deepening the emotional wound rather than allowing it to heal. People who ruminate habitually experience worse mental health outcomes across virtually every measure, including higher rates of clinical depression, greater anxiety severity, reduced life satisfaction, and impaired problem-solving ability.

Rumination is like a hamster wheel in the mind—lots of motion generating the illusion of progress, but no actual movement forward. The brain keeps returning to the negative thought hoping to finally 'solve' it, but the repetition only strengthens the neural pathways that make the thought more likely to recur.

— Dr. Susan Nolen-Hoeksema

Neuroscientist Paul Andrews and others have described rumination as an attempt by the brain to analytically "solve" negative experiences—a kind of intensive processing mode that the brain enters in response to perceived problems requiring resolution. But because rumination typically focuses on problems that are not actually solvable through analysis alone—such as past events that cannot be changed, future uncertainties that cannot be eliminated, or existential questions that have no definitive answers—it becomes a mental trap that maintains indefinite suffering without the benefits of actual problem resolution. The analytical mode persists because the "problem" is never truly solved, creating a loop of unproductive mental activity that consumes enormous cognitive resources while producing only distress.

The Impact of Negative Thinking on Relationships

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Your brain's tendency to amplify negative thoughts does not operate in isolation within your own mind—it radiates outward, profoundly impacting your relationships with romantic partners, family members, friends, and professional colleagues. When your mind is habitually consumed with negative thinking patterns, it becomes all too easy to misinterpret others' neutral or even positive behavior, expect the worst from people who genuinely care about you, overreact to minor slights or misunderstandings, and create conflicts where none need exist. The negativity bias, originally evolved to protect us from external environmental threats, can transform into a relationship-damaging force that treats loved ones as potential adversaries and interprets ambiguous behavior through the most negative possible lens.

Relationship researchers have found that the negativity bias operates with particular power in intimate relationships, where we are emotionally vulnerable and therefore hypervigilant to potential threats to the bond. John Gottman's extensive research on marriage found that the ratio of positive to negative interactions needed for a relationship to thrive is approximately 5:1—five positive interactions for every single negative one. This striking ratio reflects the disproportionate psychological weight of negative interactions; a single moment of criticism, contempt, or dismissiveness can undo the relationship-building effects of multiple kind words, loving gestures, or supportive actions. Couples whose ratios fall below this threshold show declining relationship satisfaction over time and face significantly elevated risk of eventual separation or divorce.

Examples of How Negative Thinking Damages Relationships:

Mind Reading: Based on minimal or ambiguous evidence—a partner's fleeting facial expression, slightly different tone of voice, or brief silence—you assume you know their internal thoughts, which you presume are negative and directed at you. "She's upset with me." "He thinks I'm incompetent." "They're silently judging me." This assumed knowledge of others' mental states is almost always negative when the negativity bias is operating and is frequently completely wrong. Acting on these assumptions—becoming defensive, withdrawing emotionally, or preemptively attacking—creates real conflict that seems to confirm the negative expectations, even though the original assumption was entirely incorrect.

Negative Filtering: You focus predominantly or exclusively on your partner's flaws, mistakes, annoying habits, and disappointing moments while systematically overlooking their positive qualities, kind actions, efforts to please you, and moments of connection. Over time, this creates a mental portrait of your partner that dramatically overemphasizes the negative while minimizing or ignoring the positive, leading to decreased appreciation, increased criticism, erosion of affection, and deterioration of the goodwill that sustains relationships through difficult periods. Partners who feel consistently noticed only for their shortcomings become demoralized, defensive, and may eventually stop trying to please someone who seems impossible to satisfy.

Hostile Attribution Bias: You consistently interpret ambiguous behavior from others as intentionally harmful, deliberately hurtful, or reflective of negative feelings toward you rather than giving the benefit of the doubt that healthy relationships require. Your partner forgot to call not because they were genuinely busy and overwhelmed but because they don't care about you or your feelings. A friend's canceled plans reflect not legitimate schedule conflicts but deliberate rejection of your company. A colleague's brief email is intentional rudeness rather than simply time pressure. This pattern ensures that neutral or even positive behavior is experienced negatively, maintaining grievance and distrust regardless of others' actual intentions or behavior.

Resentment Accumulation: Holding onto negative thoughts about past grievances—mentally rehearsing every slight, cataloging every disappointment, repeatedly reviewing every way you have been wronged—allows resentment to accumulate like toxic sediment at the bottom of the relationship. Even issues that have been explicitly discussed, apologized for, and ostensibly resolved continue to poison the relationship from within, erupting in moments of stress or being added to an ever-growing mental list of complaints that eventually overwhelms any remaining positive feelings and makes continued connection feel impossible.

Over time, unchecked negative thinking can systematically erode the trust, communication, and intimacy that relationships need to survive and thrive. Partners begin to feel perpetually criticized regardless of their efforts, chronically misunderstood despite their attempts to communicate, or consistently unappreciated no matter what they contribute. This typically leads either to escalating conflict as they defend themselves against perceived unfairness or to emotional withdrawal as they protect themselves by disengaging from a relationship that has become painful. Either pattern signals serious relationship decline that, without conscious intervention, often culminates in separation or in a hollowed-out partnership that continues in legal form but lacks warmth, intimacy, or genuine connection.

Why Do Some People Struggle More with Negative Thoughts Than Others?

While all humans experience some degree of negativity bias—it is built into our species' fundamental neural architecture through millions of years of evolutionary pressure—the intensity of negative thinking varies substantially between individuals. Some people seem to recover quickly from setbacks, maintaining optimistic outlooks even after genuine disappointments, while others become mired in negative thoughts that resist all efforts at change. Understanding the factors that contribute to this individual variation helps both in understanding our own particular tendencies and in developing compassion for those who struggle more intensely with negativity through no fault of their own.

Childhood Experiences and Attachment Style

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

Early childhood experiences play a formative and lasting role in shaping how we perceive and process negative information throughout our entire lives. The developing brain is remarkably plastic during early childhood, meaning that early experiences literally shape its physical structure and functional patterns in ways that persist into adulthood. Children who experience consistent, responsive caregiving—whose needs for comfort, safety, stimulation, and connection are reliably met by attentive caregivers—develop what attachment researchers call secure attachment. These fortunate individuals tend to have more balanced emotional responses to stress, greater resilience to setbacks, more effective emotion regulation strategies, and less intense negativity bias because their early experiences taught them that the world is generally safe and that others can be trusted to provide support when needed.

In contrast, children who experienced neglect, harsh criticism, inconsistent caregiving, emotional unavailability, or outright abuse often develop insecure attachment styles—anxious, avoidant, or disorganized patterns of relating that persist into adulthood and shape all subsequent relationships. These individuals learned early that the world is fundamentally unpredictable or dangerous, that others may not be there when needed and cannot be fully trusted, and that constant vigilance is necessary for psychological and sometimes physical survival. This early learning creates heightened negativity bias that serves a protective function—if you expect the worst and prepare for it, you may be less devastated when bad things happen—but comes at the enormous cost of chronic anxiety, difficulty trusting others, persistent negative self-perception, and impaired ability to enjoy positive experiences when they occur.

Genetics and Brain Chemistry

There is substantial and growing evidence that some people are genetically predisposed to negativity or pessimism due to inherited variations in brain chemistry and neural structure. Neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and GABA play crucial roles in mood regulation, emotional processing, and stress responses. Genetic variations affecting these neurotransmitter systems—including genes that influence production, release, reuptake, and receptor sensitivity—can substantially influence baseline mood, emotional reactivity, sensitivity to stress, and speed of recovery from negative experiences. Low levels of serotonin, in particular, are strongly associated with increased negativity, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and difficulty experiencing pleasure from positive events.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone released by the adrenal glands, also varies substantially between individuals in ways that influence negativity. Some people have stress response systems that activate more readily and remain active longer, meaning they experience more intense and more prolonged stress reactions to negative events. This heightened stress reactivity can be partially genetic and partially shaped by early experiences (particularly early life stress, which can permanently calibrate the stress response system toward greater sensitivity). Over time, chronically elevated cortisol can actually damage brain structures involved in emotional regulation—particularly the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex—further intensifying negative thinking patterns in a vicious cycle where stress causes brain changes that increase subsequent stress reactivity.

Personality Traits

Certain personality traits, particularly the trait psychologists call neuroticism (one of the "Big Five" personality dimensions), are consistently and strongly associated with greater susceptibility to negative thinking. People high in neuroticism experience emotions more intensely, particularly negative emotions like anxiety, sadness, anger, guilt, and irritability. They are more sensitive to potential threats in their environment, more prone to worry about future possibilities, more likely to interpret ambiguous situations in negative ways, and slower to recover from negative emotional experiences. This trait has substantial genetic heritability but is also influenced by life experience, and it creates a persistent undercurrent of negativity that colors perception of virtually all experience and makes positive reframing more cognitively difficult.

Stress and Mental Health Conditions

Chronic stress, anxiety disorders, depression, and other mental health conditions both result from and contribute to negative thinking patterns, creating feedback loops that can be extremely difficult to escape without professional intervention. When we are stressed, anxious, or depressed, the brain becomes more sensitive to negative stimuli and simultaneously less responsive to positive ones—the negativity bias intensifies precisely when we most need balance and perspective. This heightened sensitivity makes it harder to notice positive events that are actually occurring, harder to experience pleasure from activities that normally bring joy (a phenomenon called anhedonia), and harder to maintain the cognitive flexibility needed to reframe negative interpretations in more balanced ways. The brain in a stressed or depressed state is essentially tuned to detect and amplify negativity while screening out positivity, creating a self-maintaining pattern of suffering.

Breaking Free from Negative Thinking: Strategies for a Healthier Mind

While the brain is naturally inclined to amplify negative thoughts through mechanisms refined over millions of years of evolution, this ancient programming is not destiny. The same neuroplasticity that allowed our brains to develop these patterns in response to environmental pressures allows them to be modified through deliberate practice in different directions. It is genuinely possible to train your mind to adopt a more balanced, realistic, and even positive perspective—not through denial of genuine problems, forced artificial positivity, or suppression of legitimate negative emotions, but through systematic practices that gradually rewire neural pathways and develop new cognitive habits that better serve our wellbeing in the modern world. Here are evidence-based strategies that research has shown to effectively reduce negative thinking:

Mindfulness and Meditation

Mindfulness is the practice of focusing attention on the present moment without judgment, observing thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they arise without trying to change them, suppress them, or getting swept away by their content. This simple-sounding practice is remarkably powerful for addressing negative thinking because it creates crucial space between stimulus and response, allowing recognition of negative thought patterns before they trigger automatic emotional reactions and behavioral responses. By becoming more aware of your thoughts as mental events—temporary patterns of neural activity that arise and pass away—rather than absolute truths about reality that demand immediate response, you can recognize when you are falling into negativity and consciously choose a different relationship to those thoughts.

Meditation has been extensively studied and shown to reduce rumination, lower baseline stress hormones, decrease amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli, improve emotional regulation capacity, and actually change brain structure in ways that support psychological well-being over time. Brain imaging studies show that experienced meditators have increased gray matter density in areas associated with emotional regulation, perspective-taking, and executive function, along with decreased activity and reduced size in the amygdala, the threat-detection center that drives the negativity bias. These structural brain changes suggest that meditation practice produces lasting modifications to the neural hardware underlying emotional processing, not merely temporary shifts in mental state.

How to Practice Mindfulness:

- Set aside a few minutes each day—even five to ten minutes can be beneficial when practiced consistently—to sit quietly in a comfortable position with eyes closed or softly focused

- Direct your attention to your breath, noticing the physical sensations of air entering and leaving your body, the rise and fall of your chest or belly, without trying to control or change the breathing

- When thoughts arise—including negative thoughts, which will certainly occur—notice them without judgment, as if watching clouds pass across the sky or leaves float down a stream, then gently return attention to the breath

- Gradually extend practice duration over weeks and months, and bring mindful awareness to daily activities like eating, walking, listening, or working

- When you notice yourself caught in negative thinking patterns during daily life, use the mindfulness skill of stepping back and observing rather than being consumed by the thought content

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

CBT is one of the most extensively researched and consistently effective therapeutic approaches for addressing negative thinking patterns, with hundreds of controlled studies supporting its efficacy for depression, anxiety, and related conditions. Developed by psychiatrist Aaron Beck in the 1960s, CBT is based on the fundamental insight that our emotional responses are shaped not directly by external events themselves but by our interpretations of those events—and that these interpretations can be systematically examined, tested against evidence, and modified when they prove inaccurate or unhelpful. CBT works by helping you identify the specific cognitive distortions operating in your thinking, challenge their accuracy with logical analysis and real-world evidence, and develop more realistic and balanced alternatives that better fit the actual facts.

Key CBT Techniques:

Thought Records: When you notice a negative emotion arising, write down the specific situation that triggered it, the automatic thought that arose in response, the cognitive distortion or distortions involved, the emotions you experienced and their intensity, and then systematically challenge the thought by examining evidence both for and against it. Finally, generate a more balanced alternative thought that accounts for all the evidence. This systematic process, repeated consistently over time, builds the cognitive habit of questioning rather than automatically accepting negative interpretations.

Cognitive Restructuring: Identify recurring distorted thinking patterns in your life—perhaps you tend toward catastrophizing about health, overgeneralizing about social rejection, or engaging in black-and-white thinking about work performance—and practice systematically replacing these patterns with more balanced thoughts. For example, if you tend toward catastrophizing, deliberately practice generating best-case and most-likely scenarios alongside worst-case ones. If you overgeneralize, practice actively finding exceptions, nuances, and complexities that the generalizing thought ignores.

Behavioral Experiments: Rather than simply arguing against negative predictions intellectually, test them by actually engaging in the feared situation and observing what happens in reality. Often our negative predictions fail to materialize, providing experiential evidence that counteracts distorted thinking more powerfully than verbal challenging alone can achieve. A person who believes "everyone will think I'm stupid if I speak up in meetings" can test this prediction by actually speaking up and then carefully observing others' actual responses.

Gratitude Practice

Deliberately focusing on gratitude can help counterbalance the brain's negativity bias by actively and repeatedly directing attention to positive aspects of life that would otherwise go unnoticed, be quickly forgotten, or be dismissed as unimportant. Because of the negativity bias, positive experiences need extra attention and processing to have lasting impact on our mood, memory, and overall sense of well-being. Gratitude practices provide this extra attention, helping to correct the systematic imbalance between how thoroughly we process negative versus positive information. Research consistently shows that practicing gratitude improves mental well-being, increases positive emotions, enhances relationship satisfaction, improves sleep quality, and reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety.

How to Practice Gratitude:

- Keep a daily gratitude journal, writing three to five specific things you are genuinely thankful for each day—they can be small everyday things like a delicious meal, a moment of connection, or pleasant weather, or larger things like supportive relationships, meaningful work, or good health

- Be as specific and detailed as possible rather than general and abstract: "I'm grateful that my partner noticed I was stressed and made me tea without being asked" is more powerful than "I'm grateful for my partner"

- Express appreciation directly to people who have helped you, supported you, or made your life better in some way, either in person, by phone call, or in a written letter

- Throughout the day, pause periodically to notice and mentally acknowledge positive moments, pleasant sensations, or things going well that you might otherwise take for granted

- When negative thoughts arise, consciously and deliberately shift attention to something you can genuinely appreciate as a counterbalance

Positive Affirmations and Self-Compassion

Our internal dialogue—the constant stream of self-talk that accompanies our experience—significantly shapes our emotional state and self-perception, and many people maintain a harsh, critical inner voice that reinforces negative self-perception and contributes to depression and anxiety. Positive affirmations can help gradually rewire this habitual self-talk by deliberately repeating self-empowering beliefs until they begin to feel natural and automatic. Self-compassion, a concept developed and researched extensively by psychologist Kristin Neff, involves treating yourself with the same kindness, understanding, and patience you would offer to a good friend who was struggling, rather than the harsh criticism many people reflexively direct at themselves.

How to Practice Self-Compassion:

- When you notice negative self-talk arising, pause and ask yourself: "What would I say to a close friend who was in this same situation and feeling this way?" Then deliberately offer yourself that same kindness rather than criticism

- Acknowledge your struggles and painful feelings without judgment, recognizing that suffering and imperfection are part of the universal human experience rather than personal failings that separate you from others and prove your unworthiness

- Practice self-soothing physical touch during difficult moments (such as placing a hand gently on your heart) combined with kind self-talk, activating the body's caregiving system

- Replace harsh self-criticism with more supportive self-statements: "This is really difficult right now, and it's okay to struggle" rather than "I'm such an idiot for feeling this way"

- Use affirmations that feel authentic and achievable rather than forced and unrealistic—statements you can genuinely move toward believing with consistent practice

Limit Negative Inputs

The information you consume through news media, social networks, entertainment, and interpersonal relationships has a significant cumulative impact on your thoughts, emotional state, and overall mental health. We live in an unprecedented era of constant access to information, much of it deliberately selected and presented to be negative because bad news reliably attracts more attention, generates more engagement, and spreads more widely than good news. Constant exposure to negative information overwhelms the brain with threat signals, maintains chronically elevated stress hormones, and reinforces the negativity bias by providing endless examples of things going wrong in the world. Deliberately managing information intake is an essential component of mental health maintenance.

How to Limit Negative Inputs:

- Set specific, bounded limits around news consumption—perhaps checking once or twice daily at designated times rather than continuously throughout the day

- Carefully curate your social media feeds to reduce exposure to content that triggers negative comparison, outrage, anxiety, or distress, unfollowing or muting accounts that consistently worsen your mood

- Choose news sources that provide balanced, contextualized coverage and include constructive solutions, not just sensationalized problems and crises

- Be intentional about the people you spend time with, prioritizing relationships with those who support, encourage, and uplift you while limiting exposure to consistently negative, critical, or draining individuals

- Actively seek out content that inspires, educates, entertains positively, or brings genuine joy rather than passively consuming whatever algorithms serve

- Create technology-free times and spaces where your attention can rest from the constant stimulation of digital information

The Power of Neuroplasticity: Rewiring Your Brain for Positivity

Author: Evan Miller;

Source: psychology10.click

One of the most exciting and empowering discoveries in modern neuroscience is the brain's remarkable ability to change and adapt throughout the entire lifespan, a phenomenon called neuroplasticity. Contrary to earlier scientific beliefs that the brain was essentially fixed and unchangeable after childhood development was complete, we now have overwhelming evidence that the brain continuously rewires itself in response to experience, attention, learning, and deliberate practice at every age. This means that even deeply ingrained patterns of negative thinking that have persisted for decades can genuinely be changed—not easily or quickly, but meaningfully and lastingly—through consistent effort in the right directions over sufficient time.

Every thought you think creates or strengthens neural pathways, and thoughts you repeat frequently become deeply worn channels through which future thoughts automatically flow. If you have spent years or decades thinking predominantly negative thoughts, those neural pathways are strong, well-established, and deeply entrenched, and your thoughts naturally and effortlessly flow toward negativity without conscious effort or intention. But with consistent, patient practice of the techniques described throughout this article—mindfulness, cognitive restructuring, gratitude, self-compassion, and managed information intake—you can gradually create new neural pathways that make balanced and positive thinking increasingly automatic and natural over time.

The key to harnessing neuroplasticity is consistency sustained over time. Just as physical exercise produces meaningful results only through regular practice over weeks and months rather than occasional intense sessions, mental exercises require sustained effort before producing lasting structural change in the brain. Brief experiments with gratitude journaling or occasional meditation sessions, while certainly better than nothing, will not produce the neural rewiring that genuinely transforms habitual thought patterns. Committing to daily practice for months—not days or weeks—allows new neural pathways to strengthen to the point where they can compete effectively with established negative patterns and eventually become the default mode of processing experience.

Conclusion: Taking Control of Your Mental Landscape

Negative thoughts are a natural part of the human experience, rooted in brain mechanisms that evolved over millions of years to keep our ancestors alive in genuinely dangerous environments filled with predators, competitors, and unpredictable threats to survival. Understanding this evolutionary heritage helps us recognize that our tendency toward negativity is not a personal flaw, character defect, or sign of weakness but a universal human characteristic with understandable origins that we all share. At the same time, this understanding empowers us to recognize that these ancient mechanisms, however well they served our ancestors, do not have to control our modern lives—we have the remarkable capacity, through deliberate practice and sustained effort, to reshape our mental landscape toward greater balance, resilience, and authentic well-being.

The negativity bias served crucial survival functions for our prehistoric ancestors, helping them detect and respond to genuine threats quickly enough to survive another day. But in the contemporary world, where most of us face few genuine physical threats to survival, this same bias often creates psychological suffering vastly disproportionate to actual dangers. By implementing the strategies explored throughout this article—mindfulness to create space between thoughts and automatic reactions, cognitive restructuring to challenge distorted interpretations with evidence, gratitude to deliberately attend to the positive experiences we naturally overlook, self-compassion to soften our harsh inner critic, and careful curation of our informational environment—we can shift our perception from systematic focus on what's wrong toward a more balanced, accurate view that includes what's right alongside what's challenging.

Ultimately, while the brain's negativity bias is real, powerful, and deeply embedded in our neural architecture, it does not need to dictate your thoughts, feelings, relationships, or life trajectory. The brain that creates the problem also possesses the remarkable capacity to solve it, through the gift of neuroplasticity that allows us to reshape our neural architecture through consistent practice throughout our entire lives. With patience, persistence, and self-compassion for the inevitable setbacks and difficulties along the way, you can train your brain to find greater balance, develop genuine resilience in the face of life's challenges, and experience more frequent moments of authentic joy, connection, and meaning—even in a world that presents plenty of legitimate reasons for concern. The negativity bias helped our ancestors survive; understanding and working skillfully with it helps us thrive.

This article provides general information about the psychology and neuroscience of negative thinking and is not intended as professional psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you are experiencing persistent negative thoughts, depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns that significantly impact your daily functioning, quality of life, or relationships, please consult with a qualified mental health professional for personalized assessment and evidence-based treatment.

Questions and Answers: Why Your Brain Amplifies Negative Thoughts

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.