Effective Strategies for Managing Anxiety: Physical Activity, Breathing Exercises, and More

Content

Content

Anxiety is a prevalent mental health condition characterized by feelings of worry, nervousness, or fear that are strong enough to interfere with one's daily activities, affecting approximately 284 million people worldwide and representing one of the most common mental health challenges of our time. Unlike ordinary stress or worry that most people experience occasionally, clinical anxiety persists over time, often intensifying rather than resolving, and can significantly impair functioning across multiple domains of life including work, relationships, and physical health. The experience of anxiety varies considerably between individuals—some may feel a constant low-level hum of worry that never quite subsides, while others experience intense episodes of acute anxiety that arrive suddenly and feel overwhelming, and still others cycle between periods of relative calm and periods of heightened distress.

Common symptoms of anxiety include restlessness and an inability to sit still or relax, increased heart rate and palpitations that may feel like the heart is racing or pounding, rapid breathing or shortness of breath that can sometimes escalate to hyperventilation, excessive sweating even in comfortable temperatures, trembling or shaking that may be visible or felt internally, and profound fatigue that seems disproportionate to actual physical exertion. The physical symptoms of anxiety are not imaginary or exaggerated—they represent real physiological changes as the body's stress response system activates, preparing for threat even when no genuine danger exists. This activation involves the release of stress hormones including cortisol and adrenaline, increased activity in the sympathetic nervous system, and changes in blood flow, muscle tension, and digestive function that produce the uncomfortable sensations anxiety sufferers know all too well.

Beyond these physical manifestations, anxiety frequently leads to troubles with concentration, as the anxious mind struggles to focus on tasks when constantly scanning for potential threats or ruminating on worries. Sleep disturbances are extremely common among those with anxiety—difficulty falling asleep as the mind races through concerns, difficulty staying asleep due to nighttime awakening with worry, or early morning awakening with immediate activation of anxious thoughts. The relationship between anxiety and sleep is bidirectional: anxiety disrupts sleep, and poor sleep increases vulnerability to anxiety, creating a cycle that can be difficult to break without deliberate intervention. Cognitive symptoms may also include excessive worry about multiple areas of life, difficulty controlling worried thoughts, expecting the worst outcomes even when evidence suggests otherwise, and perceiving situations as more threatening than they actually are.

The causes of anxiety are multifactorial, involving complex interactions between genetic predisposition, brain chemistry and structure, personality factors, and life experiences. Research suggests that anxiety disorders run in families, indicating a heritable component, though genes alone do not determine who will develop anxiety—environmental factors play crucial roles in whether genetic vulnerability becomes expressed as actual disorder. Early life experiences, particularly those involving threat, unpredictability, or inadequate support, can shape the developing brain and nervous system in ways that increase anxiety vulnerability throughout life. Chronic stress, traumatic experiences, major life transitions, and ongoing difficult circumstances can all contribute to the development or worsening of anxiety symptoms.

The Role of Physical Activity in Managing Anxiety

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Engaging in regular physical activity is a proven strategy to alleviate symptoms of anxiety, with research consistently demonstrating that exercise can be as effective as medication for some individuals and serves as a valuable complement to other treatments for most. The relationship between physical activity and mental health has been recognized for millennia—ancient physicians prescribed walking and other physical activities for melancholy and nervous conditions—but modern science has illuminated the specific mechanisms through which movement benefits the anxious mind and body. Understanding these mechanisms can increase motivation to exercise and help individuals select activities most likely to benefit their particular presentation of anxiety.

Exercise releases endorphins, natural brain chemicals that can enhance your sense of well-being and produce what is sometimes called the "runner's high"—a state of elevated mood, reduced pain perception, and general euphoria that can follow sustained physical activity. These endorphins interact with opioid receptors in the brain, producing effects similar to (though milder than) opioid drugs, naturally reducing pain and promoting positive feelings. Beyond endorphins, exercise influences multiple neurotransmitter systems relevant to anxiety, including serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), all of which play roles in mood regulation and anxiety.

Exercise is the most underutilized antidepressant and anxiolytic treatment available. It affects the same neurotransmitter systems as our most effective medications, but without the side effects and with numerous additional health benefits that medications cannot provide.

— Dr. John Ratey

Moreover, physical activity serves as a distraction, allowing you to find some quiet time to break out of the cycle of negative thoughts that feed anxiety. When engaged in exercise, particularly exercise that requires attention and coordination, the mind has less capacity available for worry and rumination. This temporary respite from anxious thoughts can interrupt the self-reinforcing cycle where worry leads to more worry, providing a natural break that allows the nervous system to reset. For many people, the hour spent exercising becomes the only hour of the day when they are not actively worrying, making exercise a crucial sanctuary from the relentless pressure of anxious thoughts.

Physical activity also provides exposure to the physical sensations of arousal—increased heart rate, sweating, heavy breathing—in a context where they are expected and appropriate. For individuals with anxiety, particularly panic disorder, these sensations often trigger fear because they are associated with anxiety attacks. By repeatedly experiencing these sensations during exercise without negative consequences, individuals can learn that elevated heart rate and breathing do not necessarily signal danger, reducing the fear of physical symptoms that maintains many anxiety conditions. This process, sometimes called interoceptive exposure, can be a powerful component of anxiety treatment.

The autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions including heart rate, breathing, and digestion, becomes better regulated through regular exercise. The autonomic nervous system has two main branches: the sympathetic nervous system, which activates the stress response, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which promotes rest and recovery. Anxiety is associated with excessive sympathetic activation and insufficient parasympathetic activity. Regular exercise trains both branches, improving the body's ability to activate appropriately when needed and, crucially, to deactivate and return to calm when the stressor has passed. This improved autonomic flexibility means that regular exercisers recover more quickly from stress and are less likely to remain in prolonged states of anxiety.

Numerous studies demonstrate the efficacy of exercise in improving mental health, reducing anxiety, and increasing resilience to stress. A meta-analysis examining the effects of exercise on anxiety found that regular physical activity reduces anxiety symptoms by approximately the same amount as medication, with effects that persist as long as exercise continues. Importantly, these benefits appear across different types of exercise, different intensities, and different populations, suggesting that the key factor is simply moving the body regularly rather than following any specific prescription. This flexibility means that individuals can choose activities they enjoy and are likely to maintain, rather than forcing themselves through exercises they dislike.

Breathing Exercises

Breathing exercises are a cornerstone of anxiety reduction, offering a quick and effective way to calm the mind and reduce stress that can be practiced anywhere, at any time, without any equipment or special preparation. The breath occupies a unique position in human physiology: it is controlled automatically by the brainstem, continuing without conscious attention, yet it can also be consciously controlled and modified. This dual nature makes breathing a bridge between the voluntary and involuntary nervous systems, providing a point of access through which we can influence bodily functions that are normally outside conscious control—including heart rate, blood pressure, and the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system activity.

The connection between breathing and emotional state is bidirectional and powerful. When we are anxious, breathing naturally becomes rapid and shallow, concentrated in the upper chest rather than the lower lungs and diaphragm. This breathing pattern is part of the body's preparation for action—quick breaths can rapidly oxygenate blood for fighting or fleeing. However, this breathing pattern also signals to the brain that danger is present, maintaining or intensifying the anxiety state even when no actual threat exists. By deliberately changing breathing patterns, we can send different signals to the brain, activating the parasympathetic nervous system and promoting calm.

Deep Breathing

Deep breathing, also known as diaphragmatic breathing or belly breathing, involves breathing deeply from the diaphragm rather than shallowly from the chest, maximizing oxygen intake and carbon dioxide elimination while activating the vagus nerve, which promotes parasympathetic activity and calm. This technique is simple in concept but requires practice to master, as many anxious individuals have developed habitual shallow breathing patterns that feel normal even though they contribute to anxiety. With practice, deep breathing can become a powerful tool for managing anxiety in the moment and, practiced regularly, can shift baseline nervous system function toward greater calm.

Find a comfortable position: Sit in a comfortable chair with your back straight and feet flat on the floor, or lie flat on the floor or a bed with a pillow under your knees for support. The position should allow your abdomen to expand freely without restriction from tight clothing or awkward posture.

Place your hands: Put one hand on your chest and the other on your stomach, just below your ribcage. These hand positions will provide feedback about where your breath is going, helping you learn to direct it to the diaphragm.

Inhale slowly: Breathe in slowly through your nose over a count of four to six seconds, ensuring that your stomach moves out against your hand while the hand on your chest remains as still as possible. The goal is to fill the lower lungs first, causing the diaphragm to descend and push the abdomen outward. If the chest rises significantly while the belly stays still, the breath is too shallow.

Hold the breath: Hold your breath briefly for a count of one to two seconds, allowing oxygen to fully transfer to the blood and creating a moment of stillness.

Exhale slowly: Exhale slowly through pursed lips, like whistling or blowing through a straw, while allowing your abdominal muscles to gently contract. The hand on your stomach should move in as you exhale, but your other hand should move very little. The exhale should be slightly longer than the inhale—if you inhaled for four counts, exhale for six counts.

Repeat: Continue this pattern of deep breathing for several minutes, ideally five to ten minutes for a full practice session. With each breath, try to make the breathing slower, deeper, and more relaxed. If the mind wanders to worries, gently return attention to the physical sensations of breathing.

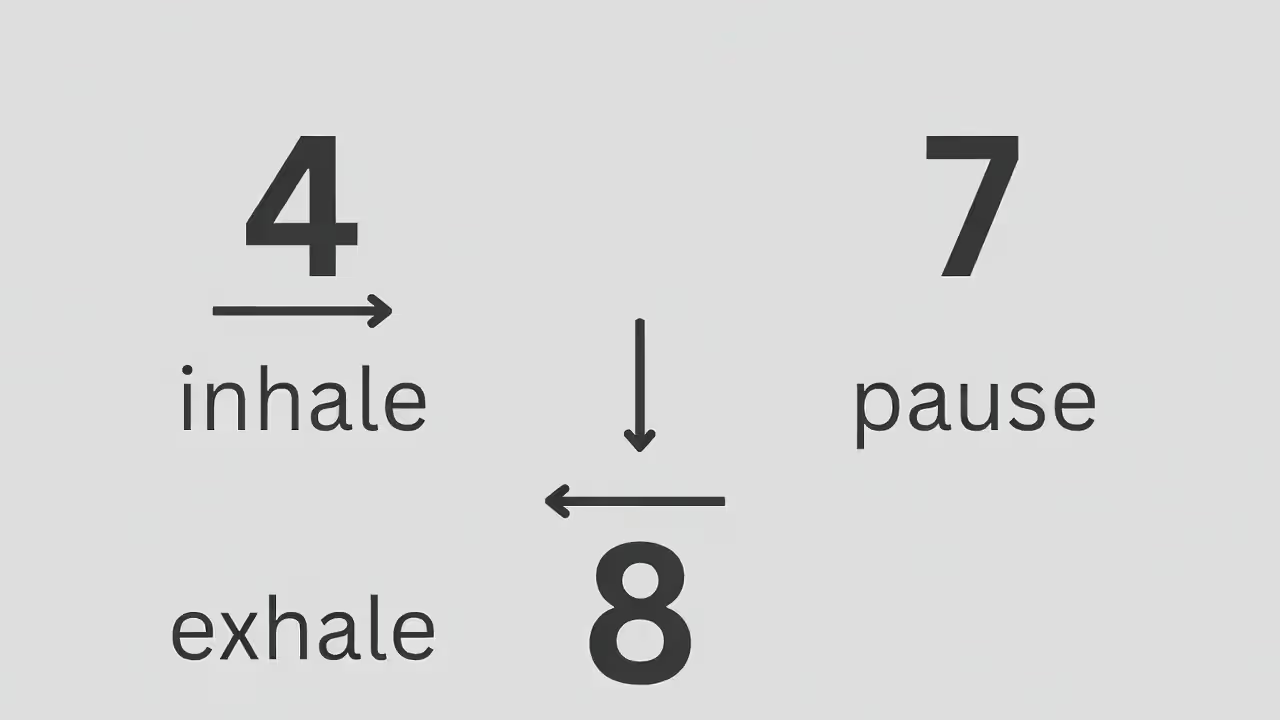

4-7-8 Breathing Technique

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Developed by Dr. Andrew Weil based on ancient yogic breathing practices, the 4-7-8 breathing technique is simple, easy to learn, and can be done anywhere, making it accessible for use in anxious moments. It is particularly effective for reducing anxiety quickly and helping individuals fall asleep when anxious thoughts are interfering with rest. The specific timing of this technique—relatively short inhale, long hold, extended exhale—maximizes parasympathetic activation and can produce noticeable calm within just a few breath cycles.

Prepare: Sit or lie in a comfortable position with your spine relatively straight. Place the tip of your tongue against the tissue ridge behind your upper front teeth, and keep it there throughout the practice. This tongue position may feel awkward initially but becomes natural with practice.

Exhale: Begin by exhaling completely through your mouth around your tongue, making a whoosh sound as the air leaves. This complete exhale empties the lungs and prepares for a full, deep inhale.

Inhale: Close your mouth and inhale quietly through your nose to a mental count of four. The inhale should be comfortable and complete but not strained.

Hold your breath: Hold your breath for a count of seven. This extended hold allows for maximum oxygen transfer and activates the parasympathetic nervous system. If seven counts feels too long initially, the entire pattern can be shortened while maintaining the 4:7:8 ratio.

Exhale completely: Exhale completely through your mouth, making a whoosh sound, to a count of eight. The extended exhale is the most important part of the technique for anxiety reduction, as long exhales strongly activate the vagus nerve and parasympathetic system.

Repeat: This is one breath cycle. Repeat the cycle three more times for a total of four breaths. The entire practice takes only about two minutes but can produce significant anxiety reduction.

Benefits of Breathing Exercises for Calming the Mind

Breathing exercises like these can have a profound impact on the nervous system by activating the parasympathetic nervous system, which induces a state of calmness often called the "relaxation response." This activation occurs through multiple mechanisms: the vagus nerve, which connects the brain to many organs including the heart and lungs, is stimulated by slow, deep breathing, particularly by extended exhales; carbon dioxide levels in the blood increase slightly during breath holds and slow breathing, which paradoxically promotes calm; and the rhythmic, repetitive nature of breathing exercises focuses the mind, reducing the cognitive processing available for worry.

Regular practice of breathing exercises can help manage the physiological symptoms of anxiety by training the nervous system to shift more easily from sympathetic to parasympathetic dominance. Over time, individuals who practice breathing exercises regularly often find that their baseline anxiety decreases and that they recover more quickly from anxious episodes. The benefits are dose-dependent—more practice generally produces greater effects—but even brief daily practice can produce noticeable improvements.

Breathing exercises also help to shift focus from anxious thoughts to controlled breathing, aiding in mindfulness and present-moment awareness. When attention is fully absorbed in the physical sensations of breathing—the movement of the abdomen, the feeling of air entering and leaving the nostrils, the rhythm of inhale and exhale—there is less attention available for worry about the future or rumination about the past. This shift in attention is a core component of mindfulness practice and can provide relief from the relentless mental activity that characterizes anxiety.

Aerobic Exercises

Aerobic exercise, characterized by sustained physical activity that increases heart rate and breathing over an extended period, is not only beneficial for physical health but also plays a significant role in improving mental health by reducing anxiety and depression. The term "aerobic" refers to the use of oxygen to meet energy demands during exercise, distinguishing these activities from short-burst anaerobic exercises like sprinting or weightlifting. Common aerobic exercises include walking, running, cycling, swimming, dancing, and many others that can be sustained for twenty minutes or more at moderate intensity.

The mechanisms through which aerobic exercise reduces anxiety are multiple and complementary. Neurobiologically, aerobic exercise increases the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that supports the survival of existing neurons and encourages the growth of new neurons, particularly in the hippocampus—a brain region important for memory and emotional regulation that tends to be smaller in people with anxiety and depression. Aerobic exercise also increases blood flow to the brain, delivering oxygen and nutrients that support optimal brain function. Changes in neurotransmitter systems, including increased serotonin and endocannabinoid activity, contribute to mood improvement and anxiety reduction.

The evidence for exercise in treating anxiety is so strong that if exercise were a pill, it would be the most prescribed medication in psychiatry. We need to start thinking of physical activity as a legitimate medical treatment, not just a lifestyle recommendation.

— Dr. Madhukar Trivedi

Walking

Taking a brisk walk, especially in a natural environment, can substantially boost your mood while being accessible to almost everyone regardless of fitness level. Walking requires no special equipment beyond comfortable shoes, can be done almost anywhere, and can be easily integrated into daily life through commuting, lunch breaks, or evening strolls. For those new to exercise or returning after a period of inactivity, walking provides an excellent starting point that can gradually build toward more vigorous activities if desired.

Studies have shown that walking in nature reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex region associated with rumination—the repetitive thinking about negative emotions and experiences that characterizes much anxiety and depression—which can help lower symptoms of anxiety significantly. The combination of physical movement, natural scenery, and time away from screens and artificial environments appears to be particularly powerful for mental health. Even a single walk in nature can produce measurable improvements in mood and reductions in anxious thoughts.

Reduction in stress: Natural settings can decrease cortisol levels, the body's primary stress hormone, more effectively than equivalent exercise in urban or indoor environments. The visual complexity of natural scenes, the sounds of birds and rustling leaves, and the fresher air all contribute to stress reduction through mechanisms that researchers are still working to fully understand.

Enhanced mood: Exposure to sunlight during walks can increase serotonin levels, which improves mood and feelings of happiness while also helping to regulate circadian rhythms that affect sleep and overall well-being. Morning walks may be particularly beneficial for mood, as early light exposure helps set circadian rhythms for the day.

Improved self-perception: Regular walking can enhance self-esteem and reduce feelings of social withdrawal by providing a sense of accomplishment and self-efficacy. The simple act of taking care of oneself through exercise sends a positive message to the self, counteracting the self-neglect and withdrawal that often accompany anxiety.

Running

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Jogging or running regularly can be an excellent way to manage stress and anxiety, providing more intense physiological effects than walking while remaining accessible to many people with moderate fitness. The physical activity involved in running triggers robust release of endorphins, also known as the body's "feel-good" hormones, which act as natural painkillers and mood elevators, producing the well-known "runner's high" that many runners describe as a sense of euphoria, calm, and well-being following a run.

Running also helps to lower the levels of adrenaline and cortisol, which are stress hormones that remain elevated during chronic anxiety and contribute to many of its unpleasant symptoms, thus promoting a more relaxed state. The immediate post-run period is often characterized by significant calm and reduced anxiety, and these benefits can persist for hours or even days with regular running practice.

Increased brain health: Running can lead to the growth of new brain cells (neurogenesis) in the hippocampus, improving brain performance, memory, and emotional regulation while decreasing anxiety. This neurogenesis appears to be dose-dependent, with more running producing greater effects, though even modest amounts of running can produce measurable brain changes.

Stress relief: The repetitive, rhythmic motion of running can have a meditative effect on the brain, helping to calm the mind and reduce the intrusive thoughts that characterize anxiety. Many runners report that the rhythmic nature of running allows them to enter a mental state similar to meditation, where thoughts flow more freely and problems seem more manageable.

Improved sleep: Regular runners often experience better sleep quality, including falling asleep more quickly, sleeping more deeply, and feeling more rested upon waking, which is crucial for reducing anxiety since sleep deprivation significantly worsens anxiety symptoms.

Cycling

Cycling regularly, whether outdoors on roads and trails or indoors on a stationary bike, can improve mental health by reducing feelings of stress, depression, and anxiety through mechanisms similar to other aerobic exercises but with some unique advantages. Cycling combines physical exercise with the possibility of outdoor exposure, exploration of new areas, and, for outdoor cycling, the engaging task of navigating traffic or terrain that occupies attention and reduces rumination.

Enhanced cognitive function: Cycling helps build new brain cells in the hippocampus—the area of the brain responsible for memory and learning—and improves overall cognitive function through increased blood flow and neurotrophic factors, benefits that extend to emotional processing and anxiety regulation.

Stress reduction: Similar to running, cycling can decrease the body's stress hormones while increasing endorphins and other mood-enhancing neurochemicals, producing both immediate post-ride calm and longer-term reductions in baseline anxiety with regular practice.

Social interaction: Group rides and cycling clubs offer social benefits that can reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation, which often accompany anxiety. The cycling community tends to be welcoming to newcomers, and the shared experience of riding provides natural conversation topics that can ease social anxiety.

Yoga

Yoga combines physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditation to enhance both physical and mental health in an integrated practice that has been developed and refined over thousands of years. This ancient practice, which originated in India as a spiritual discipline, has been extensively adapted for modern secular contexts while retaining its effectiveness for managing stress, anxiety, and other mental health challenges. Modern research has validated many traditional claims about yoga's benefits, demonstrating measurable effects on stress hormones, brain function, and psychological well-being.

Introduction to Yoga

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Yoga is an ancient practice designed to bring together physical and mental disciplines to achieve peacefulness of body and mind, a state the ancient yogis called "union"—the literal meaning of the Sanskrit word "yoga." The practice helps manage stress and anxiety through multiple mechanisms: relaxation of chronically tense muscles, calming of the breath, focusing of the mind on present-moment sensations rather than past or future concerns, and cultivation of a different relationship to one's thoughts and emotions. Unlike purely physical exercise, yoga explicitly addresses mental and emotional states, making it particularly well-suited for anxiety management.

The physical practice of yoga involves assuming and holding specific postures, called asanas, which stretch and strengthen muscles, improve balance and flexibility, and require focused attention. The process of holding challenging postures while maintaining calm breathing teaches practitioners to remain calm and focused even when experiencing discomfort—a skill that transfers directly to managing the discomfort of anxiety. The practice promotes the release of physical tension, particularly in areas like the neck, shoulders, and jaw where stress commonly accumulates, providing direct relief from some of anxiety's physical manifestations.

Yoga has become increasingly popular worldwide as a method for maintaining wellness and combating various mental health issues, with hundreds of millions of practitioners and growing scientific support for its benefits. Different styles of yoga emphasize different aspects of practice—some focus primarily on physical postures, others on breathing, others on meditation—and range from gentle and restorative to physically demanding. This variety means that individuals can find styles suited to their needs, preferences, and physical capabilities, making yoga accessible to people across a wide range of ages and fitness levels.

Key Poses

Certain yoga poses are particularly beneficial for easing anxiety because they activate the parasympathetic nervous system, release physical tension, promote grounding and body awareness, or combine several of these benefits.

1. Child's Pose (Balasana)

Purpose: This resting pose centers, calms, and soothes the brain, making it a therapeutic posture for relieving stress and anxiety. The forward fold with head supported sends signals of safety to the nervous system, while the curled position is naturally comforting and protective.

How to Do It: Kneel on the floor with your big toes touching and sit back on your heels. Separate your knees about as wide as your hips—or keep them together for a more compact variation. As you exhale, lay your torso down between your thighs, allowing your forehead to rest on the floor or a prop like a pillow or yoga block. Lay your hands on the floor alongside your torso, palms up, and release the fronts of your shoulders toward the floor. Feel the weight of your shoulders pulling the shoulder blades wide across your back. Remain in this pose for one to several minutes, breathing slowly and allowing the body to release tension with each exhale.

2. Warrior Pose (Virabhadrasana)

Purpose: This powerful standing pose increases stamina, relieves stress, and stabilizes the body while promoting feelings of strength and confidence. The grounded stance and expansive arm position counteract the collapsed, protective postures that anxious people often assume.

How to Do It: Stand with legs three to four feet apart, turning your right foot out 90 degrees and left foot in slightly, about 15 degrees. Align the right heel with the left heel. Extend your arms out to the sides, parallel to the floor, with palms facing down. Exhale and bend your right knee over your right ankle, so that your shin is perpendicular to the floor and the thigh approaches parallel. Keep the left leg strong and straight. Reach actively through both arms, feeling energy extending through the fingertips. Turn your gaze to the right and hold for up to one minute, breathing steadily. Repeat on the opposite side.

3. Tree Pose (Vrikshasana)

Purpose: This balancing pose helps improve focus and concentration while calming the mind, as the attention required to maintain balance leaves little cognitive capacity for worry. The upward reach and steady standing promote feelings of dignity and stability.

How to Do It: Stand erect with arms at your sides. Shift your weight onto your left foot, grounding firmly through all four corners of the foot. Bend your right knee and place the right foot on the inner left thigh, calf, or ankle—never on the knee joint. The sole should be placed firm and flat against the leg. Keep your left leg straight and find your balance. When you feel stable, take a deep breath in and gracefully raise your arms over your head from the side, bringing your palms together or keeping them shoulder-width apart. Look straight ahead at a fixed point to help maintain balance. Hold and continue with gentle long breaths for 30 seconds to one minute. Release and repeat on the other side.

Mindfulness and Meditation

Integrating mindfulness into yoga practice involves maintaining a moment-by-moment awareness of body movements, breathing, and sensations, fully inhabiting the present experience rather than going through the motions while the mind wanders elsewhere. This mindful approach significantly enhances yoga's benefits by creating deeper engagement with the present moment, thereby helping to quiet the anxious mind's tendency to project into an uncertain future or replay regretted past events.

Enhanced focus: Mindfulness teaches you to concentrate on the present—on the sensations of stretch and strength in the body, on the rhythm of breath, on the feeling of contact with the floor—which directly alleviates the stress that comes from thoughts about the past or future. Anxious thoughts typically concern what might happen or what has already happened; present-moment awareness provides relief by anchoring attention in the only moment that actually exists.

Deepened relaxation: Mindful meditation during yoga can lead to deeper relaxation than physical practice alone, reducing stress hormone levels and allowing the nervous system to reset more completely. When the mind is fully engaged with present-moment experience, the rumination that maintains anxiety is interrupted, allowing for genuine rest.

Strength Training

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Strength training, also known as resistance training, involves using resistance to muscular contraction to build the strength, anaerobic endurance, and size of skeletal muscles. While traditionally associated primarily with physical goals like building muscle mass or improving athletic performance, strength training has increasingly been recognized as a powerful tool for mental health, including the management of anxiety. This type of exercise offers unique benefits that complement those of aerobic exercise, and may be preferred by individuals who find aerobic activities less appealing.

Benefits of Strength Training

Strength training can have a profound impact on both physical and mental health, making it a useful tool in the treatment and management of anxiety disorders. The mechanisms by which strength training reduces anxiety overlap partially with those of aerobic exercise but include some distinct elements related to the unique physiological demands of resistance work.

Strength training doesn't just change your body—it changes your brain. The confidence that comes from getting stronger, the focus required during heavy lifts, and the neurochemical changes from resistance exercise all contribute to reduced anxiety and improved mental resilience.

— Dr. Brett Gordon

Reduction of anxiety symptoms: Engaging in regular strength training can reduce symptoms of anxiety by decreasing overall muscle tension, enhancing mood through neurochemical changes, and improving sleep quality. Research specifically examining strength training for anxiety has found effect sizes comparable to those seen with aerobic exercise, suggesting that resistance training is a viable alternative for those who prefer it.

Hormonal benefits: Strength training increases the production of endorphins, the brain's feel-good neurotransmitters, and also influences testosterone and growth hormone levels in ways that can improve confidence and reduce anxiety. These hormonal effects occur in both men and women, though patterns differ somewhat between sexes.

Increased resilience: Regular strength training builds not only muscular strength but also mental resilience and self-efficacy—the belief in one's ability to handle challenges—making daily stressors easier to handle. The experience of progressively lifting heavier weights, of doing things that once seemed impossible, translates into greater confidence in other domains of life.

Improved body image: For many anxious individuals, concerns about physical appearance contribute to social anxiety and general distress. Strength training can improve body composition and, perhaps more importantly, shift focus from how the body looks to what the body can do, promoting a healthier relationship with physical self.

Simple Exercises

Here are some simple strength-training exercises that can be done at home to help manage anxiety, requiring minimal or no equipment and suitable for small spaces:

1. Squats

Purpose: Squats help in building leg muscles, particularly the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes, while improving core strength, contributing to overall stability, functional movement, and confidence in physical capability.

How to Do It: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and your arms straight out in front of you for balance, or clasped in prayer position at chest level. Begin by pushing your hips back as if sitting into a chair, then bend your knees to lower your body. Continue lowering until your thighs are parallel to the floor, or as far as comfortable while maintaining good form. Ensure your knees track over your toes without collapsing inward. Keep your chest up and back relatively straight throughout. Push through your heels to return to the starting position. Repeat for 10-15 repetitions, rest, and complete 2-3 sets.

2. Push-Ups

Purpose: Push-ups are excellent for strengthening the upper body, including chest, shoulders, and triceps, while simultaneously engaging the core for stability, providing a comprehensive upper-body challenge.

How to Do It: Begin in a plank position with your hands placed on the floor slightly wider than shoulder-width apart, arms straight, and body forming a straight line from head to heels. Lower your body by bending the elbows until your chest nearly touches the floor, keeping your core tight so your back doesn't sag and your hips don't pike up. Keep your elbows at about a 45-degree angle from your body rather than flared out to the sides. Push back up to the starting position. If full push-ups are too challenging, modify by keeping knees on the floor. Aim for as many repetitions as possible with good form, rest, and complete 2-3 sets.

3. Lunges

Purpose: Lunges develop leg and abdominal muscles while promoting functional movement patterns, enhancing balance and coordination, and building the strength needed for daily activities and athletic pursuits.

How to Do It: Stand with your feet together, hands on hips or at your sides. Take a controlled step forward with your right leg, lowering your hips toward the floor by bending both knees to approximately 90-degree angles. The back knee should come close to but not touch the ground. Your front knee should be directly over the ankle, not pushed forward past the toes, and your back knee should point straight down toward the floor. Push through the front heel to return to starting position. Repeat on the same leg for desired repetitions, or alternate legs. Complete 2-3 sets of 10-12 repetitions per leg.

Tai Chi and Qigong

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Tai Chi and Qigong are traditional Chinese exercises known for their slow, deliberate movements and deep breathing, making them particularly effective in reducing anxiety and promoting relaxation through gentle, meditative movement. These practices differ significantly from Western exercise modalities in their emphasis on internal experience, energy flow, and the cultivation of calm awareness, offering unique benefits for anxiety management.

Overview of Tai Chi and Qigong

Tai Chi originated as a martial art in China centuries ago but has evolved into a form of exercise that benefits both physical and mental health through gentle, flowing movements performed with focused attention. The practice involves sequences of movements that flow continuously from one to the next, performed slowly and with careful attention to body position, weight distribution, and breathing. Despite its martial origins, modern Tai Chi practice is typically non-competitive and focused on health and meditation rather than combat applications.

Qigong, which translates to "life energy cultivation" or "working with vital energy," is a holistic system of coordinated body posture, movement, breathing, and meditation used for health, spirituality, and martial arts training. Qigong practices range from simple exercises that can be learned in minutes to complex forms that take years to master, offering entry points for practitioners at all levels. The practice is based on traditional Chinese concepts of vital energy (Qi) flowing through the body, with exercises designed to promote smooth, balanced energy flow.

Both Tai Chi and Qigong are based on the principle of balancing and cultivating the Qi or vital energy within the body, which traditional Chinese medicine considers essential for maintaining health and harmony in all the body's systems. While modern science does not validate the concept of Qi as a literal substance, research does support the practices' effectiveness for reducing anxiety, improving balance, reducing pain, and enhancing overall well-being through mechanisms that can be explained in conventional physiological terms.

Core Movements

1. Tai Chi - Wave Hands Like Clouds

Purpose: This fundamental Tai Chi movement promotes relaxation through smooth, flowing motions that mimic the gentle movement of clouds across the sky, coordinating movement with breath in a meditative rhythm.

How to Do It: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, knees slightly bent, weight evenly distributed. Hold your arms up in front of your body, slightly rounded with elbows down and fingers pointing up, as if gently embracing a large ball. Shift your weight onto your right leg while slowly moving both hands to the right, the upper hand at face level and the lower hand at waist level. As hands pass the centerline, begin shifting weight to the left leg while the hands continue moving left. The movement is continuous, like slowly stirring a large pot, with the waist turning gently and the arms following. Continue for several minutes, coordinating movement with slow, natural breathing.

2. Qigong - Lifting The Sky

Purpose: This classic Qigong exercise stretches the body while guiding Qi flow from earth through the body toward the sky, promoting stress relief, opening the chest, and creating a sense of expansion and energy.

How to Do It: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, arms relaxed at your sides, eyes gently open or closed. Breathe in slowly as you raise your hands, palms facing up, in front of your body. Continue lifting until your hands are above your head, palms facing the sky, with a gentle stretch through the arms and sides of the body. Breathe out as you turn your palms outward and slowly press them down toward the ground, slightly bending forward at the waist. Feel as though you are gently pressing down through water or sand. Return to standing and repeat 8-12 times, synchronizing movement with breath.

Connection to Anxiety Reduction

Tai Chi and Qigong help manage anxiety through their meditative movements and focus on deep, rhythmic breathing, which are key in inducing a state of mental relaxation and physical calm. The slow, deliberate nature of the movements requires continuous attention, which naturally reduces the rumination and worry that characterize anxiety.

Mind-body connection: Both practices strongly enhance the connection between mind and body, requiring moment-to-moment awareness of position, movement, and sensation that helps distract from daily stressors and anchor attention in present experience. This cultivation of body awareness also helps practitioners notice early signs of tension and anxiety, enabling earlier intervention.

Reduced physical tension: The gentle, flowing movements increase flexibility and functional range of motion while reducing muscle tension and chronic pain, which are often associated with anxiety. The slow stretching and controlled movement help release holding patterns that develop in response to chronic stress.

Enhanced breath control: The emphasis on slow, deep, coordinated breathing directly activates the parasympathetic nervous system, increasing oxygen flow to tissues and triggering the body's natural relaxation response. Over time, the breathing patterns learned in practice can become habitual, reducing baseline anxiety.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR) is a systematic technique designed to help individuals reduce stress and anxiety by alternately tensing and then relaxing different muscle groups throughout the body. Developed by American physician Edmund Jacobson in the early twentieth century, PMR is based on the observation that mental calm and physical relaxation are closely linked—releasing muscular tension tends to release mental tension as well. The technique has been extensively researched and validated as an effective treatment for anxiety, insomnia, and stress-related conditions.

Technique Explanation

PMR involves deliberately tensing each muscle group in the body for a brief period, then suddenly releasing the tension and noticing the resulting sensation of relaxation. The tensing should be firm but never to the point of pain or cramping—the goal is to create enough tension to clearly feel the contrast when it is released. The focus throughout is on the contrast between tension and relaxation, which helps practitioners learn to identify and release the chronic muscle tension that often accompanies anxiety without their awareness.

The logic of PMR rests on several principles. First, many anxious individuals are so accustomed to muscle tension that they no longer notice it; by deliberately creating more tension, they can more easily feel when it releases. Second, muscle relaxation is physiologically incompatible with anxiety—deeply relaxed muscles send signals of safety to the brain that are difficult to override with worried thoughts. Third, the focused attention required during PMR provides a break from anxious rumination. Fourth, regular practice trains the ability to relax quickly and deeply, creating a skill that can be deployed in anxious moments.

Routine Walkthrough

Here is a step-by-step guide to a basic PMR session:

1. Find a Quiet Place and Comfortable Position: Lie down on your back in a comfortable spot, such as a bed, yoga mat, or carpeted floor. A pillow under your knees can reduce lower back strain. Alternatively, sit in a comfortable chair with back support. Close your eyes and take several slow, deep breaths to begin settling.

2. Feet and Legs:

- Tense: Curl your toes downward tightly and tense your foot muscles, feeling the tension throughout the foot. Hold for about 5 seconds.

- Relax: Quickly release all the tension in your foot. Feel the muscles become loose and limp. Notice the contrast between tension and relaxation—the warmth, heaviness, and ease in the muscles. Rest for 10-15 seconds, continuing to notice the relaxed sensations.

- Move up to the calves: tense by pointing toes upward toward shins, hold, then release.

- Continue to thighs: tense by pressing thighs together or pressing them into the surface beneath you, hold, then release.

- Buttocks: squeeze the muscles together, hold, then release.

3. Hands, Arms, and Shoulders:

- Tense: Make tight fists and tense all the muscles in your forearms. Hold for 5 seconds.

- Relax: Release the tension suddenly and completely. Feel the limpness and warmth in your hands and arms. Rest for 10-15 seconds.

- Upper arms: tense by bending elbows and tensing biceps, hold, then release.

- Shoulders: raise shoulders toward ears, creating tension, hold, then release and let shoulders drop.

4. Face and Neck:

- Tense: Squeeze your eyes shut, wrinkle your forehead, and clench your jaw to tense facial muscles. Hold for 5 seconds.

- Relax: Release all facial tension. Let your forehead smooth, jaw drop slightly open, and face become soft. Notice the relaxation spreading across your face. Rest for 10-15 seconds.

- Neck: gently press head back into pillow or headrest, hold, then release.

5. Chest, Stomach, and Back:

- Tense: Take a deep breath and hold it while tightening the muscles in your chest and stomach. Hold for 5 seconds.

- Relax: Exhale and let your chest and stomach become completely loose. Rest for 10-15 seconds.

- Back: arch your back slightly, pressing shoulder blades together, hold, then release and let your back sink into the surface beneath you.

6. Complete the Routine: Spend several minutes lying quietly with your eyes closed, breathing deeply and slowly. Mentally scan your body for any remaining areas of tension, and consciously release them. Enjoy the sensation of full-body relaxation. When ready to end the session, gradually begin to move fingers and toes, stretch gently, and open your eyes.

Effects on Anxiety

PMR is particularly effective for stress and anxiety relief due to several complementary mechanisms:

Mind-body connection: PMR dramatically enhances awareness of physical sensations, particularly the contrast between tension and relaxation, helping practitioners recognize and release the chronic muscular holding that accompanies and perpetuates anxiety. Many people are surprised to discover how much tension they were carrying without awareness.

Reduction in muscle tension: Since muscle tension is a common physical manifestation of anxiety—tense shoulders, clenched jaw, tight stomach—learning to recognize and release it directly addresses one of anxiety's most uncomfortable physical components. This release often produces immediate relief and a sense of calm.

Deep relaxation: The profound state of physical relaxation achieved through complete PMR practice activates the parasympathetic nervous system and can decrease everyday stress levels while reducing physiological symptoms of anxiety such as rapid heartbeat, shallow breathing, and muscle tension. Regular practice produces cumulative benefits, with baseline anxiety decreasing over time.

Sense of control: Learning PMR provides a concrete tool for managing anxiety—something practitioners can actively do when they feel anxious rather than feeling helpless. This sense of control itself reduces anxiety, as much of anxiety's distress comes from feeling unable to manage the experience.

Author: Amelia Hayes;

Source: psychology10.click

The relationship between physical exercise and anxiety relief represents one of the most robust findings in mental health research, offering hope and practical tools for the millions of people who struggle with anxiety disorders and subclinical anxiety symptoms. The various forms of exercise explored in this article—breathing exercises, aerobic activities, yoga, strength training, Tai Chi and Qigong, and progressive muscle relaxation—each offer unique pathways to anxiety reduction while sharing common mechanisms including neurochemical changes, autonomic nervous system regulation, and the cognitive benefits of present-moment focus.

The evidence is clear that regular physical activity can significantly reduce anxiety symptoms for most people, with effects comparable to medication and psychotherapy for many individuals. Unlike medication, exercise produces no problematic side effects and offers numerous additional benefits for physical health, cognitive function, sleep quality, and overall well-being. Unlike psychotherapy, exercise can be practiced independently once learned, requires no appointments, and costs little or nothing. This accessibility makes exercise a first-line intervention that can be recommended to virtually everyone struggling with anxiety.

The key to success lies in finding forms of exercise that are enjoyable, sustainable, and matched to individual preferences and circumstances. Someone who dreads running will likely not maintain a running practice long enough to benefit, while someone who loves the social aspects of group cycling classes may find cycling becomes a cherished part of their routine. The best exercise for anxiety is the one you will actually do consistently—whether that means daily walks in the park, three weekly strength training sessions, a morning yoga practice, or some combination of activities that keeps you moving regularly.

For those just beginning to use exercise for anxiety management, starting small and building gradually offers the best chance of establishing lasting habits. Even brief sessions—ten minutes of walking, five minutes of breathing exercises—can produce immediate mood benefits while building the foundation for longer practices. The goal is not perfection but consistency, not intensity but regularity. Over time, as exercise becomes habitual and its benefits become apparent, most people naturally increase their engagement, finding that what once required willpower becomes something they look forward to and miss when unable to do it.

This article provides general information about exercise for anxiety management and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you are experiencing significant anxiety symptoms, please consult with a qualified healthcare provider or mental health professional for personalized guidance. Some forms of exercise may not be appropriate for individuals with certain medical conditions—consult your physician before beginning any new exercise program.

Frequently Asked Questions

Related Stories

Read more

Read more

The content on psychology10.click is provided for general informational and inspirational purposes only. It is intended to share evidence-based insights and perspectives on psychology, relationships, emotions, and human behavior, and should not be considered professional psychological, medical, therapeutic, or counseling advice.

All information, articles, and materials presented on this website are for general educational purposes only. Individual experiences, emotional responses, mental health needs, and relationship dynamics may vary, and outcomes may differ from person to person.

Psychology10.click makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the content provided and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for decisions or actions taken based on the information presented on this website. Readers are encouraged to seek qualified professional support when dealing with personal mental health or relationship concerns.